Passover — the holiest day on the Jewish calendar after Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Shavuot, Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah …..um, where was I ?

Oh, yeah. Passover. Passover recounts the story of the ancient Israelites’ long journey out of slavery and oppression by Egypt and the Pharaoh. The Jews were enslaved and ordered to build the pyramids. This, of course, was the last time any Jew attempted a large home construction project with his own hands. The poor children of Israel were miserable and looked to their leader Moses for comfort and a remedy to their problems.

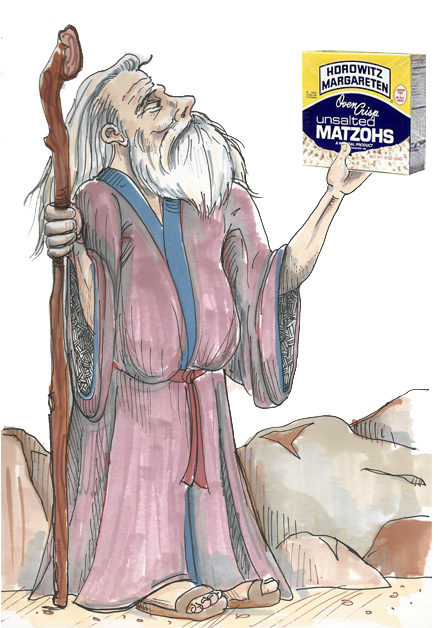

Moses demanded that the uninterested Pharaoh “let his people go.” With some assistance from God, Moses warned of ten plagues that would be brought upon Egypt until the Jews were freed. After an unrelenting wave of locusts and boils and flaming hail and anthrax (the disease, not the band — although that would have definitely qualified as a plague), Pharaoh said “Alright already! Beat it!” and granted the people their freedom. Wasting no time, the Israelites rapidly gathered their belongings and split. In their haste, they quickly grabbed the dough that had been baking on the hot rocks, not allowing it to properly rise. Because of this very act, this simple exercise in impatience, every year on Passover, Jews are condemned commanded to eat matzo in celebration of their freedom.

My observance of Passover has changed throughout the various stages of my life. As a child, there was little to no observance of Passover in my house. Of course, we had the obligatory single box of matzo and the occasional can of chocolate macaroons, but they held an equal place at the table alongside the plastic-wrapped loaves of bread. My father wasn’t going to stand for this “matzo shit” when he craved a bologna sandwich. Thirty years ago, when I met my wife and her traditionally observant family, I was introduced their elaborate seder. My in-law’s seder, the steadfast Passover meal, was a relative-stuffed, marathon event in which my father-in-law, reading from a generations-old tome, chronicled the tale of the Exodus in what seemed like real time. The entire ritual was meticulously orchestrated — from the reciting of the ma nishtana, to the off-key, communal singing of prayers — until we reached page 62 in the Haggadah and dinner was served. As the years rolled on and the massive preparation began to take its toll on my beleaguered in-laws, the seder has evolved into a much more intimate affair. The guest list has been whittled down to the families of their three grown children. Since my in-law’s grandchildren range in age from preschool to thirty years old, participation seems to excite only the smaller ones. Seated at the table, the older grandchildren can be caught observing their younger counterparts with glazed expressions, betraying conflicting feelings of fond memories and detachment. Others at the table are frantically calculating the arrival of page 62. My father-in-law’s one-time epic dissertations on the adventures of Moses and his freedom-seeking crew has been reduced to, what we fondly refer to as, the “Reader’s Digest” seder.

Matzo is the most familiar symbol of Passover. Both Jews, who suffer rejoice in its annual arrival, and non-Jews, who have sampled it in curiosity, are accustomed to its presence on supermarket shelves. Even among the assembly of unfamiliar products, like gefilte fish, farfel and kichel, matzo has become the Passover equivalent of chocolate bunnies… sort of. Not renowned for its versatility, inventive chefs (such as my mother-in-law) have sprung unlikely offerings like matzo lasagna (using strips of matzo in place of noodles) and matzo pizza (using matzo instead of anything that remotely resembles pizza) on their invited Passover visitors. These preparations have their hearts in the right place , but their taste buds have taken the eight day celebration off. An age-old dish, created to tolerate the eating of matzo and to mask its bland taste and cardboard-like texture, is matzo brie or fried matzo. Matzo brie, depending on whose family tradition you are following, can be likened to anything from French toast to an omelet to a doorstop. Years ago, my wife and I had a heated debate over the proper way to prepare matzo brie. Of course, we were each used to the way it was concocted by our respective mothers. I came to really love the way my wife made matzo brie , despite its noticeable difference from how my mom made it. The reason, I figured, was: number one — I can’t cook to save my life and number two — I damn well better prefer my wife’s cooking over my mother’s. Oh, my wife’s matzo brie is really good, too.

While our methods of honoring the redemption of the children of Israel were virtually non-existent, my mother did like making matzo brie and my brother and I loved eating it. We would sit at the kitchen table and carefully watch as my mother eyeballed the perfect amount of oil into her heated electric skillet. Then, in one fluid motion, she’d remove every insipid slice of plain matzo from a box and run the stack under a rushing stream of water from the kitchen faucet, deeply soaking every piece. The next step would be breaking the saturated mass into bite-sized pieces and combining the result together in a bowl of an egg, milk, salt and pepper mixture — coating each shard in preparation for frying. Once she was satisfied with the coverage, she’d dump the whole shebang into the crackling oil and shuffle it around for several minutes until it was golden brown and some pieces fused together. My brother and I hungrily gaped at the pan as my mother dished out equal portions and warned us to eat slowly, lest we get indigestion (this was a yearly practice associated with the consuming of my mother’s matzo brie). My brother and I would take turns with the cinnamon sugar and maple syrup, adjusting the fare to our individual liking.

One day during a particular Passover in my youth, my mother was not around when my brother got a hankering for matzo brie. He decided after years of careful observation and making mental notes, he could flawlessly duplicate my mother’s recipe with a result that would pass a blind taste-test with no problem. I stood back as my brother assaulted the kitchen. He spun the dial on the skillet to the setting he had seen mother select countless time before. He gathered the eggs, the milk, the salt, the pepper and the familiar mixing bowl and set them on the counter like little food-staple soldiers. Then, he turned to the table to choose the main ingredient — the missing element that puts the “matzo” in “matzo brie.” Unfortunately, this was my dear brother’s downfall. He mistakenly appropriated a box of egg matzo instead of its stiff, innocuous comrade. Egg matzo, as its label so cautiously warns, is for exclusive consumption by children and the infirm. Its inclusion of fruit juice instead of water makes for a softer, almost palatable, alternative to the regular “bread of affliction” that is the preferred celebratory punishment choice. When commingled with the wet ingredients and the baptismal-like drenching of water, egg matzo becomes a disastrous mess once it hits a pan of hot cooking oil. My brother found this out the hard way. My mother came home and witnessed the after-effects of what came to be known around my house as “The Fried Matzo Incident.” One new electric skillet later, my brother never attempted fried matzo again.

So, the tradition of Passover in my life has gone from unfamiliarity to extremely traditional to my current feeling of skeptical indifference. Only two things have remained constant — confirmation of the start time for the annual network telecast of The Ten Commandments and, of course, matzo.

The bread of our affliction indeed. I can hardly wait to suffer through, errr, I mean enjoy the annual eating o’ the matzo. Happy Passover to you!

Well I do not know where to begin. I have just stood in my kitchen for five days straight trying to invent some really tasty dishes and especially stuff for those unhappy vegetarians. I have washed, scrubbed, peeled, fried and roasted for days and still have two days to go. So-o-o-o tell me again who is suffering? Also, I want to see a smile on everyone’s faces when the little ones sing their songs and ask the Four Questions. Now that I have said my piece I will go back to making that delicious Passover chocolate mousse that everyone loves. Love always MIL

Well, first off, your Mom raised no fool! 🙂 Secondly, I love the combination of illustration with the pop art box of matzos! Thank you for the history and your amazing humor! Blessings to you on Passover.

The contents of Comment #2 do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the management.

Chag Samaech!

Love this whole post. So informative about traditions. If Moses had known about this matzoh tradition lasting for millenia, do you think he would’ve told people to take their time packing?

I love it! Too bad about the mousse.

Thanks for the picture but why so big nose?