The illustrationfriday.com current challenge is “wrapped”.

I actually did this drawing almost three years ago, waiting for the Illustration Friday word to be “wrapped”.

FINALLY!

IF: impatience

This week’s illustrationfriday.com challenge is “impatience”.

There was nobody that ever lived that was as impatient as my father.

Perhaps it started when he was a child. He and his parents lived at eight different addresses on West 52nd Street in Philadelphia. They kept moving up the block. My father told me it was because each time his father got a salary increase they would move to a bigger house. I think he just didn’t want to wait as long for the mail delivery.

My father never enjoyed a leisurely meal. When I was a kid, dinnertime was a race. My father devoured his daily evening repast in record time. My father would always be served first. As my mother was presenting my brother and me with our prepared platters, my father would be dragging a slice of bread around the rim of his plate, sopping up the last bits of crumbs and gravy. My father would be on his third cigarette, flicking the ashes into his plate, as we remaining three diners were just beginning our dinner. This rushed and impatient gluttony may have stemmed from my father’s military service. In January 1944, my father enlisted in the United States Navy. He was stationed on the battleship USS South Dakota on its second tour in the Pacific. My father’s meals were taken in the ship’s mess hall with hundreds of other sailors. He described the food distribution as an efficient assembly line where your metal tray was piled with meat, potatoes, corn, a scoop of ice cream and a pack of cigarettes thrown on top of it all. The men were given approximately twenty-two minutes to eat before they were to return to their assigned post. My father carried this mindset for accelerated food consumption for the rest of his life, each meal becoming an Olympic event in speed eating. (In addition to biting my fingernails and walking like a duck, I seemed to have inherited this trait from my father, too.)

My father refused to wait in line. For anything. Ever. If we, as a family, went out for a special occasion, my father would pass on any restaurant where he couldn’t get immediate seating. My mom would sometimes be successful in persuading him to give a hostess our name for inclusion on a waiting list for a table, but after one or two minutes, we would invariably leave. We’d walk, silent and embarrassed, to the car as my father grumbled under his breath. We’d drive by several more restaurants in Northeast Philadelphia, seeing patient people patiently waiting for a table, patiently. My father would curse them and we would end up at The Heritage Diner, my father’s favorite eatery unless there was a line. For years, my family would joke, wondering if our name was ever called for a table at the Open Hearth restaurant at Holme Circle, after we walked out because my father wouldn’t wait.

My father always wore a watch, but I don’t believe he could tell time. If my brother or I had an appointment to go to, my father would begin reminding us five or six hours prior. If it was an early morning appointment, he would wake up early, point to his watch and scream to us upstairs, “Get up! Get up! Don’t you have to be somewhere at 11:30? It’s almost 10 o’clock!” At my father’s anxious alert, we would scramble out of bed, and rush to the shower in a panic, assuming we were going to be late. In our frenzy, we’d catch a glimpse of our bedroom clock showing the time to be 7 AM. My father was not happy seeing anyone asleep. If he was awake, everyone must be awake.

When I was nineteen, I went to Walt Disney World with three of my friends. When I returned home, I excitedly told my parents about the wonderful time I had. I urged them to visit the theme park themselves. Then I tried to imagine my father being there. He would refuse to wait in line for any ride, attraction, show performance or restaurant. (If you have ever been to a Disney theme park, you will know that the time spent there includes a certain amount of waiting in line.) He would return home, angry and complaining, “I don’t know what the big deal is about that place. We didn’t get to see a goddamn thing! I wasn’t gonna wait in line to ride some goddamn flying elephants!” I reconsidered my urging.

When my father died, my wife took the daunting task of cleaning and emptying his house in preparation for sale. She emptied closets and drawers, packaged clothing for charity contribution and gathered unwanted items for disposal. One day, she opened one of my father’s dresser drawers and discovered dozens and dozens and dozens of unused wallets, some still in department store packaging adorned with price tags. With my father not around to question, we surmised he never wanted to wait in line to buy a new wallet when the time came to replace his current one.

Comments

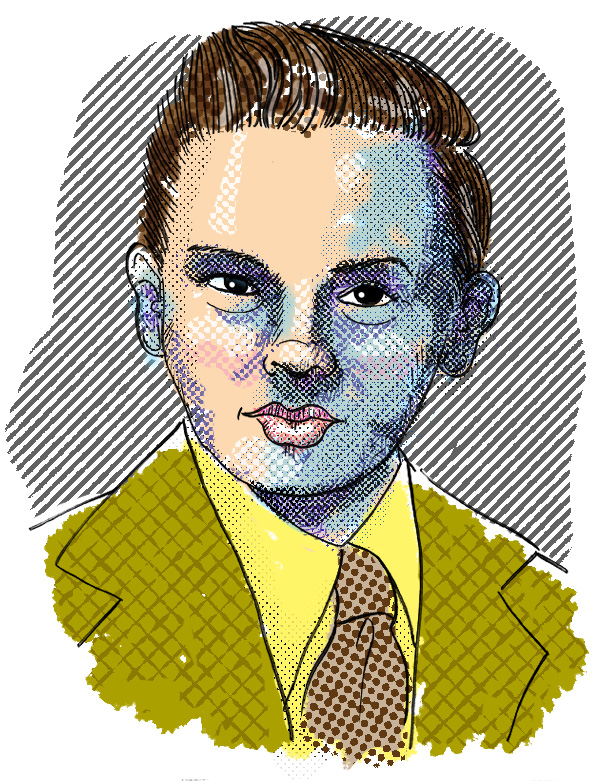

DCS: bobby driscoll

Bobby Driscoll was Walt Disney’s Golden Child. He was the typical cute, scrappy All-American boy and Disney Studios milked that image for all they could. Bobby starred in a string of classic live-action pictures for Disney, including Song of the South, So Dear to My Heart and Treasure Island. He was also provided the voice for “Goofy Jr” in several animated short subjects. Bobby’s most famous Disney role was providing the voice of the title character in the 1953 animated classic Peter Pan. Bobby was in high demand and Disney allowed the young star to be “loaned out” to other studios, which was common practice for contracted performers. Bobby won an Oscar in 1950 for “Best Juvenile Actor.” (That category was discontinued by the Academy in 1960.)

As Bobby grew older, he didn’t quite fit the persona of the “likable kid” anymore. He grew dissatisfied with that image. He also developed terrible acne. He would make public appearances with heavy, concealing makeup. Disney seized this opportunity to sever Bobby’s contract, essentially abandoning him.

He found his demand dwindling in the early to middle 1950s. He took small, one-shot roles on episodic television, usually playing a bully or gang member. He was arrested for marijuana possession in 1956. In 1961, he was arrested and sentenced for disturbing the peace, assault and drug charges.

After his release from prison and and a year after his parole expired, Bobby moved to New York City. He became part of Andy Warhol‘s Greenwich Village art community known as The Factory, where he began focusing on his artistic talents. He took one more acting role in an experimental film called Dirt in 1965.

Bobby soon afterward left Warhol and The Factory and disappeared, penniless. On March 30, 1968, two boys playing in a deserted East Village tenement found his dead body. The medical examination determined that he had died from heart failure caused by an advanced hardening of the arteries due to longtime drug abuse. There was no ID on the body, and photos taken of it and shown around the neighborhood yielded no positive identification. When Bobby’s body went unclaimed, he was buried in an unmarked grave in New York City’s Potter’s Field. Nineteen months after his death, Bobby’s mother sought the help of the Disney Studios to contact him for a reunion with his father, who was near death. Given his last know whereabouts, she contacted the New York City Police who, based on a fingerprint match, directed her to the pauper’s graveyard.

Comments

Monday Artday: ghost

What started out as a black and white sketch of a crooked street leading to a peaceful graveyard, with a run-down manor perched high on a hill that loomed over Main Street evolved into one of the greatest and most beloved attractions in Disneyland — The Haunted Mansion.

A short time after the opening of Disneyland in 1955, Walt Disney asked Imagineer Ken Anderson to elaborate on the original drawing and create a story for a future”haunted” attraction. Ken eventually presented Walt with a sketch of a run-down antebellum plantation house, boarded-up and overgrown with trees and weeds. Walt frowned upon the drawing, saying he would not have such a dilapidated building in his clean park. “We’ll take care of the outside,” he famously said, “The ghosts can have the inside.”

Between Ken’s stories of mysterious a sea captain, spectral wedding parties and ghostly families and Walt’s fascination with San Jose’s Winchester Mystery House, the Haunted Mansion attraction was beginning to take shape. Many concepts were considered including a wax museum, a “Museum of the Weird” restaurant, even a walk-through attraction. A ride-through was settled on and under Ken Anderson’s appointment, Imagineers Rolly Crump and Yale Gracey were given the task of creating the Mansion’s special effects. Their workshop was filled with creepy gags and spooky props. They kept the effects wired to a master switch that was motion-activated. At the end of the work day, they would leave and, later, the studio cleaning crew would proceed on their nightly duties. One morning, Crump and Gracey were informed that they would have to clean their own studio, as the custodial staff has tripped the motion sensor and were frightened out of the away.

Construction was completed on the Haunted Mansion structure in 1963, but due to Disney’s involvement in the 1964 New York Worlds Fair, the building sat untouched for six years, despite advertisements and signage for the attraction. Walt Disney’s death in 1966 was followed by an interior redesign of the show area. On August 9, 1969, Disney’s Haunted Mansion opened. The opening brought in record crowds and has remained one of the most popular attractions for everyone living and dead.

Disney’s Haunted Mansion has a cult following. There are thousands of loyal and devoted fans. There are dozens of websites (including the excellent Doombuggies.com) that chronicle the history, secrets and updates to the attraction. The annual unofficial Disney celebration “Bats Day in the Fun Park” caps off the day’s activities with a group ride through The Haunted Mansion, with participants numbering over fifteen hundred.

And then there are the ones who wish to make The Haunted Mansion their eternal home. Since the 1990s, several people have attempted to fulfill a deceased loved one’s last wish to become a permanent resident of The Haunted Mansion. Cast Members (Disney employees) have spotted riders on the surveillance cameras sprinkling cremated remains alongside the ride vehicle (affectionately called “Doom Buggies“) track. When a Haunted Mansion Cast Member sees ashes being spread from a passing Doom Buggy, the attraction is shut down for hours while the custodial department comes in and begins the clean up. Disneyland’s custodial department had to purchase special vacuums with very sophisticated HEPA filters that can capture the gritty ash of human remains while also capturing the small bone fragments are usually present after cremation. When the “Ghost Host“, the on-vehicle ride narrator, announces that the Mansion is home to “999 happy haunts” and informs guests that there is room for a thousand, I believe he is kidding.

Comments

from my sketchbook: ub iwerks

In 1919, eighteen year-old Ub Iwerks was working for the Pesman Art Studio in Kansas City, Missouri. It was here he met another eighteen year-old, a fellow artist named Walt Disney, who would become his oldest and best friend. Disney and Iwerks moved on to work as illustrators for The Kansas City Film Ad Company. While working for the Kansas City Film Ad Company, Disney became interested in animation and Iwerks soon joined him.

In 1922, Disney began his Laugh-O-Gram cartoon series and Iwerks joined him as chief animator. In 1923, Iwerks followed Disney in his move to Los Angeles to work on a new series of cartoons. Disney asked Iwerks to come up with a new character. The character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, was animated entirely by Iwerks. Following the first cartoon, Oswald was redesigned on the insistence of Disney’s distributor, Universal Studios. Universal took full ownership of Oswald and eventually replaced Disney and Iwerks, handing the character over to Walter Lantz (who would later create Woody Woodpecker).

In 1928, Disney asked Iwerks to start drawing up new character ideas. Iwerks tried sketches of frogs, dogs, and cats, but none of these appealed to Disney. Iwerks was soon inspired by a drawing of Walt Disney done by fellow animator Hugh Harman. Harman drew some cartoony mice around a photograph of Walt Disney. Iwerks made some sketches and created a little mouse character. Walt approved, first naming the character “Mortimer”, and eventually “Mickey”.

Unhappy with Disney’s harsh command and a feeling he wasn’t getting proper credit, Iwerks left Disney and opened his own studio in 1930. Unable to match the success of other studios, especially that of his former employer, Iwerks returned to The Disney Studios in 1940. Upon his return, he worked mostly in the development of visual effects. Iwerks is credited with developing the process for combining live action and animation used in Song of the South as well as the xerographic process adapted for cel animation used in One Hundred and One Dalmatians. He also worked at Walt Disney Imagineering, helping to develop many Disney theme park attractions during the 1960s. Iwerks did special effects work outside the studio as well, including his Academy Award nominated achievement for Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds.

Iwerks was known for his fast work at drawing and animation and his wacky sense of humor. Warner Brothers animator Chuck Jones, who worked for Iwerks’ studio in his youth, said “Iwerks” is Screwy spelled backwards. Iwerks died of a heart attack in 1971.

Walt Disney is still credited with the creation of Mickey Mouse.

Comments

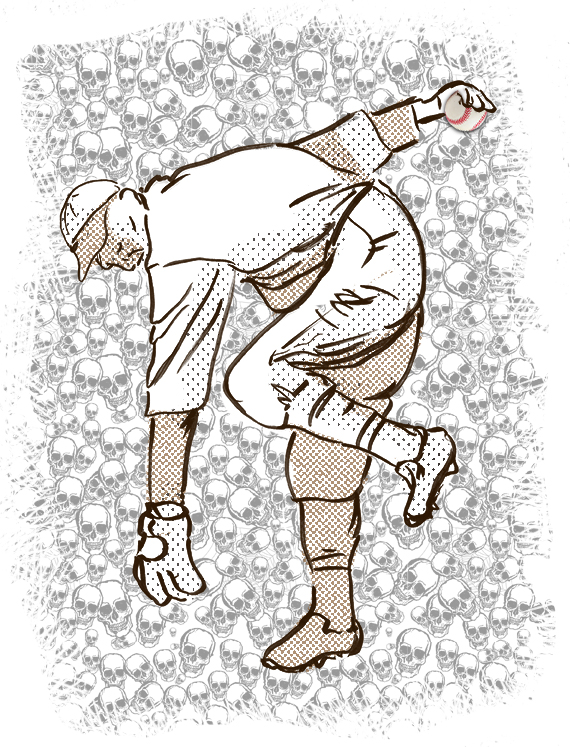

DCS: carl mays

Ray Chapman was born in Beaver Dam, Kentucky in 1891. Ten months later and 150 miles away the man who would kill him was born.

Ray was an above-average shortstop playing with the Cleveland Indians in the early twentieth century. He led the league in several hitting and fielding categories. He batted .300 in three seasons and is 6th on the all-time list for sacrifice hits.

To his New York Yankee teammates, Carl Mays was a son-of-a-bitch. He was a mean, belligerent, complaining loner who had the disposition of a man with a constant toothache. He was, however, a master of deceptive pitching. In the early days of organized baseball, aside from the basics, there were few rules to be followed. This allowed for baseballs to be scuffed, scraped, sandpapered, spat upon, and cut by pitchers. Coupled with the fact that one baseball usually lasted an entire game, hitting, and even seeing, a ball was extremely difficult for batters. In addition to the physical augmentations Mays used on the ball, he earned himself the nickname “Sub” because of his underhand, “submarine”-style of pitch delivery.

On August 16, 1920, in a game at New York’s Polo Grounds between the Yankees and the Indians, Ray Chapman stepped to the plate in the fifth inning. Mays went into his wind-up and threw with his regular submarine delivery. The pitch was high and tight and Chapman never moved out of the way, unable to see the ball. Mays heard the ball crack and it was immediately returned to him at the pitcher’s mound. Mays assumed the ball hit Chapman’s bat, so he routinely tossed the ball to first base for the out. The “crack” was actually the sound of the ball penetrating Chapman’s skull. Chapman was rushed to a New York hospital where he died twelve hours later, after surgery.

This incident forced Major League Baseball to modify some of its rules. The spitball was officially banned. Dirty, scuffed or otherwise defaced baseballs are regularly replaced by umpires. Batters are now required to wear batting helmets. The submarine pitch, however baffling, is still legal.

Comments

IMT: holes

The ispirational word this week on the InspireMeThursday website is “holes”.

“There’s nothing wrong with you that a gaping hole drilled into your skull under unsanitary conditions couldn’t cure.”

Trepanation. An innocent enough sounding term.

Trepanation is an antiquated and misguided medical procedure in which a hole is drilled into the human skull, thus exposing the meningeal layers surrounding the brain in order to treat health problems related to intracranial diseases. Evidence of trepanation has been found in prehistoric human remains and in civilizations all over the world.

In modern times, trepanation is used for epidural and subdural hematomas, and for surgical access for certain other neurosurgical procedures, such as intracranial pressure monitoring. Modern surgeons generally use the term craniotomy for this procedure. The removed piece of skull is typically replaced as soon as possible.

The practice of trepanation for other purported medical benefits continues has developed a small cult following. This movement was furthered by the writings of Bart Huges, a self-proclaimed “expert” on the subject of trepanation, although he did not complete his medical degree. Hughes claims that trepanation increases “brain blood volume” and thereby enhances cerebral metabolism.

Heroes among the supporters of trepanation are Joey Mellen and Amanda Fileding. Mellen and Fielding made two attempts at trepanning Mellen. The second attempt ended up with Mellen in the hospital, where he was sent for psychiatric evaluation. When he finally returned home, Mellen decided to try again. Amanda Fielding performed self-trepanation, while Mellen filmed the operation. Fielding stood before a mirror and pierced her skull with a common power dill. With her head wrapped in gauze and a blood-soaked smile on her face, she offered the play-by-play of her procedure, eventually closed the wound and, several hours later, accompanied Mellen to a restaurant for dinner. She never lost consciousness.

Comments

Monday Artday: film noir

The Monday Artday challenge this week is “film noir”.

“Would you like me to tell you the little story of right-hand/left-hand? The story of good and evil? H-A-T-E! It was with this left hand that old brother Cain struck the blow that laid his brother low. L-O-V-E! You see these fingers, dear hearts? These fingers has veins that run straight to the soul of man. The right hand, friends, the hand of love. Now watch, and I’ll show you the story of life. Those fingers, dear hearts, is always a-warring and a-tugging, one agin t’other. Now watch ’em! Old brother left hand, left hand he’s a fighting, and it looks like love’s a goner. But wait a minute! Hot dog, love’s a winning! Yessirree! It’s love that’s won, and old left hand hate is down for the count!”

Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) in “The Night of the Hunter”

Oscar-winning actor Charles Laughton directed one film in his career 1955’s “The Night of the Hunter”. It starred Shelley Winters, Lillian Gish, a very young Peter Graves and Robert Mitchum in a positively chilling performance as one of the most fearsome villains in movie history. Mitchum plays self-appointed Reverend Harry Powell, a fanatically-religious serial killer. He preys on the widow and children of his prison cellmate. He gives a riveting portrayal that shows the character as calm as he is menacing. The character was based on real-life killer Harry Powers and was the inspiration for a number of “tough guys” to get “LOVE” and “HATE” tattooed across their knuckles.

Laughton chose to shoot the film in black and white, paying homage to the harsh, angular look of German expressionist films of the 1920s. The film is starkly lit, strangely staged and, in parts, cryptically scripted. The result is a fable that seems to take place in a surreal world.

Interestingly, Laughton openly disliked children. “The Night of the Hunter” was an odd choice of story for him to direct considering the protagonists are 12 year-old John (Billy Chapin, Father Knows Best‘s Lauren‘s brother) and 7 year-old Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce, who never appeared in another film). Refusing to work with them, Laughton had Mitchum direct the scenes in which the children appeared. This, too, was odd, as Mitchum’s sadistic character terrorizes the children throughout the movie.

Comments

IF: idle

The illustration friday challenge word this week is “idle”.

“Idle hands are the Devil’s Playground.”

Actually, this is the Devil’s Playground.

Comments

Monday Artday: astronaut

The current challenge on Monday Artday is “astronaut”.

This illustration is based on this short story by this guy…

Your dub is dead, theres something wrong

The cosmic winds shifted, and the Hera probe battered about its tract of outer space. Inside, the two men in their heavy suits gripped the hand rests on their specially-designed seats as a wave of bad omens reverberated through the shell that surrounded them. Warren Bargeld, whose belly was just barely restrained by his protective outfit, signaled to his svelte partner, Corey Williams, to activate their communication link. Williams flicked a series of switches back and forth, and made a face. He turned back to Bargeld with raised eyebrows and shrugged his shoulders. Bargeld said something that Williams didn’t hear. In fact, neither man could hear anything outside of the whooshing of fluid in their respective ears. With verbal communication impossible, Bargeld reached for the pen that, while firmly tethered to a chain around his wrist, was floating freely in the starlit cabin. Scribbling something down on a piece of corn-fiber paper (good for note-taking and palate-cleansing), Bargeld struggled to finesse the implement with his gloved hands.

Now what?

Now what, indeed. Or, at least thats what Williams would have said. Without their communication link, one of the two of them may have just as well stayed back on Earth. Interrupting Williams thoughts was a blast of light from a monitor that sat between the two men. The static-stricken screen settled on an image of Marcus Mell in his finest blast-off shirt and moustache. A headset wrapped around his comb-over, Mell barked orders and cries of concern, all of which went seen but unheard by the spacemen. Looking at each other, and then at the screen, Williams and Bargeld shrugged their shoulders in unison; a synchronized white flag routine. Not grasping what was wrong, Mell continued to shout into his microphone, leading the men around him in the command center to plug their ears with their fingers. One such ear-plugger tapped Mell on the shoulder and explained how the Heras turbulent takeoff had disabled their communication link. Mell stood silent for a moment, his mind racing to think of a solution before anyone else did. Bargeld waved his think paw as frantically as he could at the camera. It finally caught Mells attention, but Bargeld and Williams were miming to each other. Squinting through his massive glasses, Mell tried to make out from the fuzzy visual feed just what those men were up to.

Bargeld pointed at Williams. Williams pointed at himself with a look of surprise and shook his head from side to side. Bargeld clasped his giant hands together, silently pleading for his partner to go. With a slight fogging of his visor, Williams detached the elaborate series of harnesses that secured him to his post. Jaunting back and forth in a walk that was more of a bounding waltz, Williams strode toward the airlock, affixed a canvas rope to his suit, and opened the first door. Once that door was securely shut, Williams opened the outer door and stepped out into the nothingness. Drifting around the side of the craft, Williams gazed into the void of the universe. Even if he could hear anything (the noise of his air supply tube created an unending cathartic howl), there was nothing he could say that would be worth hearing. Using the handrails conveniently installed around the hull of the probe, Williams inched himself over to the area of impact. Though they didn’t sustain any serious injuries, Williams and Bargeld were shaken loose of their seats grips when whatever hit the Hera hit the Hera. As Williams surveyed the damage, a pattern emerged from the blackened carcass of the craft. Fearing his tether to be short and his air supply shorter, Williams forwent further examination and return to the airlock.

Back inside, Williams gestured to the remote camera, which Bargeld deployed without knowing what to look for. Like lovers guiding each other on a pottery wheel, Williams and Bargeld maneuvered the camera to read the one-word claim that had been emblazoned across their lowly vessel. Together they mouthed its horrendous syllable:

MINE.