While on a recent trip to the Pez Factory Visitors Center, I found myself in a cemetery. This is the second time I followed a Pez-centric event with a trip to a cemetery. Funny how that works. What can I say… I like Pez and I like cemeteries. Actually, I made it to two cemeteries in southern Connecticut, both equidistant from the Pez Factory and both filled with history.

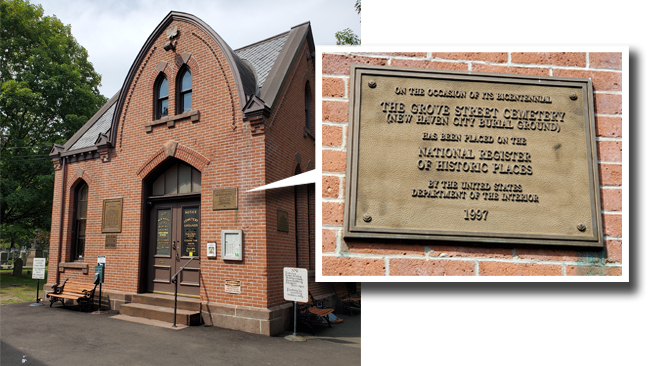

Touring the Pez Visitors Center, while very interesting, took way shorter than expected, so my wife and I moved our Sunday plans to Saturday afternoon. We headed back up I-95 towards our New Haven hotel. A short distance away is Grove Street Cemetery, surrounded on all sides by the majestic and decidedly college-looking buildings of Yale University. We found plenty of parking just outside the imposing entrance gate. After stopping to take a few pictures — backing up as far as possible to get the entire thing in one shot — we headed inside.

The entrance gate was designed in the Egyptian Revival style by New Haven architects Henry Austin and Hezekiah Augur, both of whom are interred here. Above the entrance is inscribed “The Dead Will Be Raised,” a somewhat eerie sentiment for a cemetery. It is actually a quote from 1 Corinthians 15.52 in the New Testament. Arthur Twining Hadley, who served as Yale’s president for 22 years, quipped in regards to the inscription: “They certainly will be, if Yale needs the property.” He, too, is buried here. Hadley died while visiting Japan. When his body was shipped back to the United States for burial, he had been dressed in full, traditional samurai garb, complete with gold robe, breastplate and sword… and that exactly how he was buried.

Grove Street is filled with historical figures, familiar names and the remains of no less than 14 former Yale University presidents. It is simply laid out with clearly marked street signs designating the rows of graves. Grove Street was established with the idea of family plots for a more organized and uniform layout. It certainly is the most easily navigable cemetery I have ever visited. It is also the first private, nonprofit cemetery in the world.

There are a lot of plots that look like this. A group of similarly-carved headstones surrounding a larger “family” marker. Keeping it in the family is what Grove Street Cemetery is all about.

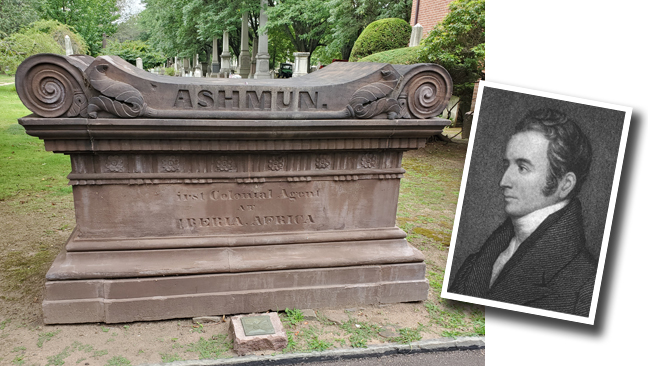

The history begins immediately upon entry. Right next to the gate house is the grave of Jehudi Ashmun.

A religious leader and social reformer, Ashmun became involved in the American Colonization Society. He founded the African colony of Liberia as place to settle freed people of color from the United States. Unlike its neighbor Sierra Leone, Ashmun, made sure that Liberia allowed for people of color to hold government office. Ashmun himself emigrated to Liberia in 1822 and essentially served as the country’s first governor. (Grove Street Cemetery is bordered by Ashmun Street along its rear wall.)

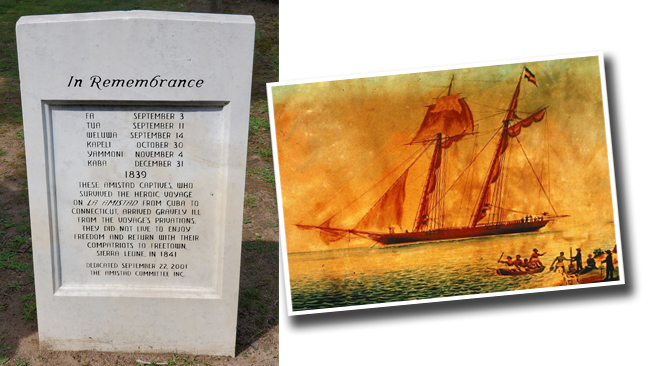

Alongside Ashmun’s grave is a memorial to six men who died before reaching the United States.

They were potential slaves aboard the notorious ship La Amistad en route from Cuba to New England. A violent takeover by captives aboard brought the ship into port with most of its crew dead. The events are depicted in the 1997 Steven Spielberg film Amistad.

Just past Ashmun’s crypt is the large obelisk that marks the grave of Jedidiah Morse.

Morse earned the nickname “Father of American Geography,” based on his interest and dedication to teaching and providing geography textbooks to his students, something that did not previously exist. Jedidiah Morse was the father of painter and telegraph pioneer Samuel F.B. Morse.

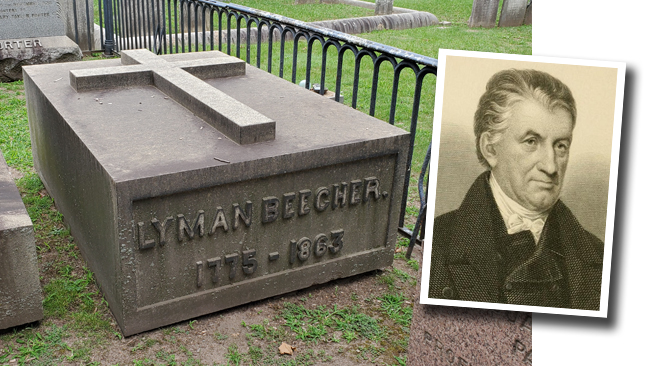

Not too far from Morse is the fenced-in family plot where Lyman Beecher is interred.

Beecher was a lot of things. He was a Presbyterian minister. He was a fervent abolitionist. He was an advocate for women’s education and was an outspoken critic of the Unitarian Church. He was the father of 13 children including Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher.

One of the most famous names among those buried at Grove Street Cemetery is Eli Whitney.

Any elementary school student can tell you that Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin. Any graduate of elementary school can tell you that Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin. Whenever a Jeopardy! question mentions “the cotton gin,” you know the answer is going to be “Eli Whitney” and suddenly you feel smart. Unfortunately, what exactly the cotton gin does is sort of a mystery. Sure, it’s probably a beneficial piece of farming… or harvesting… or manufacturing equipment, but I can’t — for the life of me — tell you why. (That lovely piece of machinery below Whitney’s photo is the notorious cotton gin.)

Whitney’s next-plot neighbor at Grove Street is Noah Webster.

Webster, of course, compiled and published the Webster’s dictionary, an indispensable reference book rendered obsolete by the internet. Fortunately, the online version of Webster’s tome has proven just as essential as its printed version.

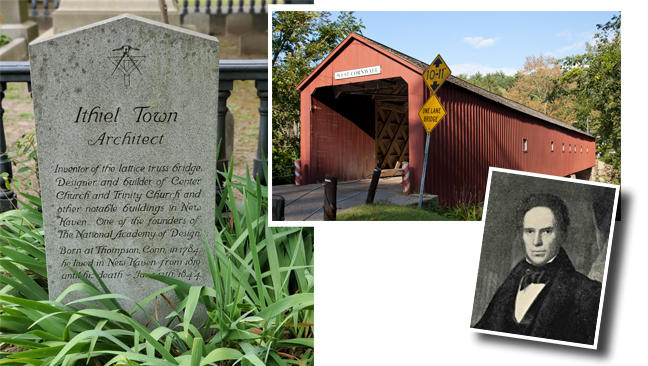

Across Cedar Street and down a little bit lies architect and engineer Ithiel Town.

Town was a prominent architect in Connecticut and the surrounding area. He invented and patented the lattice truss bridge, the design of which is still in wide usage today.

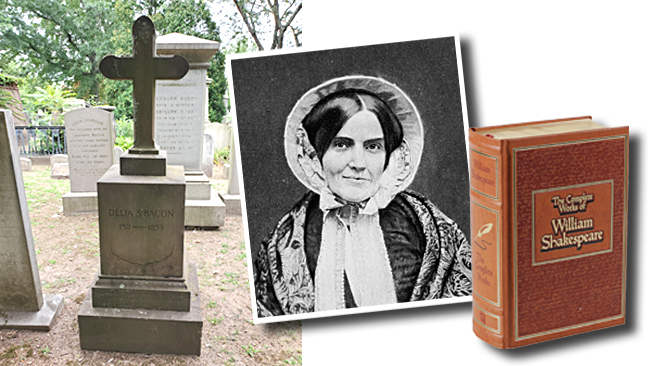

Buried in a family plot near the Town grave is Delia Bacon.

A one-time educator and lecturer, she withdrew from public life in 1845 to concentrate on her theory that all of the plays attributed to William Shakespeare were actually written by Francis Bacon. Delia was befriended by famous writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne and Ralph Waldo Emerson, although it is unclear whether or not they subscribed to her beliefs. Scottish philosopher and satirist Thomas Carlyle, although intrigued by her idea, audibly scoffed when it was first presented to him.

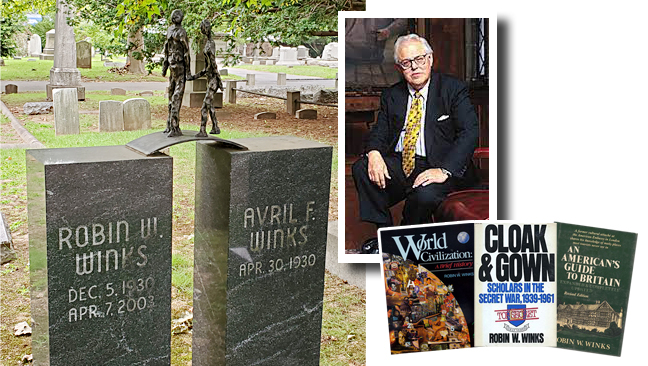

The modern art sculpture on the double grave of Robin Winks caught my attention as I walked.

Winks was a historian and professor at Yale. He was a prolific author, writing or co-writing dozens of books on a wide variety of subjects. I found the simple figures spanning his grave marker and the future resting place of his wife particularly touching.

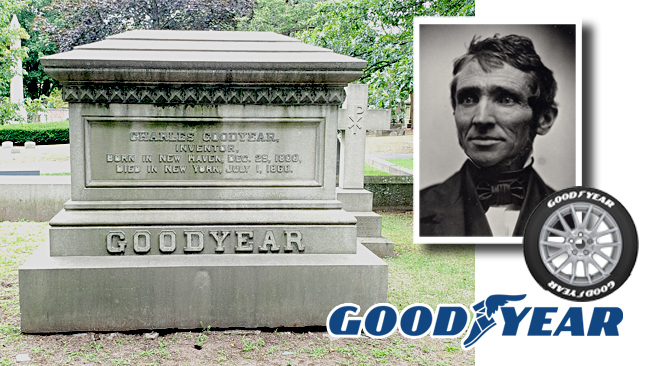

At the end of Cedar Street is the massive tomb of Charles Goodyear.

Goodyear invented the chemical process to create and manufacture pliable, waterproof, moldable rubber — despite having no formal training in chemistry. Many people used Goodyear’s discovery for applications of their own, including waterproof footwear and, of course, tires. One of his licensees was Benjamin Goodrich. The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, was founded almost 40 years after Charles Goodyear’s death. It was named in his honor.

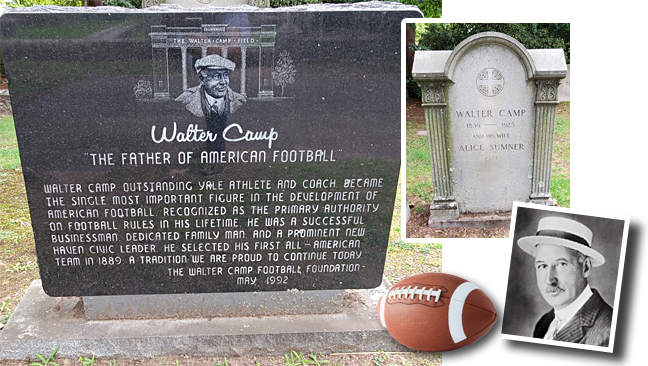

Across from Goodyear is Walter Camp.

Unlike Abner Doubleday, who couldn’t tell a double-play from a double steal, Walter Camp was — indeed — the “Father of American Football.” As a player and eventual coach, Camp was on collegiate rules committee. He developed such standard football practices and procedures as the snap from center, the system of downs, and the points system as well as the introduction of what became a standard offensive arrangement. He also created the “safety” and the two-point award that goes with it, “line of scrimmage” and he cut number of on-field players from 15 to 11. Abner Doubleday, while an “okay” general during the Civil War, probably never even saw a baseball game.

We noticed dozens and dozens of thin, fragile and very weathered headstones leaning neatly against the wall that delineates the perimeter of Grove Street Cemetery.

A little research revealed that a number of graves in Grove Street were relocated from New Haven Green, which is now a public park. In 1794 and 1795, a yellow fever plague swept the town and New Haven Green was running out of burial space. A new cemetery — Grove Street — was established. But, in what later mirrored the jarring plotline from the film Poltergeist, only the headstones were moved. The bodies were left behind and still turn up from time to time during excavation projects or, more recently, when an ancient tree was uprooted during a major storm.

Tucked into a little corner of a flat green lawn is the final resting space of Bart Giamatti.

Giamatti was the 19th president of Yale University until he was named President of Major League Baseball’s National League. After served in that position for just under three years, he was named Commissioner of Major League Baseball on April 1, 1989. During his term as Commissioner, Giamatti upheld Pete Rose’s agreement to voluntarily remain permanently ineligible to play baseball. Just eight days after his banishment of Rose, Giamatti died from a heart attack. Bart Giamatti was the father of actor Paul Giamatti.

Just a few plots over from Bart Giamatti, I found this little surprise…

Near the center of the cemetery is a cenotaph placed in memory of band leader Glenn Miller.

Miller was one of the swing era’s most popular big band leaders. As a Major in the US Army Air Force, his plane was reported missing over the English Channel in December 1944. His body was never recovered.

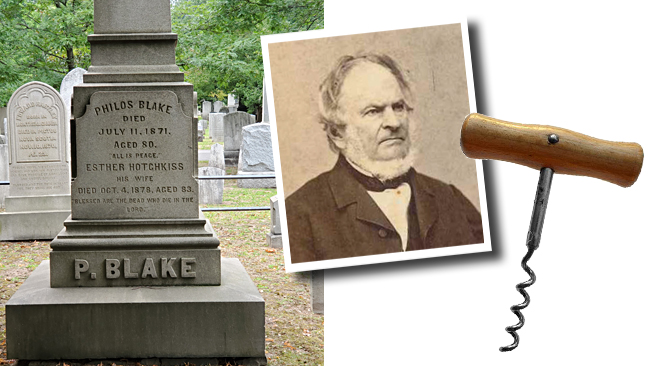

Eli Whitney has a couple of “inventive” nephews buried at Grove Street.

Eli Whitney Blake invented the mortise lock as well as the stone-crushing machine, which, I can only assume, offered ease in the difficult task of crushing stones.

Eli’s brother Philos Blake invented something that — heaven knows! — none of us could live without. You can thank Philos Blake for the corkscrew.

Along the far wall is this monument to James T. Hemingway.

Hemingway was a one-time chief of the New Haven Fire Department. He died while fighting a fire in 1852.

Right next to Hemingway is this cryptic marker…

No name. No epitaph. Just a date. All we know is it is somebody’s mother.

Along Myrtle Street, the single street that bisects all the other streets at the cemetery’s center, is a pair of nearly identical Grecian-style sphinx that do not appear to belong to any one grave or plot.

There is a marble bench that is engraved with the name “Chiarelli,” but it is set back from the massive figures. According to Find-A-Grave.com, the winged creatures are decoration for the Chiarelli plot, but it is really not clear.

Closer to the front entrance is the striking grave of Robert Reed Jr.

Reed was a respected abstract artist. In 1987, he was appointed to Yale School of Art’s tenured permanent faculty, making him, at the time of his death, the school’s first and only African-American to be so appointed in Yale’s 145 year history.

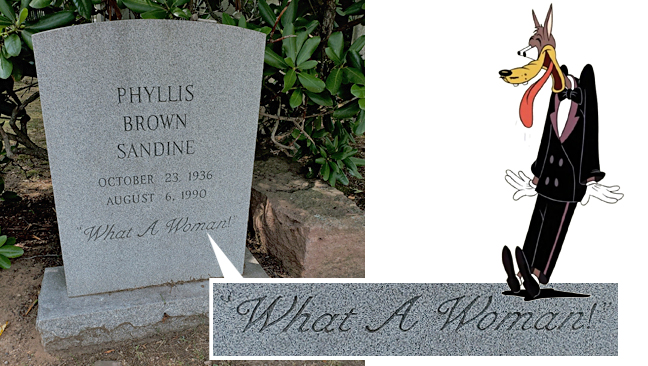

Nearby is the grave of Phyllis Sandine.

Sandine’s headstone is one of the most photographed in all of Grove Street.

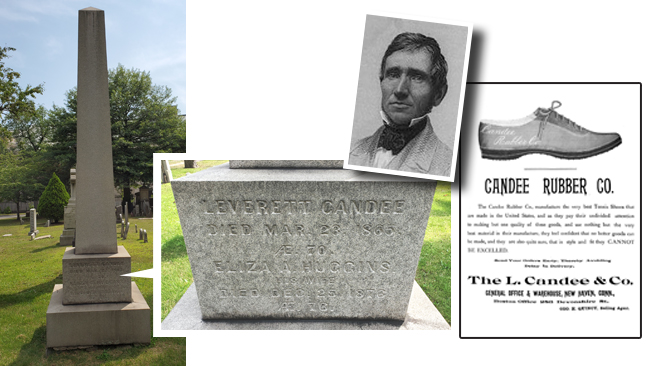

This worn obelisk marks the grave of Leverett Candee.

Candee was the first person to find commercial use for Charles Goodyear’s revolutionary vulcanized rubber. He manufactured and sold waterproof shoes to much success, becoming the first person in the world to manufacture rubber footwear.

Here is the grave of Martha Townsend.

She was the very first interment at Grove Street Cemetery. Curiously, she is buried just outside the confines of the fenced-in Townsend Family plot, just next to her grave.

Across from Martha Townsend is Roger Sherman.

Sherman is the only person to have signed the four major documents of American sovereignty, the Continental Association, the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution. I’m sure he signed other things, but it’s those particular four that got him in the history books.

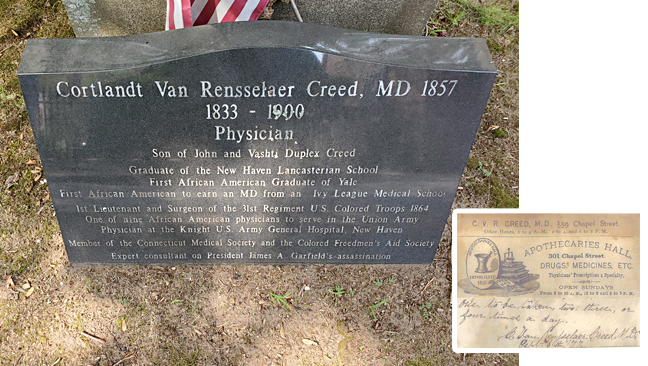

We found ourselves back at the front entrance gate, in front of the grave of Cortlandt Van Rensselaer Creed.

In 1857, Creed became the first African-American graduate of Yale Medical School and was the first person of African descent to receive any sort of degree from Yale. There are many photos online of Dr. Edward A. Bouche, the first African-American to receive a PhD, that are misidentified as Cortland V.R. Creed. Apparently no photos of him exist… not even in the Yale archives. Above is a prescription form from Dr. Creed’s office.

We checked to make sure we had not broken any of the cemetery’s rules and headed back to our hotel.

On our way back to Philadelphia, we made a quick stop in Bridgeport, Connecticut to visit Mountain Grove Cemetery. It was drizzling a bit, but that didn’t stop us from a morning of grave hunting. Mountain Grove is huge, home to over 40,000 graves and a bunch of twisting, winding roadways that make this cemetery fairly difficult to navigate without a concise map. The land was purchased in 1849 by show business impresario P.T. Barnum for specific use as a cemetery. It was laid out by sculptor Horatio Stone, best known for his three statue commissions on display at the U.S. Capital — John Hancock, Alexander Hamilton, and Edward Dickinson Baker. Mountain Grove was is first and only attempt at landscape design.

Near the Dewey Street entrance, I tramped through the wet grass to the grave of Neal Ball.

Ball was a Major League Baseball player, who ended his rookie season by committing the most errors by a shortstop and the most errors by any type of fielder. However, in 1909, his first year with the Cleveland Naps, Ball executed the first unassisted triple play in Major League history. The play happened so fast that Ball’s team mates (including starting pitcher Cy Young) were visibly confused as to what just transpired. In his next plate appearance, Ball hit an inside-the-park home run. He ended his career as player/manager for his hometown Bridgeport Hustlers, a minor league team.

A few sections over is a black marble slab inscribed “Marion T. Slaughter Sr.”

This is the grave of singer Vernon Dahlert. With hopes of becoming an opera singer, Slaughter, using the stage name “Vernon Dahlert,” landed parts in several operas. In 1916, he auditioned for Thomas Edison and began recording for Edison records, as well as other labels. Between 1916 and 1923, he made over 400 recordings. In 1924, his recording of “Wreck of the Old 97” became the first country music record to sell one million copies. During the ’20s and ’30s, it is believed that Dahlert sang on well over 5000 recordings, sometimes employing over 100 different pseudonyms.

Nearby is a plot of land designated for the burials of Connecticut casualties and veterans of the Civil War.

The section is marked my an imposing granite stele monument with a patinaed bronze plaque. The granite is inscribed “Pro Patria” which means “For Country.” Mrs. Pincus was especially moved by this monument and the graves for which it stands.

On our way to the other side of the cemetery, we passed this sad remembrance for young Allie Hopkins.

The brown marble base displays a full bronze figure of Allie who was just 10 years old when he died. This is obviously the work of family who dearly missed this young man.

Just ahead is the grave of Fanny Crosby.

At six weeks old, Crosby caught cold and developed an inflammation of the eyes. The primative treatment prescribed caused her to lose her eyesight. Raised by her mother and grandmother with strict Christian principles, young Fanny Crosby memorized long Bible passages and began writing hymns. It is estimated that, over the course of her life, she wrote over 8,000 hymns and gospel songs. Some publishers were adverse to publishing songbooks where all of the hymns were by a single author. To make everyone happy, Fanny began writing under a variety of pen names.

At the far end of Mountain Grove is the grave of P.T. Barnum.

World-renowned as a showman, exploiter and collector of interesting and unusual oddities, Barnum was always seeking out the next big thing. From the “FeJee Mermaid” to “Joice Heth,” who he claimed was 161 years old and served as George Washington’s nursemaid, Barnum could sell his adoring public anything. In 1842, Barnum recruited four year-old Charles Stratton from his parents and promoted the young man as 11-year old “General Tom Thumb.” Stratton was just 25 inches tall. Barnum dressed Charles in military regalia, as well as costumes depicting Cupid and Napoleon. He had the boy smoking cigars and drinking at age five, all for the public’s amusement. Barnum passed away in 1891, gaining quite a reputation — in his later years — as a philanthropist, owing to a number of generous donations and endowments to various cultural organizations. He even served as Mayor of Bridgeport for a year. Barnum is famous for saying “There’s a sucker born every minute,” although there is no record or documentation of him ever saying that.

Buried right across from Barnum is “General Tom Thumb,” Charles Stratton.

He was one of P.T. Barnum’s biggest attractions (no pun intended) and Barnum was devastated when he died of a stroke at the age of 45. His funeral was attended by over 20,000 mourners. P.T. Barnum purchased a life-size statue of Stratton and had it placed at the top of his tall grave marker. In 1959, vandals smashed the statue, but was restored by the Barnum Festival Society and Mountain Grove Cemetery Association with funds raised by public contributions.

The rain was starting to pick up, so we retraced our path back to the entrance and started for home.

* * * * * * *