This week’s Illustration Friday challenge word is “suspense”.

Alfred Hitchcock – Hollywood’s master of suspense. He was a technical innovator, a masterful storyteller and a visionary director. In his career, that spanned six decades, he never won an Oscar (aside from an honorary and conciliatory lifetime achievement award).

Monday Artday: rain

The new challenge word on the Monday Artday illustration blog is “rain”.

Let the stormy clouds chase

Ev’ryone from the place

Come on with the rain

I’ve a smile on my face

Comments

Monday Artday: daily chores

After a long, long hiatus, the illustration showcase website Monday Artday is back with a vengeance! The first challenge, in nearly seven months, is “daily chores”.

He didn’t mind the “Fee-ing” and the “Fi-ing” and the “Foe-ing” and the “Fum-ing”, but the Beanstalk Giant couldn’t stand grinding the bones to make his bread.

Comments

from my sketchbook: alexa kenin

Alexa Kenin began acting as a child, landing her first role opposite Academy Award-winning actor Jason Robards in the 1972 TV movie The House Without a Christmas Tree. She appeared in several more TV productions, including five Afterschool Specials.

The 80s brought Alexa her big-screen debut in the Tatum O’Neal-Kristy MacNichol teen camp film Little Darlings. After more guest roles on episodic television, Alexa found herself in a supporting role alongside Clint Eastwood in Honkytonk Man in 1982.

Soon, Alexa was cast in her most-remembered role as Jenna in Pretty in Pink with Molly Ringwald. Just after Pretty in Pink wrapped production, 23-year-old Alexa was found dead in her Manhattan apartment. Although still officially classified as an unsolved crime, the belief is that she was murdered by a jealous ex-boyfriend.

Comments

IF: forward

When my parents gave me my first box of crayons and a blank drawing pad, they had no idea I would turn it into a career. I majored in art in high school and attended a vocational art school after spending a year in the retail world and realizing that I was better suited for a more creative profession. After earning my degree, I became the art director for a small chain of ice cream stores in the Philadelphia area. This was a great opportunity for a young graduate and I was anxious to let my imagination and school-acquired skills loose on the world. After a year, the company eliminated their in-house art department (of which I was the sole member) and I was out of a job. I soon began the gruelling course of a freelance artist. I filled-in at a few production houses* doing paste-up for newspapers and other various publications. In between jobs, I concentrated my efforts on finding full-time employment, as I was newly-married with a child on the way. I checked the “Help Wanted” section of the newspaper on a daily basis, but the “artist” listings were usually short and limited to painter’s assistant jobs and counter help at quick-copy service stores. I maintained contact with some classmates and my art school’s placement office for job leads, but the pickings were slim.

One morning, I circled an ad in the Philadelphia Inquirer. It seemed an ad agency on the prestigious Main Line section of suburban Philadelphia was seeking an artist/designer. I called the number and spoke briefly to a female voice who made arrangements for me to come in for an interview this upcoming Saturday evening. I thought it was an odd day and time for an interview, but who was I to question? I needed a job. With only one car, my wife drove me and my small portfolio of printed samples of my work out to – what would hopefully be – my new job location.

After consulting a map (remember, this was the days before the Internet and the GPS), we navigated the streets. Surprisingly, we arrived in a residential neighborhood, not an office building as I had expected. Checking the address again, we pulled up to the curb in front of a modest house surrounded by other similar-looking houses. I, in my suit and tie, walked up to the front door and rang the door bell. I half-expected that I was at the wrong location, but when an expressionless woman opened the door and greeted me with “You must be Josh,” I knew this must be the place. I entered her home and was directed to the dining room table. The woman introduced herself as Zimra Chorney – slightly older than I with unkempt, curly hair and clipped, bird-like features – and asked to see my portfolio. I had been on many interviews since my recent entry into the art business, but most (if not all) had been conducted in an office or a working design studio. I unzipped my small leather case and opened it to face my inquisitor. Silently, she turned the protective plastic pages of newspaper ads, ice cream promotional flyers and the occasional illustration. She examined my work through squinted, judgemental eyes set in her vacant face. Zimra reached the final page and closed the back cover. She then turned to a shelf and removed several folded pieces of solid-colored card stock. Her claw-like hands opened one of the folded pieces to reveal a black-and -white printed advertisement for, what appeared to be, a bakery.

“This,” Zimra began, “is the sort of promotional work we do.” and she gently tossed a few similar pieces in my direction. (“We,” I thought as I cautiously looked around, “Who is ‘we’ “? ) I opened one of the cards and skimmed the content. The outside of the brochure was solid, glossy magenta with no type or art whatsoever. Inside, it was very wordy with some small illustrations of birthday cakes and cupcakes spaced throughout, failing in their attempt to comfortably break up the over-abundance of descriptive text. I could tell the other brochures that I left unopened on the table were similar, the outside color being the only variance. I feigned a smile at the brochures and nodded, but offered no comment or criticism. That was good, because Zimra had plenty to say in the criticism department.

She stood across the table from me and expounded on the lack of professionalism of my work. She explained that my work was weak and of poor quality and content. She displayed one of her brochures, looked lovingly at the piece and, injecting a haughty tone into her speech, said “This is more along the lines of the type of high-quality and professionalism we seek and expect.” As she spoke, she caressed the folds of the brochure and ran her bony fingers along the glossy ink of the cover.

“In a few years, if your talent and abilities are more developed, we may be interested.,” she said, using the royal “we” once again. Zimra escorted me to the door and showed me out. I don’t even remember walking down to my car. My wife asked how things went and, by the bewildered look on my face, her question was answered.

Jumping forward a few years, I had produced a body of work of which I was quite proud. I had redesigned the mastheads of several newspapers and magazines. I had created adverting pieces for such varied companies as Motorola, Holiday Inn, an East coast chain of turnpike rest stops and some major area department stores. I worked closely with an advertising agency, where I single-handedly designed and produced an annual plumbing supply catalog. I briefly entered the publishing industry, where I maintained a roster of no less than twenty-five newsletters and dozens of books. I ran the creative end of a real estate ad agency. I returned to the world of retail advertising and became the art director for a local chain of carpet and flooring stores whose headquarters was on the Main Line.

One day, on my way to work, I stopped for coffee at a Wawa convenience store on Montgomery Avenue. (Wawa is a very popular spot in the Philadelphia area for a quick bite, great coffee and that forgotten quart of milk or loaf of bread on your way home. And it’s much cleaner and friendlier than 7-11.) The coffee service area was bustling and crowded, as is normal for a workday morning at Wawa. I filled a 20 ounce cup with java, cream and one Sweet ‘n Low. I dodged a female employee who was wiping up a spill at the counter with a dingy, gray rag. As I made my way to the checkout to pay for my purchase, the same female employee jumped behind a cash register to help handle to overflow of customers. She wore the standard Wawa-issued visor to corral her unkempt, curly hair. The dark brown of her apron could not adequately hide the stains that peppered the front of the garment. She looked familiar, too. The name badge affixed to her apron’s shoulder strap was emblazoned with “ZIMRA” in big. black letters.

As the customers before me, one-by-one, paid for their selections, I fixed my gaze on the woman who once belittled me for my lack of talent and professionalism. This woman, who just a few short years ago insulted the quality of my work, was now wearing a dirty apron, sopping up spilled coffee and running a cash register in a convenience store. The last time I held a job in the same range as this, I was eighteen years old.

My turn to pay had come and I happily tendered a buck to Zimra – who didn’t acknowledge me, just as she didn’t acknowledge me those many years earlier.

I walked out of that Wawa and I never saw Zimra Chorney again. My career as a professional artist has continued to flourish and I have learned, grown and improved with each subsequent job I have taken. My initial meeting with Zimra taught me a lesson, but not the lesson she wanted to teach. My second meeting taught me more. Do I ever wonder what ever became of Zimra Chorney? Honestly, I don’t give a shit.

* In the days before computers, desktop publishing and the Internet, printed materials – such as newspapers, books, and brochures – were produced and assembled by hand, in a tedious, time-consuming process called “paste-up” that involved X-acto knifes, heated adhesive wax, typeset galleys, rulers, border tape and non-reproductive blue pens.

Comments

from my sketchbook: beryl wallace

Teenage aspiring dancer Beryl Heischuber answered a casting call ad and landed a role in the 1928 production of Vanities at the Earl Carroll Broadway theatre. Using the more accessible (and more pronounceable) name “Wallace”, Beryl appeared amid dozens of other young dancers billed under the umbrella title “the most beautiful girls in the world”. She performed in six more variations of Vanities at Earl Carroll’s venue, most notable for their risqué premises, scantily costumed females and full nudity for the first time on Broadway.

Beryl began a relationship with theatre owner Earl Carroll, who was 16 years her senior. When Carroll opened his Hollywood location of the Earl Carroll Theatre on Sunset Boulevard in 1938, the building’s facade boasted a 20-foot high portrait of Beryl in neon. Beryl was featured in small roles in several “B” Westerns with co-stars like Tom Keene and Roy Rogers, but her primary job was star performer at Earl Carroll’s Theatre.

On June 17, 1948, Beryl and Earl Carroll were aboard United Airlines Flight 624 from New York City to Los Angeles when the flight crew received warning of a fire in the cargo hold. Although it turned out to be a false alarm, procedure dictated that CO2 be released into the area to extinguish the flames. However, relief valves were not opened and carbon dioxide seeped back into the cockpit, incapacitating the crew. The aircraft was put into an emergency descent. It struck a high voltage power line, burst into flames and crashed into a wooded hillside near Aristes, Pennsylvania. All 39 passengers, including Beryl Wallace and Earl Carroll, were killed.

The Earl Carroll Theatre continued operation after its founder’s death. In the 1950’s, it fell on hard times and was purchased and re-opened as The Moulin Rouge nightclub. Later, the TV game show Queen for a Day was broadcast from the theatre during its nine-year run. Once again, the venue changed hands and became the Hullaballoo Rock and Roll Club, capitalizing on its popular TV namesake. In the 1960s, it was renamed “The Aquarius Theatre” and was home to the long-running musical Hair during its West Coast run. The Doors even performed there in 1969. In the 80s, the theatre served as the studio for nine seasons of Star Search and for many Jerry Lewis Telethons. In the early 90s, it was once again renamed, this time “The Chevy Chase Theatre” for five weeks, until the comedian’s disastrous talk show was canceled. More recently, the location is known as “Nickelodeon on Sunset” and is the filming location for current shows* like iCarly and Victorious, as well as past favorites like All That and Drake & Josh. Although a reproduction is displayed at Universal Hollywood’s CityWalk, the original neon portrait of Beryl Wallace vanished decades ago.

* No new shows have been filmed here since 2017 and all Nickelodeon signage has been removed from the building. Rumors about its future usage have included possible tenants James Corden and Bill Maher.

Comments

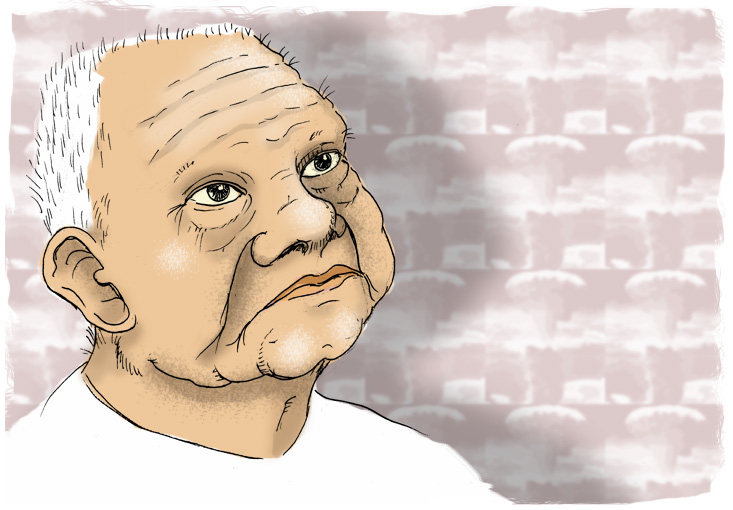

from my sketchbook: tsutomu yamaguchi

Tsutomu Yamaguchi worked as a draftsman designing oil tankers for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Nagasaki. Japanese industry was suffering as a result of World War II. Resources and materials grew more and more difficult to come by. Tsutomu, like many Japanese, felt Japan should have never started a war. He became despondent over his homeland’s situation and considered secretly poisoning his family if Japan was not victorious at the war’s end.

In 1945, 29-year old Tsutomu went on a three-month business trip to Hiroshima for his employer. On August 6, he and two colleagues were preparing to return to Nagasaki when Tsutomu realized he had forgotten his hanko (a printing stamp used instead of a signature to authorize documents in most Asian countries). As Tsutomu hurried back to his workplace to retrieve his stamp, American bomber Enola Gay was dropping an atomic bomb on the center of Hiroshima just under two miles away. There was a great flash and the subsequent explosion ruptured Tsutomu’s eardrums, burned him on the left side of his body and left him temporarily blind. He crawled to shelter and, after resting for a bit, set out to find his colleagues. He was happy to find that they, too, had survived and the three spent the night in an air-raid shelter where they received proper medical attention. They returned to Nagasaki the following day. Tsutomu was given additional treatment. Despite being heavily bandaged, he returned to work on August 9th.

At 11 am, while Tsutomu was describing the horrific ordeal he experienced in Hiroshima to his supervisor, American bomber Bockscar dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki, just under two miles from Tsutomu’s workplace. This time, Tsutomu was unharmed in the explosion. His bandages, however, were damaged and contaminated. In the following days, he suffered a high fever from infection.

In later years, Tsutomu became a vocal opponent to nuclear arms, actively campaigning for disarmament. He participated in a documentary about nijū hibakusha (double atomic bomb survivors). Although there were approximately 165 claims of double atomic-bomb survival, Tsutomu is the only one officially recognized by the Japanese government.

Although he lost his hearing in one ear, Tsutomu led a relatively healthy life. He experienced health issues much later in life and eventually succumbed to stomach cancer in 2010 at the age of 93.

Comments

IF: twirl

For as long as he could remember, Tommy Lasorda, the longest tenured employee with the Dodgers organization, including twenty years as team manager, loved baseball. Growing up in a poor family in Norristown, Pennsylvania, Tommy could never afford to attend to a real Major League baseball game. When he was fifteen, Tommy joined his high school’s student crossing guard squad, but he had an ulterior motive. Tommy knew that at the end of the school year, the nuns would take the crossing guards to a Phillies game in neighboring Philadelphia in appreciation of service.

On the big day, the Phillies were playing the New York Giants and an excited Tommy Lasorda was beside himself with joy. After the game, he waited patiently by the clubhouse access tunnel at Shibe Park hoping to actually meet one of the ballplayers. One of the Giants outfielder lumbered past the star-struck youngster. “Can I get an autograph, please?”, asked Tommy. The player, Buster Maynard, riding high on the best season of what would be a short career, glanced at Tommy and barked, “Get the hell outta my way!” Tommy checked his line-up card to identify the player by uniform number as he walked into the opposing team locker room. Tommy was crushed and humiliated.

Seven years later, Tommy Lasorda, now a twenty-two year-old pitcher for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ minor league team in North Carolina, was on the mound facing the Single A division Augusta Yankees. He quickly struck out the first two batters of the inning, when he was frozen by the name being announced over the small ballpark’s public address system. Lasorda narrowed his eyes and watched as Buster Maynard now an aging bench-warmer hoping for one last shot at reviving his career ambled out of the dugout and approached the plate. The old man took a few creaky practice swings and stepped into the batter’s box. Lasorda silently fumed and went into his wind-up. He let the ball fly, rocketing just inches from Maynard’s chin and twirling the old man around in an effort to dodge the leather-clad projectile. Maynard took off his cap, scratched his head and peered across the field at the pitcher. Lasorda shot another head-high bullet at Maynard, this time forcing the elder player to hit the dirt in order to avoid getting some unrequested rhinoplasty. The third pitch from Lasorda wasn’t so forgiving. Maynard took one in the ribs and was awarded first base for his trouble.

After the game, the fading big-leaguer caught up with the young pitcher. “Hey kid,” Maynard began,”What the hell? Why were you throwing at me? I don’t even know you?”

Lasorda answered, “When I was a kid, I asked you for an autograph and you pushed me aside, you lousy son-of-a-bitch!” Maynard was dumbfounded and he shook his head in disbelief as Lasorda walked away.

During his years as a Major League manager, Tommy Lasorda always reminded his players to happily sign autographs, adding “Because you never know if, one day, one of those kids’ll knock you on your ass!”

Comments

from my sketchbook: tom forman

Tom Forman was a prolific “triple threat” in the early days of Hollywood. He was an actor in over 50 films beginning in 1913. He wrote seven screenplays and he was a sought-after director, calling the shots on over twenty-seven films. He directed top stars of the day including Lon Chaney and Mary Astor.

In November 1926, Tom was scheduled to direct the Columbia production of The Wreck. The night before filming was set to begin, Tom shot himself through the heart. He left no explanation. Tom was 33 years old.

Comments

IF: prepare

This week’s Illustration Friday word is “prepare.”

“Artie is a singer, and I’m a writer and a player and a singer. We didn’t work together on a creative level and prepare the songs. I did that.” Paul Simon

I understand the popularity of Simon and Garfunkel. I am aware of Paul Simon’s songwriting ability and his contributions to his success with one-time partner Art, and as a solo artist. I fully appreciate the longevity of his career…

… but, Jeez! Paul, that doesn’t give you the right to be a dick.