In 1941, Merriman Smith became the White House correspondent for United Press International (UPI), a position he held until the Nixon administration. He began the tradition of closing his presidential conferences with “Thank you, Mr. President,” a practice still used by current correspondents.

On November 22, 1963, Merriman Smith sat with several other reporters in the back of a radio car as it made its way down Elm Street in Dallas, Texas a few hundred feet behind the presidential limousine. Merriman, a regular at a shooting range frequented by Secret Service agents, immediately recognized the sound of three distinct gunshots. He looked up to see a commotion in the open-top presidential vehicle as it sped away. Merriman immediately grabbed the radio and fired off a bulletin to the UPI news desk a bulletin that, at this point, was pure speculation. A bulletin that could bring him notoriety as easily as it could ruin his career. A mere four minutes after shots rang out in Dealey Plaza, Merriman dictated “THREE SHOTS WERE FIRED AT PRESIDENT KENNEDY’S MOTORCADE IN DOWNTOWN DALLAS” to the operator at UPI headquarters. He waited for confirmation as the Associated Press’ Jack Bell tried to pull the phone away. Merriman’s words were the first account the world received of JFK’s assassination. The press car followed the limo to Parkland Hospital. As it pulled into the emergency room entrance, Merriman tossed the now-dead phone to Bell and ran up to a Secret Service agent who answered his query about the President’s condition with “He’s dead, Smitty.”

Thinking quickly like a true newsman, Merriman hitched a ride with a Dallas policeman to the airport in time to see Vice-President Lyndon Johnson sworn in as the 36th President of the United States.

In 1964, Merriman won the Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the assassination of President Kennedy. He was the first to use the term “grassy knoll,” a term that would appear in virtually every future account of the incident.

In 1970, Merriman recognized one more sound of gunshot. It was the one that came from his own revolver. The one he used to put a bullet in his head.

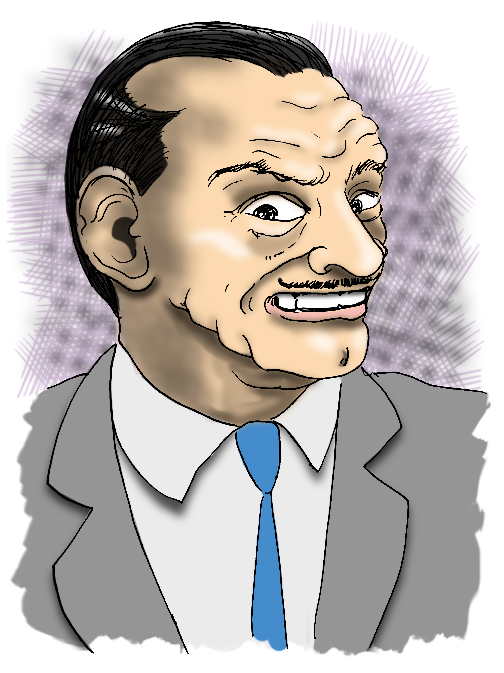

Wow! He certainly has a dramatic life story with a tragic ending. I like the expression you captured on his face.

What a tragic end to a life that shared such a significant event with so many of us.