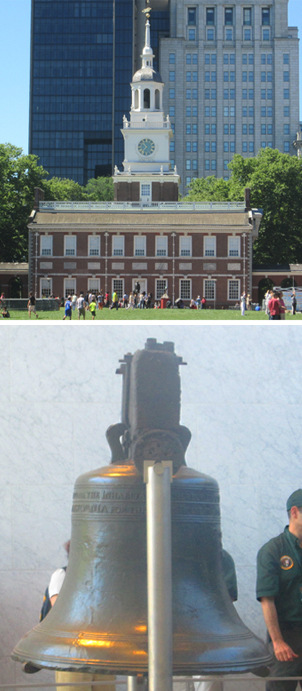

Just one day after our nation’s 238th birthday, I decided to mingle with the tourists and visit the city in which I grew up. I headed down Market Street to the section of Philadelphia colloquially known as “Olde City.” (Note the spelling of “olde,” in an attempt to sound… well…. old.) The sidewalks were jammed as crowds clamored to Instagram a photo of famed Independence Hall and Facebook a selfie with the Liberty Bell for the benefit of those who couldn’t make the trip.

Just one day after our nation’s 238th birthday, I decided to mingle with the tourists and visit the city in which I grew up. I headed down Market Street to the section of Philadelphia colloquially known as “Olde City.” (Note the spelling of “olde,” in an attempt to sound… well…. old.) The sidewalks were jammed as crowds clamored to Instagram a photo of famed Independence Hall and Facebook a selfie with the Liberty Bell for the benefit of those who couldn’t make the trip.

My destination was Christ Church Burial Ground, a shady 2-acre plot of land surrounded by a high, red brick wall and plain iron grating. Established in 1719, the small cemetery belongs to Christ Church which is just a few blocks away. The cemetery is filled with thin and eroded grave markers that have become more fragile and whose inscriptions have become more illegible as the years go on. Some have been replaced, but the remaining originals show cracks. There are some that are just worn stubs of once-larger stones.

Cemeteries, such as Christ Church Burial Ground, are like three-dimensional history books. They are a way to experience pieces of our nation’s infancy aside from some boring lesson delivered in monotone from an uninterested teacher. So, if you’re like me and got a “C” in 11th grade American History, maybe this little refresher course is just what you need.  Just inside the wrought iron gates of Christ Church Burial Ground is a small souvenir stand stocked with mass-produced, historical-looking trinkets and aged-looking, rolled parchment facsimiles of historical documents. It is here that visitors pay a nominal admission fee (two bucks; five for a guided tour) to enter the cemetery (A first for me in all my years of cemetery visits, however I didn’t mind making the donation.) The two gentlemen manning the booth were friendly and helpful, which is always welcome at cemeteries and, believe it or not, isn’t always the case. On a small plot of grass down the first path, I found a newly installed cement bench. It is inscribed with the names of seven signers of the Declaration of Independence, five of which call this place their eternal home.

Just inside the wrought iron gates of Christ Church Burial Ground is a small souvenir stand stocked with mass-produced, historical-looking trinkets and aged-looking, rolled parchment facsimiles of historical documents. It is here that visitors pay a nominal admission fee (two bucks; five for a guided tour) to enter the cemetery (A first for me in all my years of cemetery visits, however I didn’t mind making the donation.) The two gentlemen manning the booth were friendly and helpful, which is always welcome at cemeteries and, believe it or not, isn’t always the case. On a small plot of grass down the first path, I found a newly installed cement bench. It is inscribed with the names of seven signers of the Declaration of Independence, five of which call this place their eternal home.

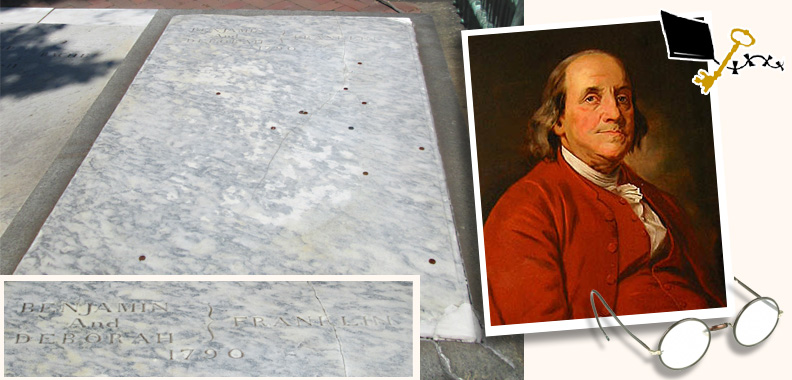

The most famous resident is Benjamin Franklin.

In addition to signing the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin was a printer, author, statesman, diplomat and scientist. He was a puppet, a pauper, a pirate, a poet, a pawn and a king. (Or maybe that was Frank Sinatra. I always get those two confused.) He started the first post office, library and fire department. He invented everything that Thomas Edison didn’t get around to inventing. And he was pretty popular with the ladies, if you know what I mean. In addition, his portrait appears on the one hundred dollar bill, earning it the street-cred nickname “benjamin.” so that makes ol’ Ben cooler than he already is.

Near Ben’s grave is the Clay Family vault, containing the remains of political cartoonist Edward Clay.

Clay, despite being a member of the Pennsylvania Bar, quit his law practice to become a full-time artist. His blatantly racist cartoons were featured in Life in Philadelphia, collection of scenes satirizing society life. It was loosely based on a similar European publication called Life in London. If his name seems unfamiliar, maybe Edward Clay was purposely left out of history books.

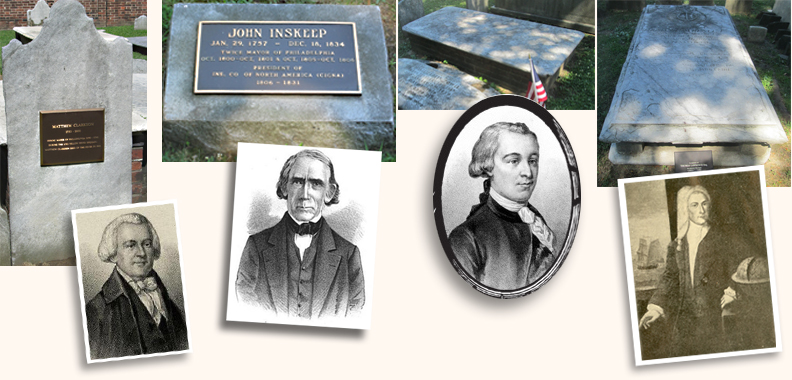

Many former Philadelphia mayors are in eternal repose at Christ Church Burial Ground, including:

Matthew Clarkson, who served four one-year terms from 1792–1796;

John Inskeep, who served two, non-consecutive terms and went on to serve as president of Insurance Company of North America (now part of CIGNA);

Samuel Powel, who served two terms, each on either side of the Revolutionary War (during which the office was vacant);

and Thomas Lawrence, who served five non-consecutive terms.

There are many war heroes represented here as well, including James Biddle.

Commodore Biddle negotiated the first treaty between the United States and China. His attempt at a similar agreement with Japan had adverse results. He was physically rebuffed by a samurai guard after he misunderstood instructions when boarding a Japanese junk.

The Cadwalader crypt holds many familial remains, including George Cadwalader.

Cadwalader was a brigadier general in the Mexican-American War and major general in the Civil War. He founded the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, an armed forces fraternal organization. He also sported an awesome haircut.

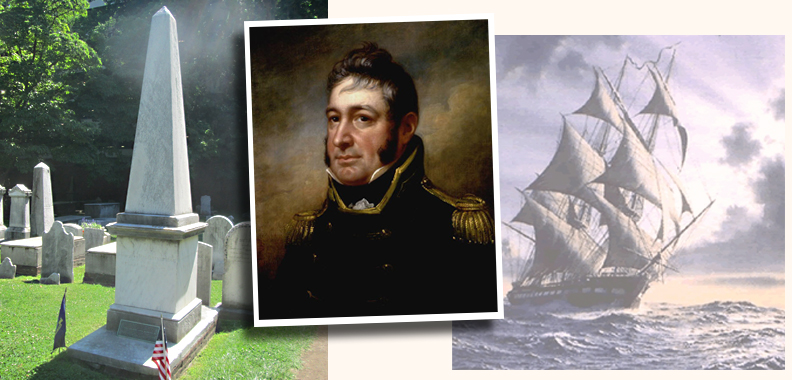

This obelisk marks the grave of Commodore William Bainbridge.

Bainbridge, who served under six presidents, is most famous as the commander of the USS Constitution, better known as “Old Ironsides.” Another guy with a pretty cool hair style.

Beneath this broken stone lies Edward Buncombe.

Colonel Buncombe served in the Continental Army. It is from his surname that the word “bunk” entered the lexicon. During a speech before the U.S. House of Representatives, a congressman evoked the colonel’s namesake North Carolina county during a lengthy and boring speech. From that, “bunkum” came to mean “nonsense.” Over time, it was shortened to “bunk.”

This plaque marks Edwin DeHaven’s grave.

Astoundingly, DeHaven’s became a midshipman at age 10. His claim to fame, however, was his participation in the Artic rescue mission to recover explorer Sir John Franklin. DeHaven and his crew spent 16 months at sea. John Franklin was discovered to be in “remains” form.

Another DeHaven was helpful to the Revolutionary War effort.

Peter DeHaven owned three gun factories and a tannery. He was able to supply the Continental Army with guns and shoes while they were camped at Valley Forge… sort of like a Colonial-era Zappos.com.

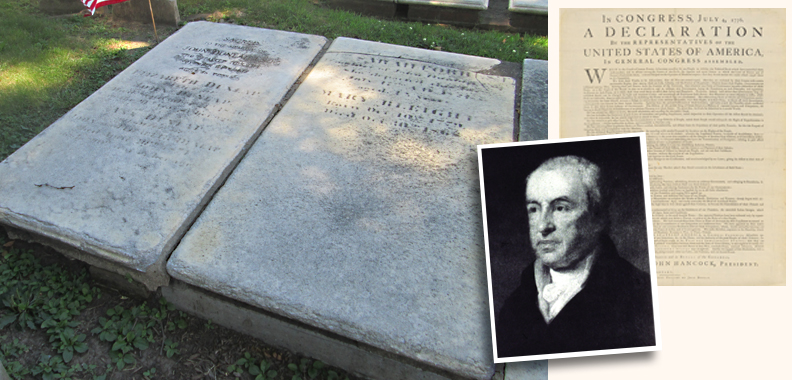

Of course, the Revolutionary War started when the thirteen colonies of the United States had had enough of the poor treatment from England. The Declaration of Independence was drafted and signed by fifty-six colonial representatives, including these guys:

Francis Hopkinson, a delegate from New Jersey and a customs officer in Delaware, was responsible for the design of the American flag. No, not working in conjunction with Betsy Ross. He did it all on his own. In May 1780, he sent a letter to Congress asking for payment for design of “the U.S. flag, the Great Seal of the United States.” He requested a quarter cask of wine. Congress asked for an itemized list of services provided. Then, Congress refused payment, saying that Hopkinson was already a paid public servant. Despite the controversy, there is no evidence in history that even mentions that Betsy Ross designed and sewed the country’s first flag. That claim is made purely by Betsy Ross’s descendants.

Speaking of Betsy Ross, her uncle George Ross is buried at Christ Church Burial Ground. He was a member of the Pennsylvania Bar and the last of the Pennsylvania delegates to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Another signer, Joseph Hewes, a delegate from North Carolina, was the first Secretary of the Navy, although the office had no title when he served.

In addition to signing the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Benjamin Rush was the founder of Dickinson College and is regarded as “The Father of American Psychiatry.” Although Rush served as Surgeon General of the Continental Army, he was a harsh critic of George Washington.

Annis Stockton is buried in the Rush Family plot. She was Benjamin Rush’s mother-in-law and the wife of Richard Stockton, making her related to two signers of the Declaration of Independence.

And thanks to John Dunlap…

…the delegates had something to sign. Dunlap, a printer, had the printing contract with the Continental Congress. On the evening of July 4, 1776 (after the barbecue and fireworks, I guess), he tirelessly set type and ran presses, printing approximately 200 copies of the Declaration of Independence for distribution. The copies were hastily printed and fraught with errors, both typographical and physical. Today, only 26 copies are known to exist, including one that was found behind a picture frame that was purchased at a flea market for $4.00. It later sold at auction for $8.14 million.

And where would they have been without Philip Syng?

Syng was a renowned silversmith who fashioned the Syng Inkstand (made to hold quill pens) that was used at the signing ceremony for the Declaration of Independence, and later, the Constitution. The stand is on display near the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia.

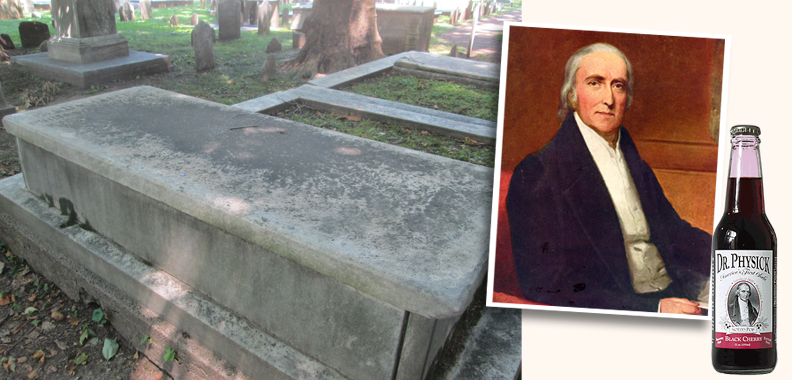

Across a small path from Philip Syng’s grave is the crypt of Syng’s grandson, Dr. Philip Syng Physick.

Dr. Physick, the noted “Father of American Surgery,” was a pioneer in surgical techniques and inventor of many surgical tools. He was an advocate of using autopsies as a means of education. He was one of the few doctors to treat victims of Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic in 1793. He insisted President Andrew Jackson stop smoking as a remedy for his lung hemorrhages. The city of Philadelphia honored his groundbreaking efforts by naming soda after him. But it’s really good soda.

Another doctor buried here is Thomas Bond.

Bond co-founded Pennsylvania Hospital and was an early proponent of morphine. His home on South 2nd Street has been converted to a bed & breakfast.

Yet another doctor at the cemetery is Dr. William Camac.

Medical practice aside, Camac was the founder of the Philadelphia Zoo, the oldest zoo in the country.

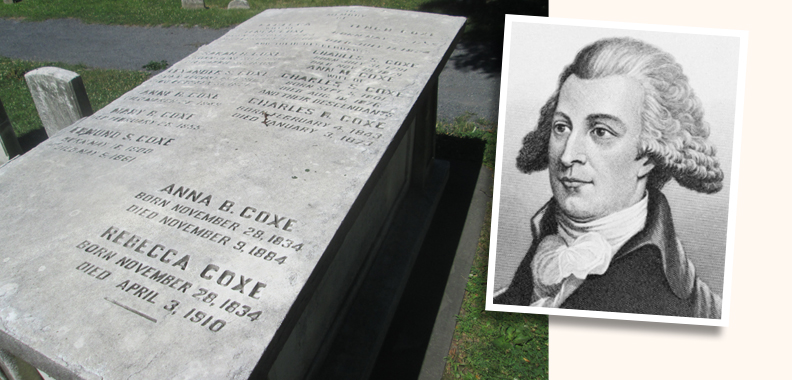

The grounds are also home to Tench Coxe and the whole Coxe family.

Tench was a delegate to the Continental Congress and an economist who wrote under the generic pseudonym “A Pennsylvanian.”

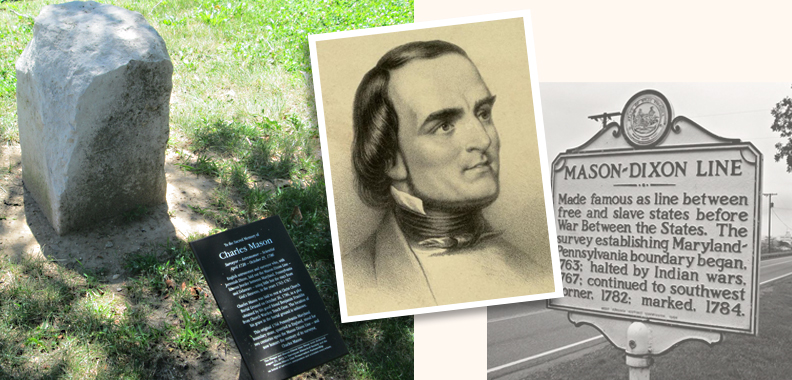

Nearby is the weather-worn grave marker of Charles Mason.

From 1763 to 1768, Charles Mason, along with fellow surveyor Jeremiah Dixon, plotted the physical border between Pennsylvania and Maryland, thus determining the North and the South. Of course, the nickname “Dixie” stems from Jeremiah’s surname. I don’t know why the North isn’t called “Masie.” (Except for that department store.)

Christ Church Burial Ground has made room to honor its own. Here is the grave of Peter Kurtz, Sr.

Peter served as church organist for 41 years.

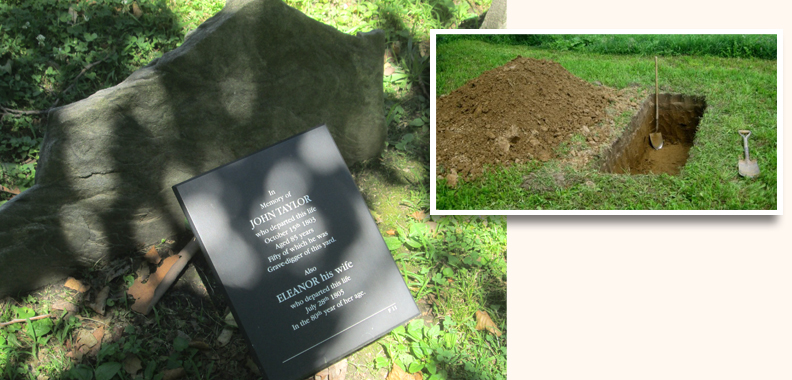

Sadly, John Taylor’s marker has suffered severe damage at the hands of the elements.

John was a gravedigger here at the cemetery for 50 years.

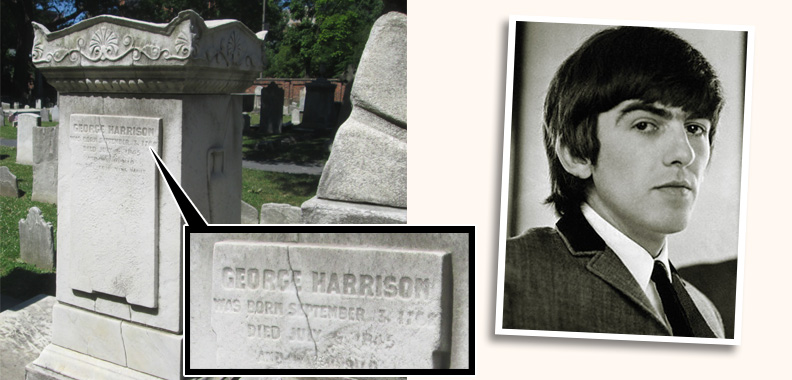

On my way out, I spotted one more famous grave.

Um…. it might not be the same one. (I was told that within the grounds are the remains of William Clinton, Julia Roberts and Ethel Mertz, but now were getting carried away.)

Just down the street from Christ Church Burial Ground is the famous residence of Elizabeth Griscom Claypoole, better known as Betsy Ross. When she was 24, she found work as an upholsterer and a seamstress repairing uniforms and making tents. She also stuffed musket balls into paper tubes for use in battle. She was married three times by the time she was 31. (Her first husband died in a gunpowder explosion, although that is debated. Her second husband died in a British prison where he was serving time for treason.) However, there is no archival evidence that the story of her designing the American flag is true. It was fabricated and promoted as a patriotic role model for young girls and a symbol of women’s contributions to American history. There is even some debate over whether or not she actually lived at the house that bears her name. The story seems to have worked, though, because everyone believes it. That, my friend, is terrific marketing. In case you insist on believing the story, here’s the grave of Betsy Ross. She’s buried in the courtyard of the Betsy Ross House… making up history daily, beginning at 10 AM.

Just down the street from Christ Church Burial Ground is the famous residence of Elizabeth Griscom Claypoole, better known as Betsy Ross. When she was 24, she found work as an upholsterer and a seamstress repairing uniforms and making tents. She also stuffed musket balls into paper tubes for use in battle. She was married three times by the time she was 31. (Her first husband died in a gunpowder explosion, although that is debated. Her second husband died in a British prison where he was serving time for treason.) However, there is no archival evidence that the story of her designing the American flag is true. It was fabricated and promoted as a patriotic role model for young girls and a symbol of women’s contributions to American history. There is even some debate over whether or not she actually lived at the house that bears her name. The story seems to have worked, though, because everyone believes it. That, my friend, is terrific marketing. In case you insist on believing the story, here’s the grave of Betsy Ross. She’s buried in the courtyard of the Betsy Ross House… making up history daily, beginning at 10 AM.

Well, I hope you enjoyed this little tour of history and I better not catch you cheating when I give the test.