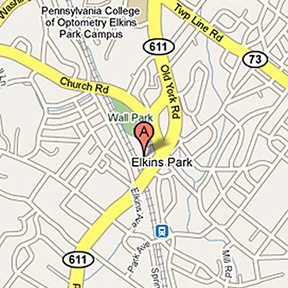

I have lived in Elkins Park for over thirty years. It is a small, unassuming little area just north of the bustling metropolis of Philadelphia, the

I have lived in Elkins Park for over thirty years. It is a small, unassuming little area just north of the bustling metropolis of Philadelphia, the fifth sixth largest city in the United States*. In those thirty years, I have only come to know a handful of my neighbors. I like to be a good neighbor by keeping my lawn cut, my trash cans orderly, my sidewalk shoveled in winter and my home in good repair. I expect my neighbors to do the same… and most do. I don’t appreciate when a neighbor’s trash blows into my yard or when some inconsiderate jerk parks in front of my house. leaving their rear bumper a foot or so into my driveway. For the most part, my neighbors (the ones I know and some that I don’t know) have been quite “neighborly,” with only a few exceptions.

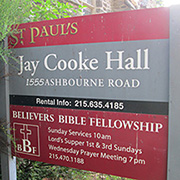

Just this morning, I met some of my quieter neighbors. I have driven past these folks for nearly three decades. They are the residents of Saint Paul’s Episcopal Churchyard and they silently reside just a few blocks from my house. If I wasn’t so lazy, I could actually walk there. But I didn’t. I drove my car and parked, ironically, at the synagogue parking lot across the street.

Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church is a typical neighborhood church with an active congregation that still holds services in the historically-certified building. It faces busy Old York Road and is surrounded by many other houses of worship that represent a wide variety of religions. The main building was erected in 1861 and expanded forty years later by noted architect Horace Trumbauer, most famous for his design of Peter Widener‘s nearby residence, Lynnewood Hall (which is sadly neglected and deteriorating) and his collaboration on the design of the renowned Philadelphia Museum of Art. Behind the 19th century Gothic-style stone structure is a two-level cemetery that was laid out in 1879 and is the eternal resting place of some pretty interesting figures from history – some of local interest and some of national significance. After driving by the cemetery countless times, I decided to take a stroll through and see who I could find.

Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church is a typical neighborhood church with an active congregation that still holds services in the historically-certified building. It faces busy Old York Road and is surrounded by many other houses of worship that represent a wide variety of religions. The main building was erected in 1861 and expanded forty years later by noted architect Horace Trumbauer, most famous for his design of Peter Widener‘s nearby residence, Lynnewood Hall (which is sadly neglected and deteriorating) and his collaboration on the design of the renowned Philadelphia Museum of Art. Behind the 19th century Gothic-style stone structure is a two-level cemetery that was laid out in 1879 and is the eternal resting place of some pretty interesting figures from history – some of local interest and some of national significance. After driving by the cemetery countless times, I decided to take a stroll through and see who I could find.

Just through the unlocked, wrought-iron gate is the lower-level of the churchyard. The grounds are well-maintained and the graves, some dating back to the late 1800s, are in pretty good shape. Just ahead, under a large shade tree, is the grave of Ario Pardee, Jr.

Pardee was the son of Ariovistus Pardee. After coal was discovered in northern Pennsylvania’s Luzerne County area by Tench Coxe, the senior Pardee, a surveyor, bought up the land surrounding Coxe’s stake, thus founding the town of Hazleton, Pennsylvania, a thriving industrial coal-mining town. Young Ario Pardee Jr., after completing civil engineering courses, joined the 28th Pennsylvania Infantry in 1861. He advanced to the rank of major and was critical of Colonel John Geary, his commanding officer, especially his strategy in the Battle of Thoroughfare Gap. Pardee later fought in the Battle of Culp’s Hill in Gettysburg (where a field was named in his honor). By the end of the Civil War, Ario Pardee Jr. achieved the rank of brigadier general. After his military discharge, a battle-weary Pardee took a passive role in his family’s coal business. After the death of his wife, Pardee became irritable and withdrawn, preferring to keep to himself. He passed away in 1901. His adopted home, Elkins Park, honored his memory by naming a narrow, winding road after him.

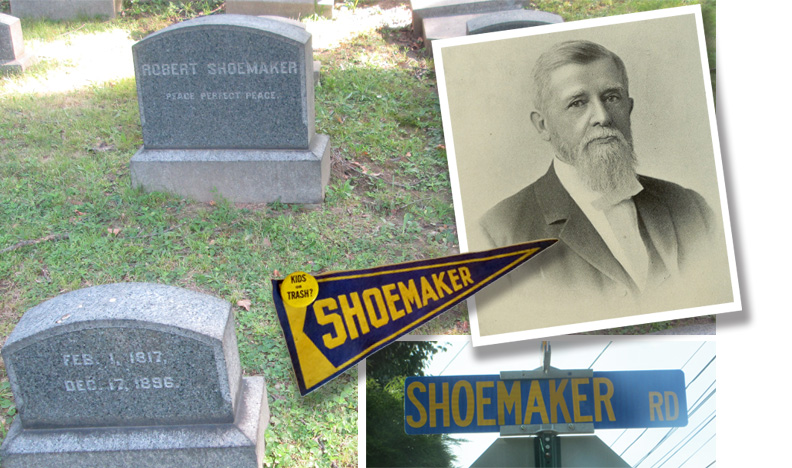

Behind the graves of Ario Pardee and his wife is the Shoemaker family plot. Here is the grave of Robert Shoemaker. Sure, his name means practically nothing to those outside of the northern Philadelphia suburbs, but he holds a special place for us locals.

Robert Shoemaker was a prominent druggist in 19th century Philadelphia. He was a trustee of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and served as president of the Philadelphia Drug Exchange. Shoemaker served on the board of directors of several insurance companies as well. For fifteen years, Shoemaker was the director of the Cheltenham School district, based in Elkins Park.

My wife attended the elementary school named in Shoemaker’s honor (and the road named for him crossed her street near her home). During her time there, a proposal was made to build a recycling facility that would impede upon the school’s ball field and playground. A massive campaign was mounted by the students and teachers against the local government. The “powers-that-be” essentially ignored the protests. Roads were rerouted. Families were relocated and their houses were then torn down. The recycling facility was built and Shoemaker Elementary School, a beautifully-striking stone building that stood on Church Road, was closed, eventually demolished and replaced by a library in a modern-designed building.

My wife attended the elementary school named in Shoemaker’s honor (and the road named for him crossed her street near her home). During her time there, a proposal was made to build a recycling facility that would impede upon the school’s ball field and playground. A massive campaign was mounted by the students and teachers against the local government. The “powers-that-be” essentially ignored the protests. Roads were rerouted. Families were relocated and their houses were then torn down. The recycling facility was built and Shoemaker Elementary School, a beautifully-striking stone building that stood on Church Road, was closed, eventually demolished and replaced by a library in a modern-designed building.

I climbed a small set of stone steps to the upper level of the cemetery where, among an arrangement of nondescript headstones, I spotted the monument atop Nancy Gilbert’s grave.

Nancy, who passed away at the young age of 27, holds the distinction of having the only grave in Saint Paul’s Churchyard that sports a piece of statuary that isn’t a cross.

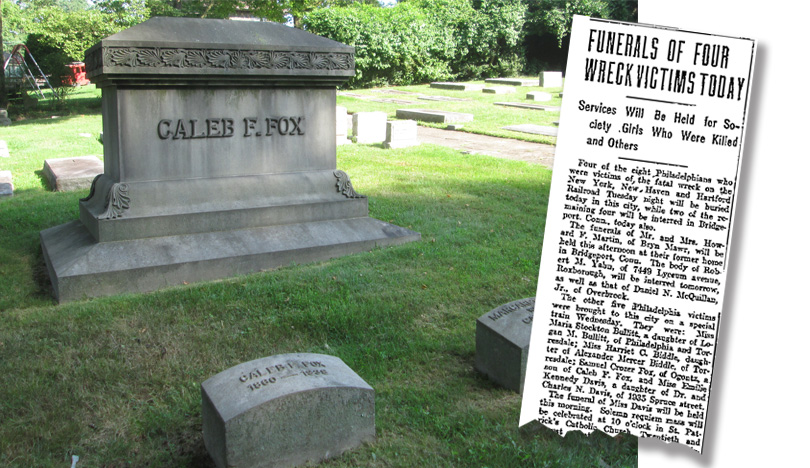

Just ahead of Nancy’s plot, a large, imposing and ornate marker designates the family plot of Caleb F. Fox.

Fox and his brood were members of Philadelphia’s so-called “high society.” In 1913, Caleb’s son, 24 year-old Samuel, was returning home from a camping trip in New England, accompanied by some of his friends from Philadelphia’s “upper crust.” Their train was rear-ended by another passenger train and all were killed.

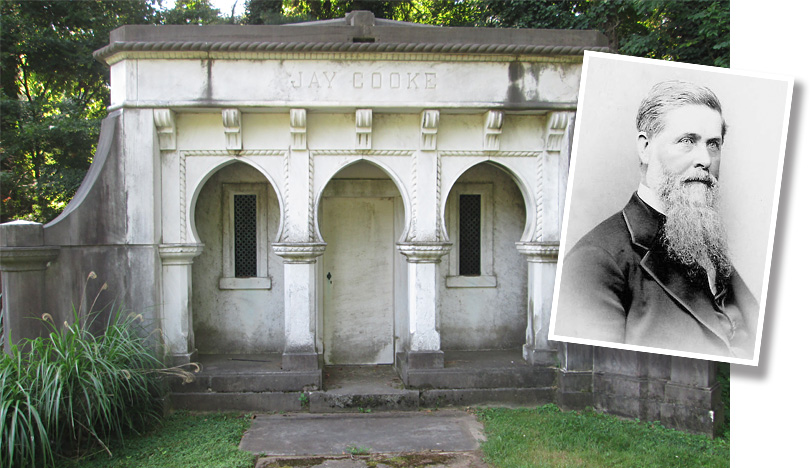

At the end of a cement walkway, surrounded by various trees and foliage, is the cemetery’s single mausoleum. It is the final resting place of Saint Paul’s Churchyard’s most prestigious resident, Jay Cooke. Curiously forgotten by most history books, if it wasn’t for Cooke’s financial strategy and marketing prowess, the Civil War could have had a decidedly different outcome.

A native of Sandusky, Ohio, Cooke came to Philadelphia in 1838. He opened a private bank and financing organization called, fittingly, Jay Cooke & Company. Just after the Civil War began, the state of Pennsylvania borrowed three million dollars from Cooke to fund its war efforts. Additionally, while working with Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, Cooke sold five hundred million dollars in war bonds. Originally, the US Treasury attempted — and failed — to sell these bonds themselves. But Cooke, through an aggressive campaign of newspaper editorials, articles, handbills, circulars, and signs, appealed to Americans’ desire to turn a profit, while simultaneously aiding the war effort. Cooke, through a network of sub-contractors, sold eleven million dollars more in bonds on top of his original commitment.

After the war, Cooke’s company financed the construction of the Northern Pacific Railway. His firm, however, overestimated the operation and the Depression of 1873 brought the project to a halt. Cooke himself was forced into bankruptcy. However, a wise investment in a Utah silver mine in 1880. made Jay Cooke a wealthy man once again.

Just across from the Cooke mausoleum is the grave of Cooke’s son-in-law, Charles Barney.

Barney, the son of a grain merchant and a veteran of the Civil War, moved to Philadelphia and married Laura Cooke, daughter of respected Philadelphia financier Jay Cooke. When Cooke’s business collapsed, it was Barney who brought it back to prominence. He offered his father-in-law a minority partner position in the new firm. In 1938, Charles Barney merged his firm with that of Edward B. Smith to form Smith Barney. The merged institution was a major player in international finance and, after a series of subsequent mergers, became part of Morgan Stanley. When he passed away at 101 years old in 1945, he was one of the oldest living veterans of the Civil War.

Just over a fence on the back part of the property, I saw this unusual sight…

I was tempted to take a ride on that colorful train, but I had a few more places to go this morning.

If you have ever pondered the origins of street names in your neighborhood, or wondered about the identity of those for whom local buildings are named, sometimes the answers are as close as your nearest cemetery. Don’t be scared to explore.

Some of them even have playgrounds.

* We just were overtaken by Phoenix, Arizona. They don’t have soft pretzels or the Liberty Bell.

* * * * *