On a rainy Sunday morning, one week before Christmas, I visited three cemeteries in nearby Delaware County, just south of Philadelphia, in the shadow of Philadelphia International Airport. My first stop was tiny Mount Lawn Cemetery in Sharon Hill. Just down the street from the airport’s massive long-term parking lot, Mount Lawn is bisected by Hook Road, with the grounds seemingly split evenly. As I drove past the entrance, a heavy chain was stretched between two pylons. This obviously implied “We Are Closed” to any potential visitors. Disappointed, I parked my car on a side service road and thought about my next move. I decided to do something I would usually never do. I left my car and walked a muddy path along Hook Road to the chain-blocked entrance. Checking for any movement or signs of life in the large building that serves as an office, I simply walked around the pylon. The place was deserted. Actually, it looked abandoned. There were several sections that seemed under construction, piled with planks of wood, large mounds of dirt and cleared branches. However, it appeared as though work had ceased abruptly and workers hadn’t been there in some time.

Content that I would not be bothered in my grave quest, I proceeded down the surprisingly well-marked main road to the grave of the Hon. Lucien Blackwell.

Blackwell was a long time fixture in Philadelphia politics. From his beginning as a union leader, Blackwell worked his way through the ranks and was eventually elected to the United States House of Representatives. As a member of Philadelphia’s City Council, he was instrumental in passing legislation for the Pennsylvania Convention Center and breaking the long-standing code prohibiting city structures being built taller than City Hall. A mural reading “Thank you, Mr. Blackwell” can be seen in West Philadelphia.

On the far end of Mt. Lawn, in the center of sparsely populated Section C, is the grave of legendary blues singer Bessie Smith.

Nicknamed “The Empress of the Blues,” Bessie is regarded as one of the greatest singers of the 20s and 30s. She recorded over 160 songs and performed with top musicians of the day, including Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson and Chu Berry. She appeared in one film, St. Louis Blues, based on the W.C. Handy song. In September 1937, Bessie was traveling on desolate Highway 61 to Clarksdale, Mississippi, in a car being driven by her common-law husband, Richard Morgan. Richard misjudged the speed of a truck just ahead of him and hit the rear of the vehicle at top speed. Coincidentally, a surgeon passing by stopped at the accident scene and attempted to treat a severe wound to Bessie’s arm. After too much time and a great loss of blood, Bessie was transported to a “blacks only” hospital. Her right arm was amputated, but Bessie died the next morning, having never regained consciousnesses. Her funeral was attended by 10, 000 mourners before her body was buried at Mt. Lawn (outside of her adopted hometown of Philadelphia). The grave went unmarked for years until singer Janis Joplin purchased a headstone in 1970. Joplin died of a heroin overdose a few months later.

On the other side of the office, in an area filled with fallen leaves and bare hedges, is the plot of the Montgomery Family. This marks the grave of singer Tammi Terrell.

In her short career, Tammi scored seven Top 40 hits with her singing partner Marvin Gaye, including “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” and “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing.” During a concert in Virginia, Tammi collapsed into Gaye’s arms. Later diagnosed with a brain tumor, Tammi endured eight unsuccessful operations before she died in 1970 at age 24. She is buried under her real name Thomasina Montgomery.

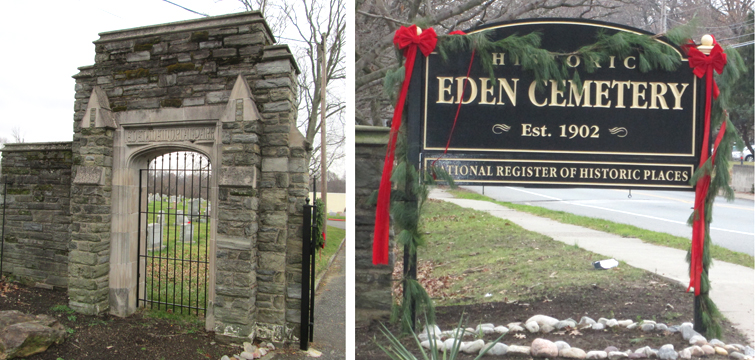

I kicked the mud out of the soles of my boots, hopped in my car, and started toward my next destination, Eden Cemetery. Placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010, Eden makes the claim of being the oldest African-American owned cemetery in the United States, but that is disputed. When the City of Philadelphia condemned a number of African-American cemeteries in the early 20th century, Eden was established in 1902 to re-inter the exhumed bodies. Many of the reburials took place at night in order to avoid the regular protests from prejudiced residents of the neighborhood.

Just inside the entrance gate is the grave of opera singer Marian Anderson.

In addition to being one of the most celebrated singers of the 20th century, Marian Anderson was an important figure in the fight for racial equality. Denied the right to perform at Washington’s Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution, Marian sought help from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and gave an outdoor concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday 1939. She continued to break barriers for her entire career, becoming the first African-American to perform at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

On a hill past Marian Anderson’s grave is the huge polished black marble stone that marks the plot of Rev. Dr. Charles Albert Tindley.

While his name my not be familiar, Reverend Tindley earned himself the nickname of “The Father of Gospel Music.” In his lifetime, he penned over sixty hymns, including “Stand by Me” (later interpolated by Ben E. King as a hit in the 50s and again in the 80s) and “I’ll Overcome Someday,” which was the basis of the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” The words and music to his composition “Beams of Heaven” are etched into his headstone.

Driving deeper into the paths of Eden Cemetery, I came across this unusual structure.

I made a phone call to the office and was told, by a very helpful woman named Iris, that this is a storage chamber for corpses awaiting burial. In the days before commercially refrigerated morgues, this natural vault dug into a hillside and secured with bricks and a heavy, lockable door was used to house bodies prior to interment, while the graves were still dug by hand. The vault is no longer used, but it looks like it got a recent coat of paint.

At the corner of the “Lebanon” section is the recently dedicated monument to Octavius Catto.

Catto was an educator and early civil rights activist, in addition to an advocate for baseball in Philadelphia after the Civil War. The strong and outspoken Catto was shot to death on Election Day 1871, during an altercation in which white voters were trying to stop black voters from casting their votes. Despite many witnesses, his murderer was never convicted.

I swung a U-turn on the narrow paved roadway and set out for my next stop… although this family had to stay. They had no choice.

Heading down Route 13, I found myself driving parallel to Holy Cross Cemetery. Taking up an enormous amount of land, Holy Cross, under the auspices of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia like its crosstown cousin Holy Sepulchre, is a beautifully maintained, densely populated cemetery. Once thorough the gates, I felt as though I had stumbled into a Jesus convention. Joseph and Mary’s Pride-and-Joy is well-represented, in some form, on nearly every single plot. There are full-size Saviors, arms raised in either devotion or declaration of a satisfactory field goal. There are small Jesuses, dwarfed by a towering counterpart several graves away. Crucified figures and those kneeling in eternal prayer are mixed among the busts, reliefs and other sub-deities, just along for the ride.

I was unsure about visiting on a Sunday, as I am more familiar with the customs of Jewish cemeteries. On Saturdays (the Jewish Sabbath), cemeteries are strictly off-limits, as are most things. It is a day of rest and rest you shall. Much to the contrary, Catholic cemeteries have no such rule. Sundays are as good as any for a trip to see how Grandma’s perpetual care is doing. As a matter of fact, I picked the best day to come. It was obviously “Decorate Your Loved One’s Grave for Christmas” Day. As I made my way through the narrow paths, I was constantly aware of the many cars strewn haphazardly about the grounds. Nearby each one was a multi-generational family weeding through great bundles of ribbon-wrapped fresh garland and boxes of glittery decorations. I passed a few graves that were already decked out in holiday regalia, the result of early risers.

The names on the majority of headstones and grave markers at Holy Cross read like the character list of a season of The Sopranos. Among its 84,000 interments, there is an overabundance of Annunziatos, Fioravantis, Malatestas, Castelluccios and other similar-sounding names. A few infamous names are represented, like Michael Maggio.

Maggio was an old-school boss in Philadelphia’s organized crime. Besides being connected to some pretty good ricotta and other cheese products, Maggio was responsible for introducing and mentoring Angelo Bruno into the ways of The Mob.

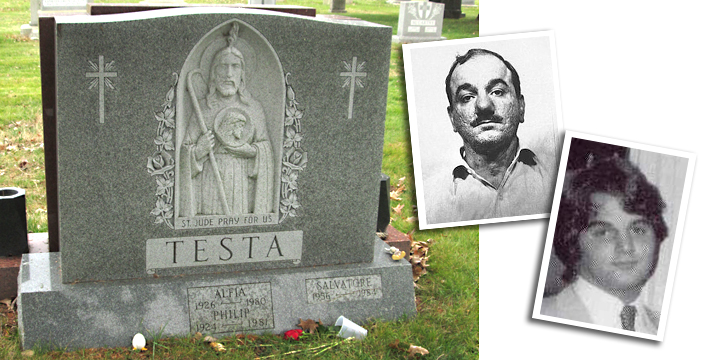

Bruno, buried just a short distance from Maggio, ran the Philadelphia crime family for twenty years. His preference for non-violent compromise earned him the nickname “The Gentle Don.” However, in 1980, he met an anything-but-gentle end, when he was killed by a shotgun blast to the back of his head while he sat in his car. Upon his death, Bruno was replaced by Philip “Chicken Man” Testa.

Testa, whose grave sits one section over from his former Don, was immortalized in the opening line of Bruce Springsteen’s song “Atlantic City” (Well, they blew up the Chicken Man in Philly last night/ And they blew up his house, too). Testa, in power for just one year, was killed when a nail bomb exploded under his porch when he turned the key in his front door. Phil’s son Salvatore, himself a rising figure in organized crime, was murdered by subsequent Philadelphia boss Nicky Scarfo in 1984. Scarfo was Salvatore’s godfather. Salvatore is buried with his father.

Speaking of murder, Holy Cross is also home to the unmarked grave of one of the first documented serial killers in the United States, Herman Mudgett better known by his alias of Dr. Henry Howard Holmes.

Holmes, whose exploits were chronicled in the book The Devil in The White City, opened a supposed hotel during the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. The hotel, dubbed “The Castle” by the surrounding neighborhood, was actually an elaborate torture and murder site. He was arrested and convicted for four murders, but authorities believe that actual number is closer to 400. He was executed at Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia (the current location of a supermarket). Perhaps these two unfortunate monuments are the handiwork of Holmes’ spirit. In 2017, Holmes’ descendants had his secret grave opened up to determine if the remains were, indeed, that of their relative. There were rumors that Holmes, although hanged in prison, had faked his death. Jeff Mudgett, Holmes’ great-great-grandson also believes that his relative was another notorious murderer — Jack the Ripper. Due to Holmes’ coffin being contained in concrete, his body was found not to have decomposed normally. His clothes were almost perfectly preserved. The body was positively identified as Holmes. Holmes was then reinterred. It should be noted that Jeff Mudgett currently co-hosts a show on The History Channel about H.H. Holmes’ crimes.

Switching gears, I located the grave of Frank Hardart Sr.

Hardart, along with his business partner Joseph Horn, opened a tiny luncheonette on South 13th Street in Philadelphia. Their French-drip coffee, a Southern favorite, was unique to the area and word of mouth brought in non-stop business. Soon, the pair opened the first Automat in the United States. It was based on a similar concept popularized in Germany. The Automat featured prepared foods behind small glass windows and coin-operated slots. Cashiers, known as “nickel throwers,” dispensed coins for customers. A full, but simple, meal could be purchased for under a dollar. Using the slogan “Less Work for Mother,” the company also pioneered easily-served “take-out” food. Horn & Hardart’s Automats remained popular for nearly a century. At one point, they operated over 150 restaurants in Philadelphia and New York, until the rise of fast-food chains brought a gradual end to their empire. The company closed its last Automat in 1991. (Joseph Horn is buried at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery.)

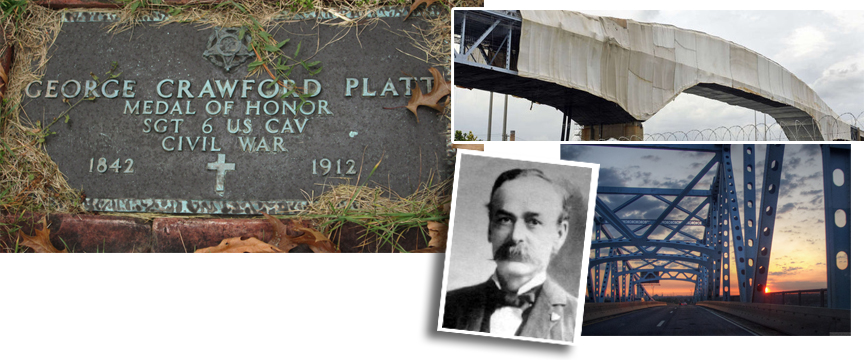

Just a few sections up from Hardart’s plot is the curbside grave of George C. Platt.

Sergeant Platt was the recipient of the Medal of Honor for bravery during the Civil War. Philadelphia chose to honor his accomplishment by naming a bridge that is constantly under construction after him.

Holy Cross also has its share of unusual grave monuments, including these two:

The Iannelli plot (on the left) features a full-uniformed firefighter* flanked by to saintly-looking characters and a cherubic baby for good measure. The DeFeo grave shows a distraught young lady weeping at the well-dressed, three-dimensional feet of — I can only assume — the late Mr. DeFeo. Mr. DeFeo looks as though he is about to write a long overdue letter. I’ll bet it’s really long overdue.

(A reader set me straight and correctly identified the uniform on the figure on the Iannelli memorial. It is a WWI uniform, not a firefighter.)

My quest over, I was looking for the nearest exit route (there are many gates), when I spotted something in my peripheral vision. I drove slowly and spied a small fox dodging in and out of the headstones.

He tried to convince me of a better life at Pleasure Island but I turned him down and quickly drove off.

I stopped for a pizza…

… and headed home.

* * * * *