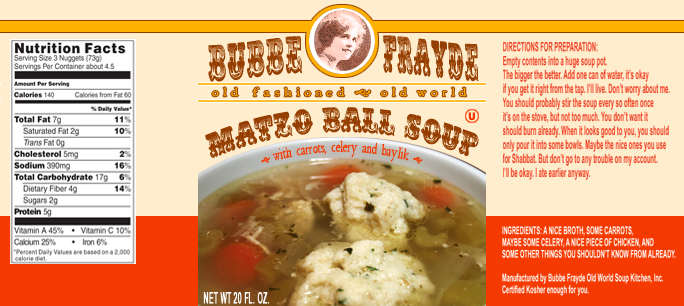

The inspirational word this week on Inspire Me Thursday is “label”.

Someday, maybe I’ll go into business with my mother-in-law.

from my sketchbook: hope summers

Hope Summers made her Hollywood debut at the age of fifty, beginning a career of playing essentially the same character. Hope was the older, genteel neighbor in countless Westerns, sitcoms and medical shows in the early days of television. She was featured as Hattie Denton, the friendly and helpful proprietor of the North Fork general store, in The Rifleman with Chuck Connors and she provided the voice of Mrs. Butterworth, the talking syrup bottle. But, Hope was best remembered as Aunt Bee’s slightly competitive, slightly gossipy best friend Clara Edwards in thirty-two episodes of The Andy Griffith Show.

In 1968, Hope’s familiar character took on a whole new dimension when she portrayed Mrs. Gilmore, one of the Satan worshippers attempting to corrupt poor Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby. After her turn as one of the devil’s minion, try watching her in The Andy Griffith Show. You’ll never look at sweet old Clara in the same way.

Hope was still an active and in-demand actress at the time of her death in 1979 at age 83.

Comments

IMT: tree

The inspirational word this week on the Inspire Me Thursday website is “tree”.

After years in the jungle, Tarzan never imagined he’d spend his golden years in a tree.

Comments

IF: unbalanced

The Illustration Friday challenge word this week is “unbalanced”.

They don’t come much more unbalanced than Armin Meiwes. WARNING! His story is not for the faint of heart.

Armin Meiwes was an active member on the fetish fantasy website, The Cannibal Cafe. In December 2001, he posted a message seeking a dinner guest. After screening several candidates, he began more serious correspondence with fellow German Bernd Jürgen Brandes. Through a month of email conversation, Meiwes discovered, to his delight, that Brandes’ fantasy was to be killed and eaten. Meiwes was only too happy to oblige.

In March 2002, Brandes came to Meiwes’ home in Rotenburg. Meiwes gave Brandes large amounts of alcohol and painkillers. He then led Brandes to his bathtub to lie down. Once Brandes was properly anesthetized (but conscious), Meiwes cut off his guest’s male organ and fried it in a pan with onions and garlic. Meiwes served the cooked appendage to the two of them, as Brandes slowly bled to death. After they consumed as much as they could, Meiwes administered more alcohol and alcohol-based cold medication and left Brandes to die in the tub. Meiwes went into another room and read a Star Trek adventure book for three hours. Then, he returned to the tub, cut Brandes’ throat, and hung the body from a meat-hook. He began the task of butchering Brandes’ body for further consumption. He stripped, separated and bagged sixty-five pounds of Brandes’ flesh, which he stored in a chest freezer. He attempted to hide the bags under some frozen pizzas. Over the next ten months, Meiwes ate some of the flesh every day.

Meiwes was arrested in December 2002, after a college student contacted the police upon seeing advertisements for victims and details about the killing on the internet. Investigators searching Meiwes’ home found a videotape of the killing and approximately fifteen pounds of human flesh in the freezer.

On January 30, 2004, Meiwes was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to eight and a half years in prison. Meiwes had admitted what he has done, although he debated the charge of murder, insisting that Brandes was a willing participant and was well aware of his fate.

Not satisfied with the manslaughter charge and the lenient sentence, a Frankfurt court retried Meiwes in 2006. He was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

Comments

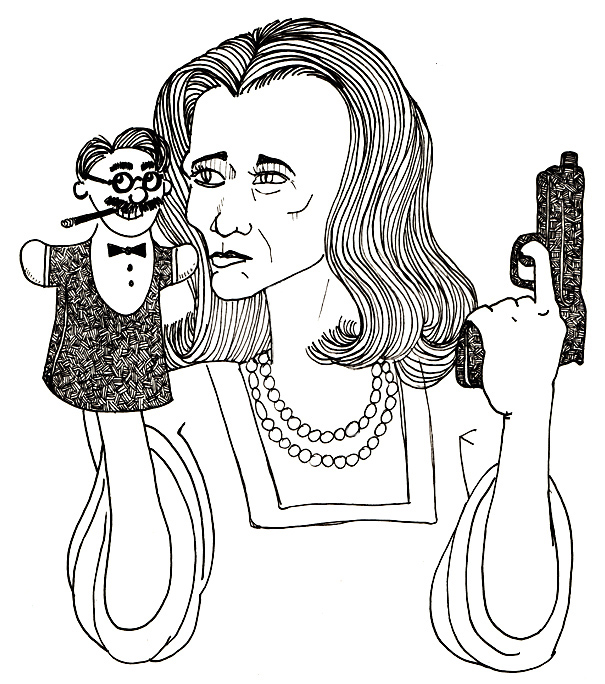

from my sketchbook: erin fleming

Thirty-year-old Erin Fleming was hired as secretary to eighty-year-old Groucho Marx in 1970. The two began a relationship. She persuaded Groucho to perform a one-man show that proved to be wildly popular. A performance at Carnegie Hall was recorded and released as An Evening with Groucho. That, too, was a huge success.

Groucho’s son, Arthur, accused Erin, a failed actress, of exploiting an increasingly senile Groucho in pursuit of her own stardom. In Groucho’s later years, his heirs filed several lawsuits against her. One allegation leveled against Fleming was that she was determined to sell Groucho’s favorite Cadillac against his wishes. When Groucho protested, Fleming allegedly threatened, “I will slap you from here to Pittsburgh.”

Groucho’s health began to decline quickly in 1977 and he was in and out of the hospital for most of the summer. On August 19, 1977, Erin Fleming made this statement to the Associated Press: Grouchos just having a nice little dream now. Hes just going to have a nap and rest his eyes for the next several centuries. Erin left the hospital, leaving Arthur, Arthur’s wife and son in Groucho’s room when he died. The court battles over Groucho’s estate dragged into the early 1980s, but judgments were eventually reached in favor of Arthur Marx, ordering Erin to repay $472,000.

Erin’s mental health deteriorated in the 1990s. She used to go into Saks Fifth Avenue, try on clothes and put them on lay away, and never go back to finish the sale. She would twirl around Saks and sing to herself. She was arrested in Los Angeles on a weapons charge, and spent much of the decade in and out of various psychiatric facilities. Reports from later in her life identified Erin as homeless. She committed suicide in 2003 by shooting herself.

Comments

from my sketchbook: tod browning

Charles Browning grew up in Louisville, Kentucky. He was a huge baseball fan and he was pals with his uncle, “Old” Pete Browning, a 3 time batting champ, who stole 103 bases in 1887. Charles’ Uncle Pete’s commissioning of a bat provided the start of the Hillerich & Bradsby bat company, famous for their Louisville Slugger model.

At 16, Charles changed his name to Tod and ran away from home to join the circus. He traveled with various sideshows and carnivals taking on many jobs. He worked as a talker (not a “barker”). He performed a live burial act billed as “The Living Corpse”, and performed as a clown with Ringling Brothers. He would draw on this experience as inspiration for some of his film work.

Later, while working in variety theater, he met director D.W. Griffith and began working as an actor. He appeared in over fifty films. In 1915, he was involved in a near-fatal car wreck. Tod was sidelined as he convalesced and he wrote scripts. He made his directorial debut in 1917. He directed twenty or so films (including one with Lon Chaney, Sr.) that were not particularly popular. In 1925, he reunited with Chaney for The Unholy Three, which was a huge success. He made ten more films with Chaney including The Unknown (co-starring a young Joan Crawford) and London After Midnight, both in 1927.

Based on his popularity, Tod was chosen to direct the 1931 horror classic Dracula. After Dracula, Tod began work on a film based on a short story by Clarence “Tod” Robbins, the screenwriter of The Unholy Three. The film was Freaks. It was the story of a love triangle between a wealthy circus dwarf, a gold-digging acrobat and a strongman. Tod cast actual sideshow “freaks” and the studio heads at MGM were apalled. The film contained many scenes that were disturbing for 1932. The studio demaded edits. It was released and banned throughout the world. Tod’s career was derailed. He directed four more films, including a remake of London After Midnight. He left the Hollywood scene in 1939 and became a recluse.

In 1950, after years of heavy smoking, he developed throat cancer and required tongue surgery. He moved in with some friends in their home in Malibu. He was found dead in their bathroom on October 6, 1962 at the age of 82. He had stayed out of the spotlight for 23 years.

Comments

DCS: willie best

Willie Best arrived in Hollywood by way of Sunflower, Mississippi as chauffeur for a vacationing couple. He began performing with traveling shows in California. He became a regular character actor in Hollywood after a talent scout discovered him on stage. Along with black actors like Lincoln Perry (better known as “Stepin Fetchit”), Willie was usually cast in supporting film roles of janitor, valet, elevator operator or train porter. Willie’s characterization of the stereotypical Hollywood lazy black man earned him the stage name “Sleep ‘n’ Eat.” He was billed under this name for many of his films, if he was billed at all. He appeared in over one hundred films in the 30s and 40s. Bob Hope, with whom he co-starred in 1940s The Ghost Breakers, called Willie “the best actor I know.” Hal Roach called him one of the greatest talents he had ever met.

In the 1950s, Willie played Charlie, the elevator operator on the popular sitcom My Little Margie and the valet of the title character on another sitcom, The Trouble with Father. Gale Storm, Willie’s Margie co-star, said he was an absolute joy to work with.

Willie’s lifestyle differed vastly from his on-screen character. He was a sharp dressed socialite who kept company with fine women, and eventually fine drugs. He was busted on narcotics charges in 1951.

By the late 50s, Willie and his screen persona were vilified by civil rights groups, forcing him to withdraw from show business. Once beloved as a great clown, then reviled, then pitied, Willie died in obscurity from cancer at age 45 at the Motion Picture Home Hospital in 1962.

His grave remained unmarked for almost fifty years until fans purchased a headstone in 2009.

This post got a mention on the very cool Celluloid Slammer website. Thanks. — JPiC

Comments

IMT: spain

The inspirational word this week on Inspire Me Thursday is “Spain”.

Once I was the King of Spain

(Now I eat humble pie)

Oh my unspeakable wife Queen Lisa

(Now I eat humble pie)

I’m telling you I was the King of Spain

(Now I eat humble pie)

Now I work at the Pizza Pizza

“King of Spain” by Moxy Fruvous

Here is Moxy Fruvous performing the song:

Comments

IF: blur

The weekly challenge word currently on the Illustration Friday website is “blur”.

Seven hours ago, Henry went to mail a letter. The rest is a blur.

Comments

from my sketchbook: my greatest job

As I watched the 2009 baseball postseason, I thought about my long association with the Philadelphia Phillies.

As a kid, I was never a sports fan. My brother and father would park themselves in front of the television and rabidly watch anything that remotely resembled a sporting event. Depending on the time of year, our house was filled with the sounds of kicked footballs, batted baseballs, whacked hockey pucks or basketballs swishing through nothing but net. There was always some sort of elimination round of some playoff of some series — punctuated by the heated and opinionated arguments between my brother and my father. I was usually off somewhere drawing. As far as I was concerned, one sport was just as boring as the next. But soon, all that would change.

In October 1977, I passed my driving test and was awarded a license to operate a motor vehicle in the state of Pennsylvania. I happily offered to run errands for my mom and drive friends around. I used any excuse I could think of in order to tool around Northeast Philadelphia in the most reliable of vehicles from the Pincus Family motor pool: my mom’s 1969 Ford Galaxie.

The Galaxie was a massive assemblage of steel and rubber that was sturdy enough for battle. It boasted a dashboard that looked like it belonged in commercial airplane. In what was obviously an exercise in poor planning, the radio was wedged into a most inconvenient corner space to the far left of the steering wheel. This gave only the driver control of the soundtrack for each ride.

The 1977 baseball season ended and the first place Phillies were once again denied a trip to the World Series, this time by cross-country rivals, The Los Angeles Dodgers. It was in that time between the 1977 Fall Classic and ’78 Spring Training that my brother gave me a valuable piece of advice, and probably the only piece of advice from my brother I ever followed. He suggested that I apply for a job at Veterans Stadium, home of the Philadelphia Phillies, as a vendor. It proved to be the greatest job I ever had.

In February 1978, baseball players began reporting to training camps throughout Florida. Meanwhile in Philadelphia, I obtained the necessary employment certificates allowing me to work, in compliance with Pennsylvania law. I borrowed the Galaxie and carefully navigated southbound Interstate 95, a thoroughfare I had only traveled once before, and that was while accompanied by a driving instructor. With my hands properly on the steering wheel at 10 and 2, I kept the car steady and as far to the right on the highway as legally possible. After a grueling forty-five minute ride (that should have taken twenty), I arrived at the 50 million dollar multi-purpose concrete structure that was known to locals as “The Vet.” I parked my car in the enormous lot and followed the signs towards the employment office. An uninterested woman with no inflection in her voice asked me some questions covering my age, where I attended school and how I heard about the job. She then directed me to another office that was empty except for an industrial-looking camera and a neutral photo backdrop suspended from a metal frame. I stood before the frame and smiled when cued. After several minutes, I received my laminated ID card and just like that I was officially a vendor for Nilon Brothers, the company that operated the food service at the stadium. I didn’t actually work for the Phillies, so, unfortunately, I was not on the same payroll as Mike Schmidt. But, in sixty days, I’d eagerly return to hawk my wares amid the cheering crowd of baseball faithful.

My brother and a number of his friends had worked as vendors for five years prior. I was welcomed to the fold as long as I could provide transportation to the ballpark as part of a carpool. I committed and was welcomed once again, this time more sincerely. Arrangements were made and I was to drive a car full of my brother’s buddies to The Vet every fifth home game or when needed.

It was unseasonably cold the first week of April in Philadelphia, but that didn’t keep the 1978 baseball season from starting. I got a call from one of my fellow vendors informing me when to be ready for pickup for Opening Night. A car packed with my brother’s friends pulled up in front of my house. A horn honked as my signal to join them in seconds or be left behind. I scurried down the front lawn, and climbed into the back seat, squeezing between two hulking college seniors. They were anxious to start the new vending season, as they had all turned 21 and were now legally permitted to sell beer. That’s where the real money was.

The policy of vending for Nilon Brothers was this: Vendors essentially worked for themselves, meaning there was no salary. A vendor would arrive at the stadium several hours before a game and queue up for admittance. Once the vendor entrance opened, one would proceed to what we called “the laundry.” It was a counter where a man sat and distributed smocks in exchange for your ID badge and ten bucks. The smock was a red, white and blue-striped pajama top that identified you as an authorized Nilon employee. I suppose Nilon felt that carrying a tray of foodstuff and screaming one’s head off was not enough to allow for proper recognition. At the end of the night, once your smock was returned (no matter how soiled or sweat soaked), you would receive your ID and full deposit. After putting on the clown-like smock and tying on your own supplied change apron, vendors would head to one of four vendor-only commissaries placed strategically throughout the stadium. I, and my carpool colleagues, worked out of commissary 535 in the right field upper deck. The commissary was set up like a cafeteria. There were sections for each product – soda, peanuts, beer – from which a vendor choose his item for the night. I sold Cokes, which were dispensed in waxed cups and arranged in wire trays of twenty. A tray of Cokes was purchased by the vendor – that’s right, purchased – for $14.25. Different products cost different amounts and, therefore, offered different profit margins. With a catchy “call” and swift feet, a tray of twenty Cokes at eighty cents apiece brought the vendor $16.00 – and a profit of a buck seventy-five. An average summer game would net about thirty-five dollars, a huge sum to a seventeen-year old. On a really good day, fifty bucks could easily be made, if a fair amount of hustling was involved. Rain delayed games were great because there was a captive audience, no game and nothing to do but buy food. Vendors loved rain delays. Oh yeah, vendors had to provide their own change. Aside from a workplace, Nilon Brothers provided shit.

My first night of vending was exciting and I was ready to vend. However, after toting a heavy metal tray laden with twenty, ice and soda-filled cups up and down steep, cement steps into the dizzying heights of the 700 level, I was dragging my ass. The tray weighed a ton and, due to the chill in the air, Cokes werent exactly a hot commodity. As baseball season went on and the weather got warmer, vending blossomed into a great experience. I hustled through the crowds, deftly tendering two dimes for every dollar I received for a Coke. I perfected my attention-getting call of “Heeeeeeyyyy! Coooooooo-ke He-YAH!” as I worked the bleacher throngs. The camaraderie among most vendors was great. I acknowledged the other vendors I passed with a wink, as though we were part of a secret club. There was McKenna, a geeky string bean with thick glasses and his unmistakable call of “Give your tongue a sleigh ride!” when he sold ice cream. There was old Charlie Frank, a legend among the elite clutch of hot dog vendors, with his rapid-fire call of “DoggieDoggieDoggieDoggieDoggieDoggie.” There was my brother’s pal Scott, another hot dog vendor, who served up two dogs on one bun, affectionately called a “Scott-dog.” Since hot dog sales were tallied by the roll inventory, this treat was not uncommon, but only available to vendors.

Nilon Brothers didn’t care much for competition. Enterprising, yet unauthorized, street vendors that set up on bordering Pattison Avenue infringed on Nilon’s high-priced fare. Besides that, they were vending illegally on private property. Each night, policeman would systematically confiscate shopping carts filled with Philly soft pretzels from some rogue salesman. The offender would be chased from the premises and his offerings carted into the bowels of some stadium storage area. Those storage areas were adjacent to the vendor laundry. One night at the seventh-inning vendor departure time, as a group of us were returning our smocks, a voice from behind inquired, “Are these pretzels for anyone?” We turned around to see Jim Lonborg, the lanky Phillies pitcher, who had just gotten pulled from the evening’s game. Upon receiving several shrugs from the cluster of vendors, Lonborg grabbed a strip of eight baked-together pretzels, jammed them into the webbing of his glove and headed off to hit the showers.

The drives home from the game were an adventure as well. If I was a passenger, I was usually relegated to the back seat where I had to survive the smell of at least five of my brother’s friends, all sweaty and tired, but charged with adrenaline. If I was the evening’s driver, I had to maneuver around the ancient train tracks that littered Delaware Avenue, while deflecting the passenger trying to reach through my steering wheel in an attempt to change the radio station. When I’d get home my parents would ask who won. “Who won?,” I’d reply, “I don’t even know who was playing. I was too busy making money.”

On October 1, 1978, along with the Phillies season, my career as a vendor came to an end. The weather had turned cold and I needed to secure a job that lasted more than a few months.

In 1996, I began my tenure as a Phillies season ticket holder. With the package we purchased, my family began attending every Sunday home game the Phillies played. Today, as my wife and I sit in the stands of Citizens Bank Park, the new home of the Phillies, there are several vendors ambling through the crowd that I recognize thirty-one years later. Their calls are raspier and their gaits lethargic, but they are unmistakably the same guys. It seems sad to me that men of advanced age are still working the ballpark mobs. I suppose they don’t want to give up the greatest job they ever had.