I broke my own rule. When I started this little hobby of mine, I promised myself that one visit to a particular cemetery was enough. If could couldn’t locate every grave I set out to find well…. tough. I should have just looked harder. So, I’d go to a cemetery, find the graves, take the pictures and blog about them later. Sometimes I’d be disappointed when I couldn’t find that one specific plot (even after searching and searching), but, life is full of disappointments…. and here I am in a graveyard. But, today I went back on my promise to myself. I found myself headed to Philadelphia’s esteemed Main Line for a second visit to West Laurel Hill Cemetery. Twelve years ago, I took a hand-drawn map and a poor sense of direction on a freezing December morning to see who I could find at West Laurel Hill. Sure, I located the final resting places of some famous and not-so-famous folk, but I came away with the majority of names on my scribbled list unchecked. Now, over a decade later – and with help from a (not always reliable) GPS navigation, West Laurel Hill is like a brand new experience. There have been some prominent celebrity passings since my last visit, but I also found some celebrated names of those who died early in the previous century.

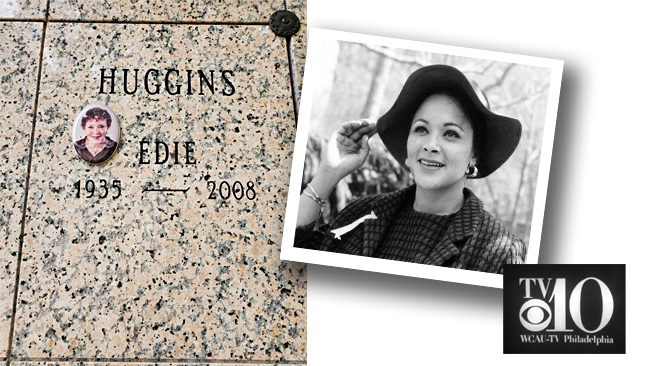

The field of news and news reporting is well represented at West Laurel Hill. As a matter of fact, the first grave I found was just inside the gates at the Mausoleum Of Peace. Just above eye level was the niche of Edie Huggins.

In 1966, Edie Huggins joined Philadelphia’s WCAU -TV and remained a beloved fixture at the station for 42 years. She was one of the first African-American women reporters in Philadelphia. Over the course of her lengthy career he served as a news reporter and journalist. She had the longest consecutive run of any television reporter in Philadelphia history.

Another TV news pioneer buried here is Dave Garroway.

Dave was the jovial host of NBC’s Today Show when it premiered in 1952. His easy-going demeanor was a hit with home audiences, as were his antics with simian co-host J. Fred Muggs. His sign-off of “Peace” accompanied by his open palm to the camera became his trademark. However, his friendly and comforting on-air persona hid his lifelong battle with depression and Dave took his own life by self-inflicted gunshot in 1982.

This massive cement headstone marks the grave of Cyrus Curtis.

Cyrus Curtis was a well-known publisher, famously publishing Ladies Home Journal and The Saturday Evening Post. He also published several newspapers, including The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Philadelphia Ledger and The New York Post. After his death, his estate in Wyncote, Pennsylvania (not too far from my home) was demolished and Curtis Arboretum was built on the grounds by his daughter.

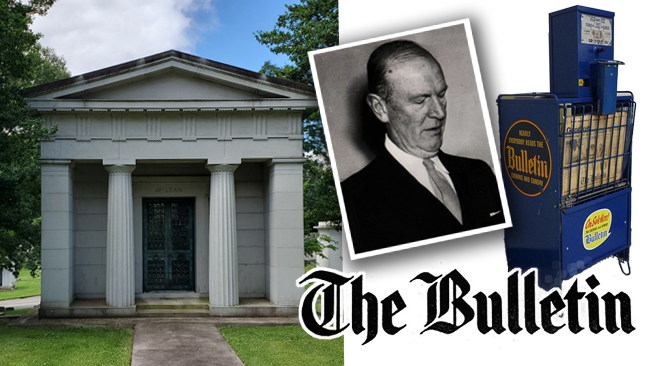

Robert McLean is interred in this stately mausoleum.

Robert McLean was the long-time publisher of Cyrus Curtis’ rival newspaper The Evening Bulletin. He also served as the President of the Associated Press for nearly 20 years.

There are many names from the world of industry at West Laurel Hill, including some inventors and innovators in their respective fields. William Breyer’s mausoleum stands at the end of the “Memorial” section.

In 1866, William Breyer produced and sold ice cream on the streets of Philadelphia. After he died of smallpox in 1882, his son incorporated the business and it grew to become one of the largest ice cream companies in the country. It has been sold several times over the years and is currently owned and distributed by the conglomerate Unilever. Unfortunately, the brand that once prided itself as being made from all natural ingredients, does not contain enough milk to be called “ice cream” and must legally be labeled “frozen dairy dessert.”

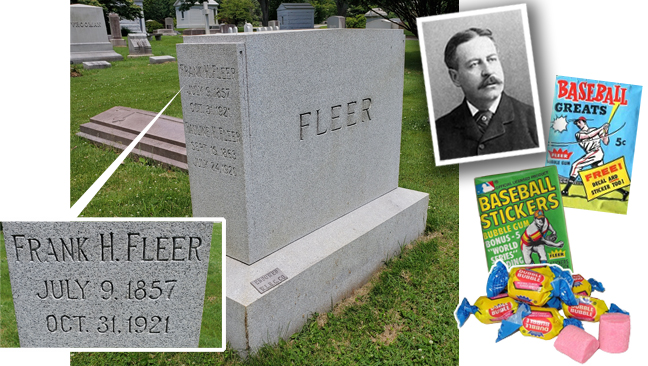

Nearby Breyer’s mausoleum is the grave of Frank Fleer.

Frank Fleer founded the Frank Fleer Corporation, where he developed a product called “Blibber-Blubber,” widely recognized as the first bubble gum. The product, however, was never marketed to the public. A Fleer employee, Walter Diemer, improved on the idea and, seven years after the founder’s death, Dubble Bubble was introduced. It was an instant hit with the public. The Fleer Corporation were also innovators in the production of trading cards, producing baseball cards for the first time in 1923.

Edward Budd Sr. and Jr. are side-by-side here at West Laurel Hill.

The Budd Corporation, founded in Philadelphia in 1912, was a major supplier to the automobile industry, fabricating the first all-steel automobile bodies. They also manufactured stainless steel passenger rail cars, including the famous California Zephyr. The technique of “shotwelding” was invented at Budd and it revolutionized the metal-working industry.

Eldridge R. Johnson calls this mausoleum his eternal home.

Eldridge Johnson, an engineer by trade, developed a motor to run the previously-hand cranked Gramophone. His new invention was the building block for his company – The Victor Talking Machine Company. He branched out, experimenting with recording and disc duplication. His venture eventually became the largest phonograph manufacturer in the world.

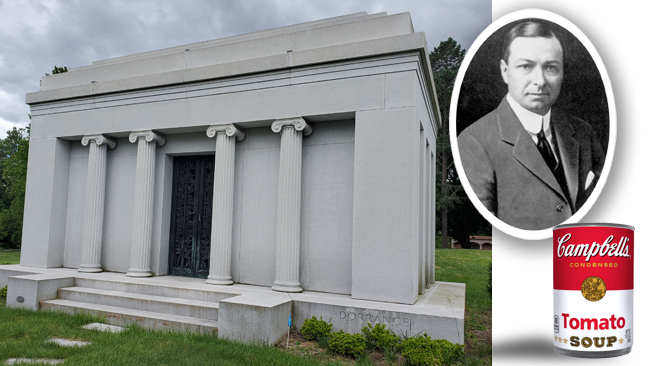

At the top of a hill is the mausoleum of the Dorrance family.

With a Bachelor of Science degree from MIT, John Thompson Dorrance worked as a chemist at the Campbell’s Soup Company in Camden, New Jersey. His uncle, Arthur Dorrance was general manager at Campbell’s and was reluctant to hire his young nephew. While earning a weekly salary of just $7.50, John developed a method of creating condensed soup, which became Campbell’s most commercially successful product. John was named president of the company in 1914 and served in that capacity until 1930 – when he bought out the Campbell family’s interest.

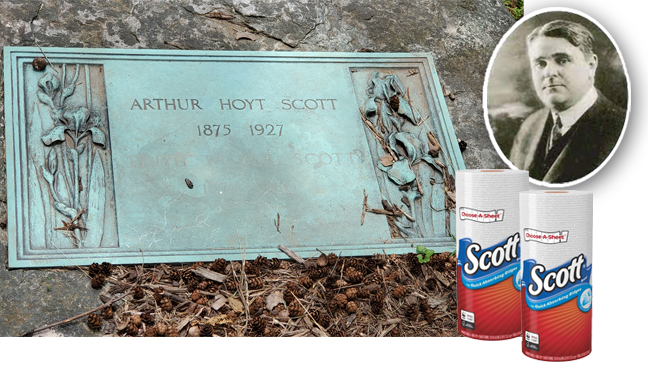

At the very top of another, rather steep hill, is the grave of Arthur Hoyt Scott.

Arthur, the president of the Scott Paper Company, was frustrated over a shipment of paper that was too thick to be used for the company’s chief product – toilet paper. He decided to cut the paper into sheets and sell it to hospitals, hotels and restaurants as disposable towels. It took some time, but eventually Arthur’s “paper towels” caught on with the public.

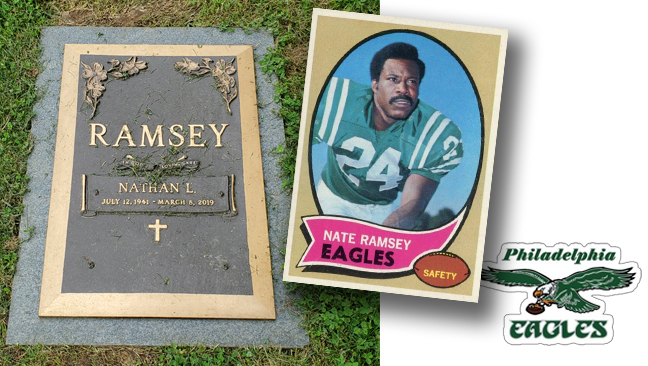

Two names from Philadelphia sports call West Laurel Hill home. Nate Ramsey is buried on the lawn in front of the Laurel Hill chapel.

A native of Neptune, New Jersey, Nate was a safety and defensive back for 11 seasons in the NFL. He played for the Philadelphia Eagles from 1963 until 1972. He spent the final year of his career with the New Orleans Saints.

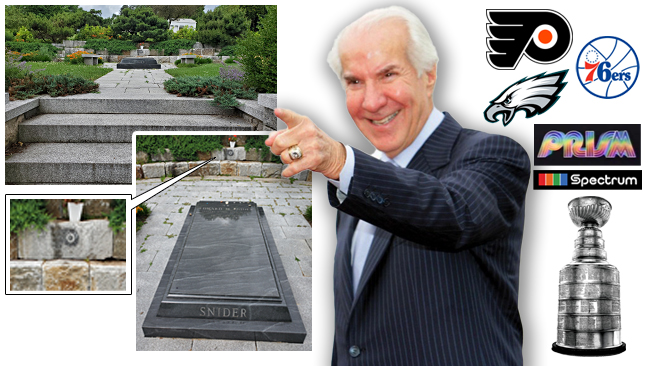

In this elaborate stone courtyard is the grave of Ed Snider.

A minority-stake owner of the Philadelphia Eagles, Ed and business partner Jerry Wolman made plans for a new arena in South Philadelphia to house the 76ers and the NHL’s new expansion team – The Philadelphia Flyers. The pair was awarded ownership of the new franchise and they built the Spectrum for the team. His Flyers brought the Stanley Cup to Philadelphia twice. Ed was instrumental in the establishment of PRISM, a local cable network, as well as WIP Radio’s change to an all-sports format. In 1996, he privately financed the building of a new arena, the Core States Center (Now called The Wells Fargo Center). In a 1999 Philadelphia Daily News poll, Ed was selected as the city’s greatest sports mover and shaker.

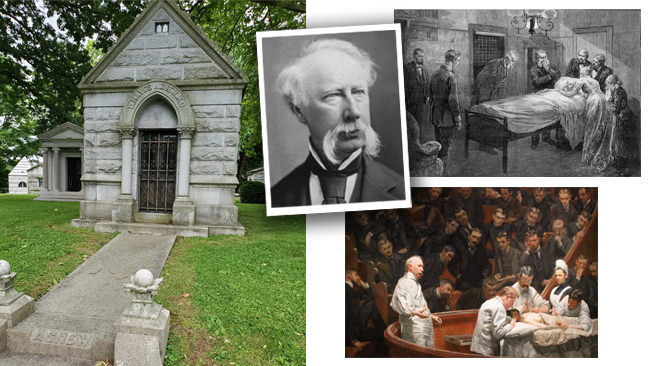

From sports to medicine and the rustic-looking mausoleum of Dr. D. Hayes Agnew.

A practicing surgeon, Dr. Agnew gained experience and reputation as an expert on gunshot wounds when he was consulting surgeon at a hospital outside Philadelphia during the Civil War. He was a professor and lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania, speaking predominately about human anatomy. In 1881, he was the chief consulting surgeon tending to President Garfield after he was shot. In the days follow the shooting, Dr. Agnew was never optimistic regarding the President’s prognosis. He is depicted in Thomas Eakins’ painting The Agnew Clinic, as well as in an illustration from Harper’s Weekly entitled The Deathbed of President Garfield.

The Humanities are also represented, including names from history as well as more recent contributors to the field. Across from Ed Snider’s grave is the ornate marker of Horace Trumbauer.

Horace was a prominent (and busy) architect. He designed many buildings in the Philadelphia area and across the country. He designed the Free Library of Philadelphia building. He also collaborated on the Philadelphia Art Museum. A lot of his designs were for private commissions, including the Elkins Estate and Lynnewood Hall, as well as commercial structures like train stations and hotels. His work was criticized in his time, but Horace has come to be appreciated and praised as one of the great American architects.

Members of the artistic Calder Family are buried beneath this stylized Celtic cross.

Alexander Milne Calder was a sculptor. He created over 250 marble and bronze figures that adorn Philadelphia’s City Hall. He also created the 37-foot tall statue of William Penn that stands on the building’s clock tower. It is the largest statue atop any building in the world. Alexander’s son, Alexander Stirling Calder, is best known for his Swann Memorial Fountain on Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway and for George Washington as President on the Washington Square Arch in New York City.

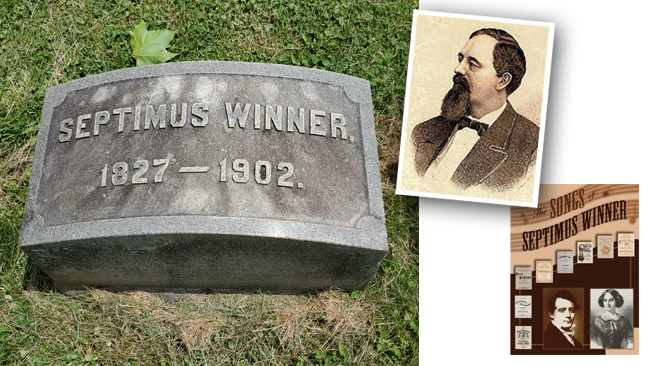

This unassuming headstone marks the grave of Septimus Winner.

Although his name may not be familiar, his songs sure are. Septimus Winner wrote hundreds of songs in the late 1800s, including Where Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone?, Ten Little Indians, Listen to The Mocking Bird, Whispering Hope, Carry Me Back to Tennessee and many more. In 1875, Septimus wrote The Spelling Bee, which, years later, showed up in a 1938 Three Stooges short re-titled Swinging the Alphabet.

Richie Barrett is buried under this large marker.

Richie was a songwriter and producer who, over the course of his career, worked with Little Anthony and the Imperials, The Chantels, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes and The Three Degrees. Richie managed The Three Degrees for over 20 years and produced their most successful albums.

In the center of West Laurel Hill is the Franconia section, forever home to Billy Paul, Teddy Pendergrass and Grover Washington Jr.

Billy Paul was a Grammy-winning singer, best remembered for his 1972 hit song Me and Mrs. Jones. Born Paul Williams, he changed his name to avoid confusion with the famous songwriter. He released 16 albums and was a vocal supporter of the civil right movement. Questlove, of The Roots, called Billy “one of the criminally unmentioned proprietors of socially conscious post-revolution ’60s civil rights music.”

Teddy Pendergrass began his career with Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, singing lead on their most popular hits like The Love I Lost, Wake Up Everybody and Bad Luck. He left the group in 1975 to begin a solo career. Teddy was wildly successful, prompting the media to refer to him as “The Black Elvis,” alluding to his crossover success. In 1982, he was involved in a car accident that left him paralyzed from the chest down. He continued to record albums, but found his popularity had diminished. Out of the spotlight for several years, Teddy made an emotional appearance at the Live Aid concert in Philadelphia in 1985. He performed sporadically and announced his retirement in 2006. He passed away in 2010 from colon cancer.

Grover Washington Jr. was a musician, arranger and producer. He collaborated with a number of artists and pioneered the “Smooth Jazz” genre. Following a performance on a network news magazine program, Grover collapsed backstage. He was taken to a hospital, where it was determined that he had suffered a fatal heart attack.

In between seeking out the “famous” graves, I spotted some unusual sights. The small Konidaris family mausoleum caught my eye.

Mr. and Mrs. Konidaris’ likeness are immortalized in stained glass and the noonday sun shining though it gave me a start when I saw it in my peripheral vision.

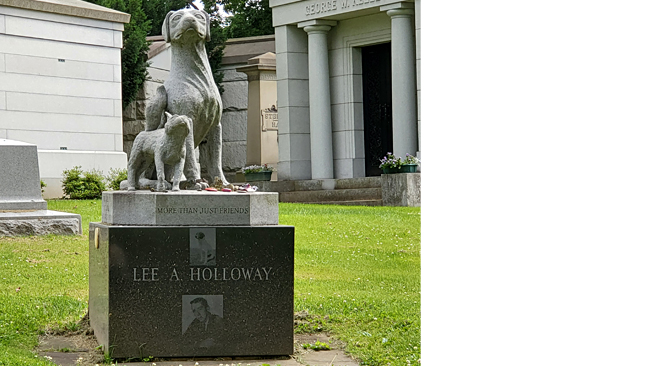

Lee Holloway wanted to be remembered as a friend to all – especially his four-legged companions.

These cement pets are captioned “More That Just Friends.” While West Laurel Hill does have a pet section, this grave is not in it.

At one point, I parked to check my location and I saw this massive monument with, what appeared to be a large palm tree branch laying across it.

Upon closer inspection, the branch is made of bronze, with a blue-green patina. Pretty cool.

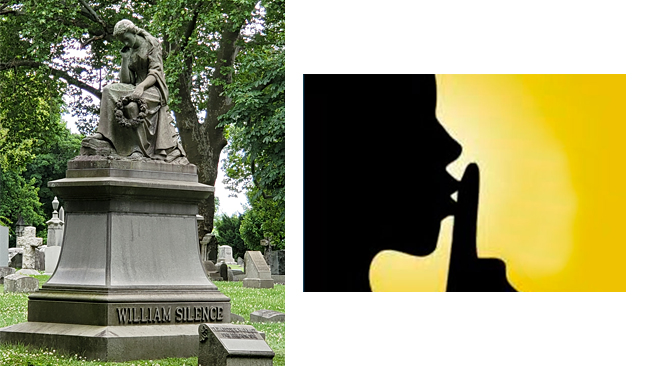

On my way out, I saw this family marker and knew I had nothing more to say.

* * * * *