But today there is no day or night,

Today there is no dark or light,

Today there is no black or white,

Only shades of gray.

My wife and I are avid accumulators. Our house is an interesting amalgam of pop culture pieces from our youth and antiquities that predate even our parents’ childhoods. Don’t expect to see us on Hoarders anytime soon. Our collections are displayed in an orderly fashion throughout our three-story residence. We do, however, have a collection of collections. One morning in the early 90s, my wife and I set out to browse the offerings of a collectibles show at a convention center in Valley Forge, PA, not far from our home.

The facility was bustling with dedicated collectors searching for that elusive piece or unusual knick-knack. Mrs. Pincus and I prowled the aisles of merchandise, anxious to spot that one cool item that all others had overlooked. Along with the opportunity to view the wares of hundreds of dealers, the show promoters booked an appearance by two celebrities whose presence would have nostalgic appeal to the attendees. It was here I began another collection this one of autographed celebrity photos. At a small folding table, covered with various glossy 8 x 10 photos, sat Butch Patrick. Butch played child werewolf Eddie on the 60s sitcom The Munsters. As a youngster, he also starred in the feature film The Phantom Tollbooth and, after the cancellation of The Munsters, he took on a handful of guest roles in episodic television. And then, he grew up. No longer a cute little kid, Butch had much difficulty finding acting work. He began showing up at fan conventions and collector shows, signing autographs and posing for pictures for a few bucks. He essentially made it a second career. I was intrigued at meeting Butch. After all, I had watched and enjoyed The Munsters as a kid and later in countless reruns. Butch was a nice guy and he chatted with my wife and me, as our young son sat in his stroller and played Game Boy, totally uninterested. I happily handed five bucks to Butch in exchange for a personalized black & white photo of him in full Eddie makeup. We talked more and it seemed as though he didn’t want us to leave. I looked around and, unfortunately, we were the only ones expressing any interest in meeting Butch Patrick. Just a few feet away was the ever-lengthening end of a long, snaking line of fans, excitedly awaiting their chance to meet the event’s other celebrity — Davy Jones. The Monkees, TV’s “Pre-Fab Four,” were enjoying a new-found popularity with a new generation (based on a recent re-introduction by cable television) and the Philadelphia-area contingency were out in full force. The convergence of recent and long-time admirers queuing up to spend a few brief minutes with the diminutive Mr. Jones was so long and so far from his “meet & greet” set-up, we couldn’t even get a fleeting glance of him. We knew he was in the building, but there may as well have been an ocean dividing us. We decided to finish perusing the remainder of the dealers’ tables and call it a day. Hopefully, I’d get the opportunity to cross paths with Davy again.

In 2006, my family attended the annual eBay Live convention where buyers and sellers, who frequent the internet’s largest auction website, interact and rejoice in all things eBay. (Mrs. Pincus has maintained the Mars Hotel eBay store for over 15 years.) This particular convention was held at the Mandalay Bay resort in Las Vegas. For three days, we ate, drank, slept, complained about, marveled at and discussed eBay. It was an interesting experience and the surreal atmosphere of Las Vegas was the perfect setting for the sometimes otherworldly crowd that eBay proudly boasts as its core community. The first evening featured a keynote speech by then-CEO Meg Whitman, who stopped short of waving pom-poms in the air and forming a human pyramid with other eBay staffers, as she sang the company’s praises with crowd-stirring enthusiasm somewhere between that of a high-school cheerleader and a gospel preacher. At the time, eBay was using The Monkees’ tune “Daydream Believer” in their TV commercials, focusing on the lyric “oh, what can it be,” as an anthropomorphic “IT” cavorted with happy and satisfied eBay customers. At the conclusion of Meg’s speech, the curtains behind her parted to reveal a full band, complete with go-go booted-back-up singers, on a moving platform advancing to the edge of the stage. While the band played the opening bars of the aforementioned Monkees’ classic, none other than Davy Jones himself appeared at the stage-front and belted out the familiar first verse. Suddenly, every woman over 45 and there were hundreds of them rushed to the stage and the orchestra pit became a sea of waving, vintage 1960s female hands. Davy happily leaned his tiny frame over the edge of the stage and pressed the girly palms of as many swooning 70s high-school graduates as he could. For the next forty-five minutes, Davy and the band plowed through hit after bubble-gum hit from the Monkees’ songbook. When the house lights finally flickered back on, the throng was ecstatic, entertained and most of all, sufficiently surprised by the impromptu performance. Especially, one Mrs. Pincus, whose hand was among those graced by a quick brush with Davy’s.

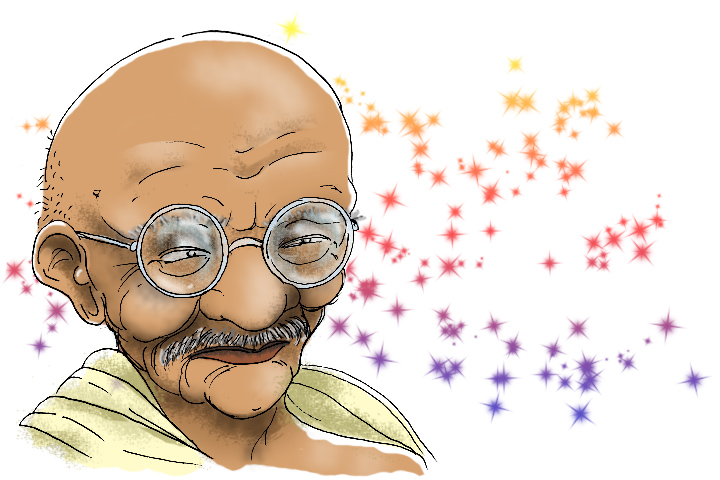

This past September, I drove down I-95 to a nondescript Marriott hotel in the Baltimore suburb of Hunt Valley. It was the site of the 6th Annual Mid-Atlantic Nostalgia Convention (MANC). In addition to the usual vendors hawking movie posters, long forgotten toys (still in their original packages) and poorly-duplicated, unathorized DVDs of films and TV programs that nevertheless elicit smiles, the MANC presented a diverse line-up of celebrity guests with an appeal to post-Atomic Age attendees. Seated behind long, photograph-laden, banquet tables were the likes of Oscar-winner Patty Duke, Room 222 cutie-pie Karen Valentine and her gruff co-star Michael Constantine, Father Knows Best TV siblings Billy Gray and Lauren Chapin and Leave It to Beaver big brother Tony Dow. A late addition to the roster and relegated to an outside hallway, away from the majority of his peers, was Davy Jones. When I arrived, the gray-tressed Davy was standing alongside a small folding table, wedged between a guy selling boxed bobble-head dolls and a fellow displaying cardboard crates crammed with theater lobby cards for movies no one has thought about for decades. He was scribbling on a torn sheet of paper, careful to avoid the small stacks of glossy photos covering the bulk of the table’s surface.

“Hey,” I spoke up to Davy, “What’re you doing?”

Davy stopped his writing, touched my shoulder, pointed to the page with his pen and answered me as though he were my best friend and we had spoken regularly. “I’m doing a concert for the Boys and Girls Club of Miami and I’m writing out a set list. I took the show over from Clarence Clemons (Bruce Springsteen’s longtime saxophone player who passed away in June 2011). I have to figure out what songs to do.” He turned his focus back to the paper, his Sharpie poised just above a recently deleted entry on his list.

I thought to myself: “Are you kidding me?!? Daydream Believer, I’m a Believer, that song you sang on The Brady Bunch and Hey! Hey! We’re The fucking Monkees! You’ve been singing these songs for 40 years, for crying out loud! You really think you need to write a set list?” Instead, I politely commented, “Oh.”

Davy asked if I’d like to purchase a photo and I selected a standard shot of the youngest Monkee in his signature double-breasted blue shirt shaking a pair of colorful maracas. As Davy inscribed the picture with an exaggerated flourish from his marker, I told him I was in the crowd at the eBay Live event in Las Vegas a little over five years earlier. He gently blew a drying breath towards the ink on the freshly-personalized picture and his eyes looked skyward while he searched his mind to corroborate my reference.

“Oh, right,” he began, “and they dropped green slime all over me while I sang! I remember!”

“What?,” I replied with inquisitive disbelief as I narrowed my eyes, “No. No. It was a concert at Mandalay Bay for eBay. You performed after the keynote speech.”

“Oh yeah,” he said and he pointed to the air in front of his nose. It was obvious that he had absolutely no idea what I was talking about. He added. “I thought you looked familiar.”

I cocked my head. “No, we didn’t meet. I was in the audience. You shook my wife’s hand. She was so happy. You nearly brought her to tears!”

“Why?,” Davy questioned, “Was I that bad?”

“No!,” I said, slightly raising my voice, “because you’re Davy Jones, for Christ’s sake!”

Davy had no reaction and not the slightest glimmer of recognition of the event. He graciously posed for a picture with me. I thanked him, expressed my pleasure of making his acquaintance and walked toward the inside room to meet the other celebrities.

Twenty or so minutes later, I had made the rounds, met the other celebrities, quickly examined wares of the other vendors and finally, exited the room in the direction of the hallway. I passed Davy and, again, he was hunched over his table, busily scribbling.

“How’s that set list going?,” I said as I strolled by Davy’s little table.

Davy looked up and gestured to the paper with his pen. “Yeah,” he began, “I’m doing this concert for the Boys and Girls Club of Miami that I took over for Clarence Clemons.”

“I know, Davy,” I answered, “We just had this conversation a few minutes ago.”

He stared back at me without expression and turned his attention back to his list. I turned my attention to the hotel’s parking lot and to locating my car.

Several weeks ago, I was listening to the radio at work. Between songs, the DJ announced that news came in reporting Davy Jones had suddenly passed away at age 66. He then segued into a Monkees song. As part of the generation that grew up watching The Monkees, I was genuinely saddened. As someone who had met Davy Jones a mere five months earlier, I was saddened a little more. However, as I reflected on the absurdity of our conversation, I smiled.

JPiC and Davy, September 24, 2011

Comments

comments