I have visited the final resting places of the famous and almost famous in California, Ohio and New York. On a recent cold December morning, I took a short trip to see the graves of some notable people right in my own backyard. (No, not those people. I’ll never reveal the location of those bodies…. wait…. what was I talking about?)

My first stop was Laurel Hill Cemetery, seventy-eight acres of narrow winding roads cluttered with concrete angels, granite obelisks and weather-worn marble headstones. Laurel Hill is one of only a handful of cemeteries to be honored with the designation of National Historic Landmark, a distinction it received in 1998. The majority of noteworthy permanent residents are Revolutionary and Civil War heroes and dignitaries whose fame only reaches to the furthest boundaries of Philadelphia and the greater Delaware Valley. However, a number of the graves I visited hold the remains of those who, while merely footnotes in the long history of this country, claim an interesting contribution to that history.

Laurel Hill is perched on a slender stretch of land along the banks of the Schuylkill River. Regular commuters on Philadelphia’s notorious Route 76 and serpentine Kelly Drive can spot its larger monuments and imposing mausoleums poking through the trees and looming over the stone barrier walls as they navigate through traffic. I drove up Ridge Avenue and, armed with what I hoped was an accurate map of the grounds (it wasn’t), I passed through the entrance and forced my car up the first steep road towards Section X of Laurel Hill. Here, I immediately found the grave of Sarah Hale.

Sarah relentlessly campaigned for Thanksgiving, a celebration popular in her native New Hampshire, to become a national holiday. She wrote letters to five U.S. Presidents until Abraham Lincoln finally supported legislation for the Thanksgiving holiday in 1863. A prolific writer of novels and poetry, Sarah wrote “Mary Had a Little Lamb” in 1830 and was the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book for 40 years, a popular publication that numbered such famed authors as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Washington Irving and Edgar Allen Poe among its contributors.

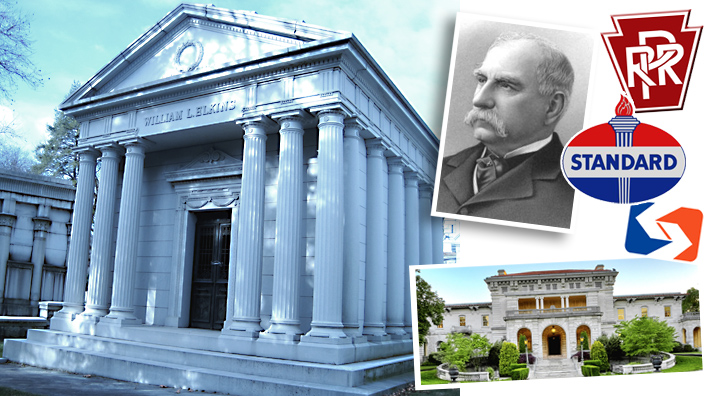

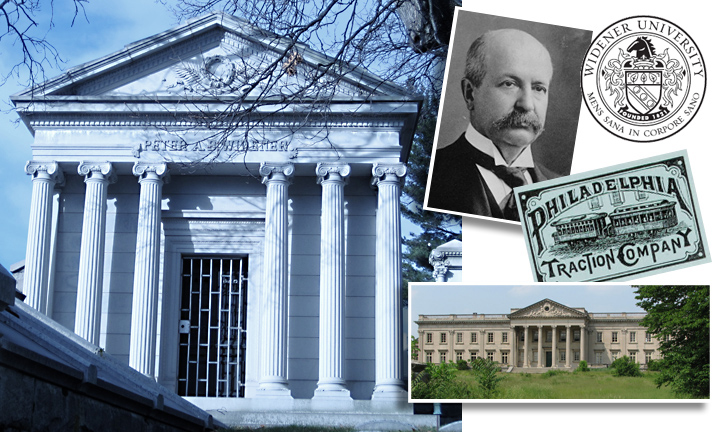

Sarah’s grave was, unfortunately, the first and last one I had ease in locating. Pinpointing the remainder of my list, based on my lack of proper map-reading skills, proved difficult. Ever-determined, I made my way over to the section of Laurel Hill affectionately known as “Millionaire’s Row”. This area, populated by mausoleums one bigger than the next, boasts business partners, suburban neighbors and neighbors in death, William Elkins and Peter Widener.

William Elkins was a partner in Standard Oil and The Pennsylvania Railroad. He and Peter Widener partnered in the public transportation company that was the forerunner to SEPTA, Philadelphia’s current mass transit company. Widener also endowed the educational institution that became Widener University. Elkins’ daughter even married Widener’s son. Elkins and Widener also each commissioned architect Horace Trumbauer to build massive summer homes in nearby Montgomery County (in a municipality now called “Elkins Park”, where I’ve made my home for the past 25 years). Elkins Estate is a 45-room opulent mansion built in the Italian Renaissance style. Widener’s home, Lynnewood Hall, was a 110-room sprawling complex built in the Georgian style. While both estates still stand today (several blocks from my house, no less!), Elkins Estate is in bankruptcy and Widener’s property is in an awful state of disrepair.

Also in the same section is the family crypt of J. Bertram Lippincott of the prominent publishing family, originating in Philadelphia.

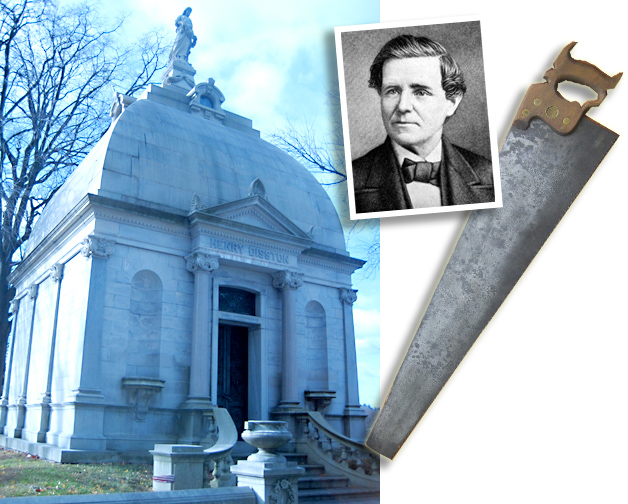

Henry Disston founded Disston Saw Mill, the largest hand saw manufacturer in the world. As an extension of his business, Disston developed the current Tacony neighborhood in Northeast Philadelphia, the only company town in the United States established within an existing city.

A narrow, steep and winding gravel road led me to the grave of Hall of Fame broadcaster Harry Kalas.

For thirty-nine seasons, Harry’s voice was the voice of the Philadelphia Phillies. Harry was a hugely popular figure among Phillies fans, with his inimitable home-run calls of “Outtta HEEERE!” His untimely death in 2009 dealt a major blow to local baseball fans who now have to tolerate Harry’s insufferable successor Tom McCarthy. Harry’s grave is marked with a large (if a bit phallic) granite microphone into which is carved a replica of the commemorative “HK” patch the Phillies wore on their uniforms after his death.

Laurel Hill features unusual, if not creepy, statuary throughout the grounds. One grave, the Warner Family plot, features a sculpted figure lifting the lid of an elevated stone casket to free a sculpted stone spirit.

As I approached to take this photo, I was startled by this adjacent life-size statue in the same plot.

The sculptures on William Warner’s grave were created by famed artist Alexander Milne Calder, who also created over 250 marble and bronze figures that adorn Philadelphia’s City Hall, including the 37-foot bronze statue of William Penn, the tallest statue atop any building in the world.

My next destination for others’ final destinations was West Laurel Hill Cemetery, “sister” cemetery to the Philadelphia property, located in Bala Cynwyd (pronounced “Bala Kin-wood” for you non-Philadelphians). On the day of my visit, West Laurel Hill was the site of major construction and renovation. Its narrow arteries were clogged with forklifts and flatbed trucks. Many of the sites I had marked on my hand-drawn map were blocked by cement burial liners and temporary construction fences. Because of this, I was denied access to the graves of West Laurel Hill’s two most famous residents — singer Teddy Pendergrass and jazz saxophonist Grover Washington, Jr. Despite that slight inconvenience, I was able to locate several other distinguished names.

The first marker I spotted, just inside the entrance gate, was that of local radio legend Hy Lit. (It says so right on his headstone!)

“Hyski”, as he was known to his fans, was the second most beloved and annoying DJ in Philadelphia radio history (after the still-living Jerry Blavat).

Speaking of local legends, I stumbled upon the crypt of Sam Barson, founder of “Barson’s Deli”, a chain of eleven delicatessens in the Philadelphia area. His grave site even proclaims him as “The Deli King” and you don’t argue with a dead guy’s claims.

(That’s a “Hymie’s Deli” pen sitting on the ledge. Hymie’s Deli was opened by the Barson family.)

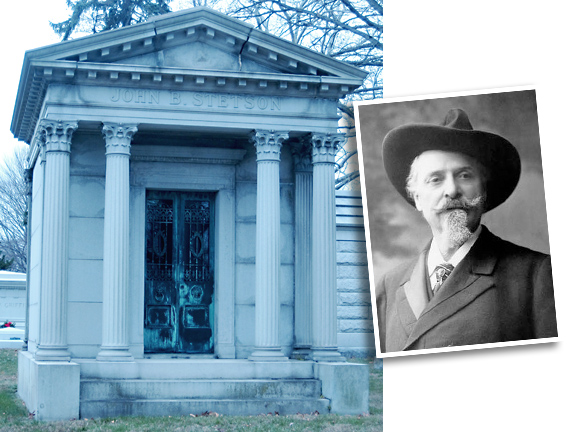

Here is the mausoleum of a more globally-renowned name, John Stetson.

Stetson’s manufacturing company made hats suited to the needs of the Westerners. Before Stetson’s invention in 1860, there was no such thing as a “cowboy hat”. Stetson’s hat became the symbol of high-quality Western head wear and was sported by icons from Buffalo Bill Cody to The Lone Ranger.

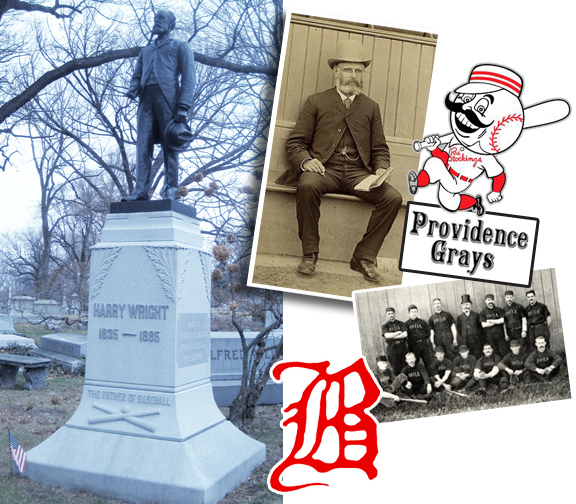

Opposite West Laurel Hill’s administration building stands the memorial for Harry Wright, “The Father of Baseball.” (Well, it says so right there on the statue’s base — damning any assertion made by Abner Doubleday. Remember what I said about arguing with the dead?)

Harry was the founder of the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first professional baseball team. He also managed the Boston Red Caps (who later became the Boston, and then Milwaukee and, ultimately, Atlanta Braves), The Providence Grays and The Philadelphia Quakers (later to become the Phillies).

Another name in Philadelphia baseball history is Benjamin Shibe.

Shibe and his partner, Connie Mack, were the co-owners of the Philadelphia Athletics. He also invented the machinery for the manufacture of standard baseballs. Shibe Park, the A’s stadium, was named in his honor… until 1953, when its name was changed to Connie Mack Stadium.

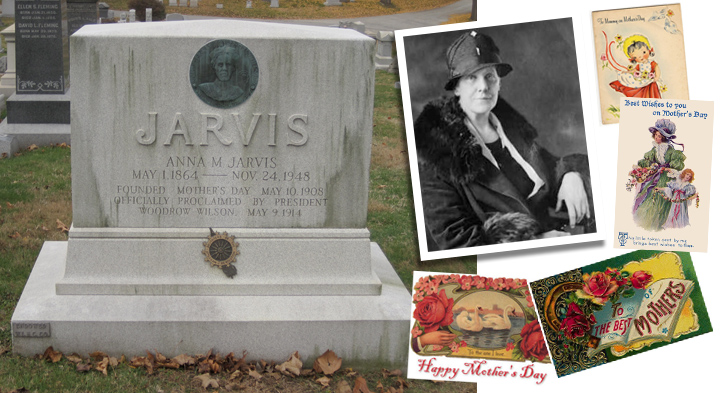

In the far reaches of the cemetery stands the grave of Anna Jarvis.

Two years after her mother’s death, Anna Jarvis held a memorial to her mother and thereafter embarked upon a campaign to make “Mother’s Day” a recognized holiday. She succeeded in making this nationally recognized in 1914. However, by the 1920s, Anna Jarvis had become angered by the commercialization of the holiday. She was once arrested for disturbing the peace during a protest of the holiday. She and her sister spent their family inheritance campaigning against what the holiday had become. Both died in poverty. According to her New York Times obituary, Jarvis became embittered because too many people sent their mothers a printed greeting card. As she said, “A printed card means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world. And candy! You take a box to Motherand then eat most of it yourself. A pretty sentiment.” Anna Jarvis never married and had no children.

My last stop, before I left, was for some warm refreshment.

Luckily, these places are popping up everywhere!

* * * * *

Informative and awesome (as always). You need to let me know the next time you line up one of these trips. I’d gladly come along and attempt to help navigate.