For years, I have passed by Philadelphia’s iconic City Hall and marveled at its façade. The building sits at the crossroads of Market Street and Broad Street, smack in the center of the busy commerce of the City of Brotherly Love. It took 30 years to build and is embellished with 250 statues created by Scottish sculptor Alexander Milne Calder, including a 37-foot tall bronze statute of William Penn, the tallest statue atop any building in the world. City Hall, although derided by Philadelphians upon its completion, has become a beloved part of the city, not to mention its distinction as the world’s largest free standing masonry building. With nearly 700 rooms, it is also the largest municipal building in the world.

In addition to the sculptures that adorn the building columns, windows and walls, the walkways around City Hall boasts a number of statues. On the east side of the building, keeping careful watch over the Dunkin Donuts across the street, is a dapper, larger-than-life size statue of noted local businessman John Wanamaker. One year after his death, schoolchildren donated $50,000 in pennies to help finance the creation of the statue and eventual installation in 1923. I have passed this statue a zillion times and have always been intrigued by the inscription on its granite base… considering John Wanamaker’s contributions to Philadelphia. He opened one of the first department stores in the country. An innovative businessman, he created and popularized the money-back guarantee, a fixed-price system, and other consumer benefits that became industry standards. Wanamaker’s store was an opulent, 12-story showplace with a beautiful marble Grand Court which features the largest functioning pipe organ in the world. Wanamaker co-founded a homeless shelter and soup kitchen. He commissioned artwork and donated antiques to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. John Wanamaker also served as Postmaster General in the Benjamin Harrison administration. With all of those accomplishments, the inscription on the base of the Wanamaker statue identifies the subject as simply: “John Wanamaker, Citizen.”

In addition to the sculptures that adorn the building columns, windows and walls, the walkways around City Hall boasts a number of statues. On the east side of the building, keeping careful watch over the Dunkin Donuts across the street, is a dapper, larger-than-life size statue of noted local businessman John Wanamaker. One year after his death, schoolchildren donated $50,000 in pennies to help finance the creation of the statue and eventual installation in 1923. I have passed this statue a zillion times and have always been intrigued by the inscription on its granite base… considering John Wanamaker’s contributions to Philadelphia. He opened one of the first department stores in the country. An innovative businessman, he created and popularized the money-back guarantee, a fixed-price system, and other consumer benefits that became industry standards. Wanamaker’s store was an opulent, 12-story showplace with a beautiful marble Grand Court which features the largest functioning pipe organ in the world. Wanamaker co-founded a homeless shelter and soup kitchen. He commissioned artwork and donated antiques to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. John Wanamaker also served as Postmaster General in the Benjamin Harrison administration. With all of those accomplishments, the inscription on the base of the Wanamaker statue identifies the subject as simply: “John Wanamaker, Citizen.”

One day, on our drive back to the suburbs from our son’s South Philadelphia home, my wife and I were stopped at a red light in front of City Hall. I glanced out the window at the familiar statue of John Wanamaker — silently observing the folks passing by, his hat and coat folded neatly in his right hand, while his left hand rests just inside the hip pocket of his patinaed trousers. A thought popped into my head. I have been visiting cemeteries for over a decade, including many in the Philadelphia area. “I wonder where John Wanamaker is buried?,” I wondered aloud. “You got the internet on your phone.,” Mrs. Pincus reminded me, “Look it up.”

So I did.

Findagrave.com, my go-to source for all things cemetery-related, told me that John Wanamaker is interred in the small graveyard at St. James the Less Church on West Clearfield Street, right here in Philadelphia. Well, actually, I wasn’t quite sure where “here” was. I had to check a map since I was unfamiliar with exactly where Clearfield Street ran. I located it on a map and discovered that it was in the neighborhood of another cemetery — the renowned Laurel Hill. I had been to (and chronicled) Laurel Hill several years ago, but Mrs. P and I, coincidentally, were going to a craft fair held at Laurel Hill in a week or so. Plans were made to stop by St. James the Less Church afterwards.

On a Saturday afternoon, my wife found herself navigating our car down West Clearfield Street — a narrow, pot-holed thoroughfare that cuts through a densely-populated North Philadelphia neighborhood. We parked along the high brick wall that envelops St. James the Less Church and its adjacent cemetery. (St. James is an interesting character. He is barely identified in the New Testament, confusingly referred to as both “Jesus’s brother” and “Jesus’s cousin.” He is the patron saint of apothecaries because he is often depicted carrying a club…. and druggists work with a small club-like object. Get it?) We entered past a set of opened, wrought-iron gate that revealed a beautiful path paved with thousands of nearly-identical golden bricks, reminiscent of the route Dorothy Gale took through Oz. I scanned the grounds, hopeful to spot a grave marker inscribed with the Wanamaker family name. My wife gestured towards the church building in the center of the property. There were a number of men, women and children milling about — all dressed in suits and dresses. Obviously, a funeral had taken place earlier and the remaining family members were now congregating around a buffet table. Folks chatted while holding paper cups and small plates. A long, black-draped table was manned by a bored-looking fellow who appeared to have not been told by his employer that today’s assignment was taking place in a cemetery. Nevertheless, I was on a quest and I wasn’t really certain what I was looking for.

According to Findagrave.com, John Wanamaker’s remains are in the Wanamaker Family Chapel. I looked around and saw a large stone structure with windows and wrought iron gates. However, there were no identifying plaques or markers or anything. And no mention anywhere of the name “Wanamaker.” We weren’t sure if this was the correct building. The only other building were the church itself and a small residence up near the entrance gate. We wandered about for a bit, as the funeral party was beginning to break up. Mrs. Pincus whispered to me her plans to snag a sandwich wrap from the remaining selection on the buffet table. I laughed, although I wasn’t sure if she was serious. But her plans were dashed when a woman spoke briefly with the table attendant, then gathered a tray of the remaining food, carefully carrying it in the direction of the street. Suddenly she stopped and handed it off to a smiling young man in a religious frock — notched collar and all. When she walked away, my wife approached him and spoke right up.

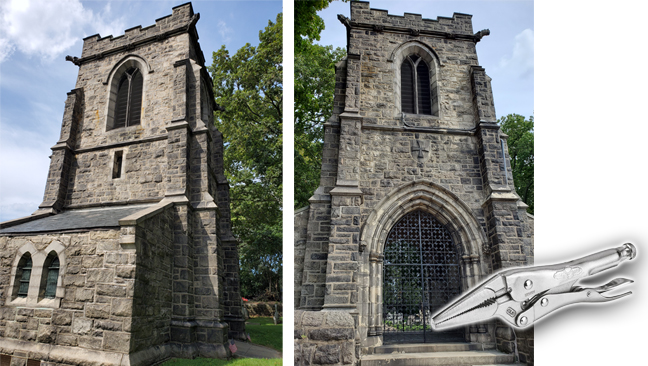

“Is that the Wanamaker Chapel?,” she asked, pointing in the direction of the building in the graveyard. The man, who introduced himself as “Father Andrew,” confirmed that is was indeed the Wanamaker Chapel. Mrs. P continued, “We weren’t sure. You see, we like to visit the graves of historical figures.” Father Andrew smiled even more broadly. “If you have a moment,” he offered, “I can take you inside.” He gestured the tray of sandwiches. “Let me put this away and I’ll meet you down there.” True to his word, he returned and we all walked a path to the chapel. As we walked, he told us of other notable names that are buried at St. James as well. When we got the the gates, Father Andrew merely undid the lock and swung the door open. The door to the crypt was a bit trickier. He reached into a hidden pocket in his robe and produced a Vice Grip pliers, explaining that workmen recently broke the key off in the lock. He fumbled for a bit, then finally swung the door in a cloud of dust.

Father Andrew revealed that Thomas Wanamaker, John’s son, passed away suddenly on a return trip from Egypt in 1908 at the age of 46. John, a devout Presbyterian, was distraught. He commissioned a chapel (actually just a large stone building with a belfry) to be constructed in which Thomas’ remains would be interred. The church soon insisted that the “chapel” be used as a family crypt, y’know…. as long as it’s here. Upon his death in 1922, John Wanamaker was interred here and six years later, son Rodman joined his family. Although an estimated 100 million dollars was divided among John Wanamaker’s surviving children and grandchildren, Rodman inherited the business and ran the family retail stores until 1928. Rodman, an avid golfer, founded the PGA and the Wanamaker Trophy is awarded for championships. We felt very honored and humbled, as not many people get to view the Wanamaker Family Crypt this closely.

As we made our way through the cemetery, Father Andrew pointed out the grave of Agnes Irwin.

The daughter of a US congressman and the great-great-granddaughter of Benjamin Franklin, Agnes served as the principal of Philadelphia’s West Penn Square Seminary for Young Ladies and later, the first dean of Radcliffe College. The West Penn Square Seminary for Young Ladies was renamed The Agnes Irwin School in her honor.

I thought that Father Andrew was going to point out the graves of Civil War soldiers as mentioned on Findagrave.com, but he showed us to more interesting interments. But first, he made sure we saw the lychgate near the entrance.

He explained that the lychgate was used for storing a body just prior to burial. The structure is gated on both sides and large, imposing lengths of chain hang from inside the rafters. In the early days of burials, a guard was posted here all night, behind the securely locked gates, to keep watch over the body and deter graverobbers.

We followed Father Andrew to the grave of Robert Hare.

Robert Hare was a respected chemist. Early in his career, he developed a blowpipe used in various applications for lab work. He was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania between 1810 and 1812 and again between 1818 and 1847. In the 1820s, he invented a “galvanic deflagrator,” a type of battery used for producing rapid and powerful combustion. But, in the 1850s, much to the chagrin of his colleagues and other students of science, he became interested in spirit mediums and the supernatural. He converted to Spiritualism. He experimented with moving tables, message communicators and other equipment employed by mediums. He was heavily criticized by fellow scientists, citing his subject’s propensity for committing fraud. However, Professor Hare was granted a US patent on a device that allowed communication with the spirit world. He asked the Presbyterian church to subsidize further research. They politely declined, but they did allow him to be buried in their churchyard upon his death in 1858.

Just across from Hare’s plot is the slab crypt of Henry Jones.

Henry Jones was a prominent caterer in Philadelphia. He was one of several African-American men who had excelled in the profession and garnered respect from Philadelphia’s upper class. He catered weddings and parties for dignitaries, earning a good living, eventually purchasing a beautiful home in the city. Through one of his regular white clients, Henry and his wife made funeral arrangements with Mount Moriah Cemetery (in Southwest Philadelphia) for their burial when their time came. Henry passed away on September 24, 1875. The morning of his funeral, Henry’s procession was stopped at the gates of Mount Moriah and denied entry. His frantic widow argued, but was told that they would not bury a black man in their cemetery. His body was transported to Lebanon Cemetery (now defunct) in South Philadelphia, when it remained in a holding vault for nearly a year. In April 1876, Henry’s widow purchased a plot at St. James the Less for $250, making it the first interracial cemetery in the city.

Father Andrew went on to tell us about the educational program St. James the Less provides for the surrounding community — a community that would otherwise be pushed to the wayside by the “selective” system in the city… “selective” in the same manner as Mount Moriah.

We thanked Father Andrew for his hospitality above and beyond the call and made our way back to our car.

* * * * *