What do you do on your day off? If you’re like most people, you are most likely mowing your lawn, catching up on your housework or even sleeping late. If you’re Phineas and Ferb, then you’re probably building the world’s coolest rollercoaster or giving a monkey a shower. However, if you are me (and I’m betting that you aren’t) then you are likely to spend your day off seeking out and wandering amidst the final resting places of the famous, the not-so-famous and the forgotten. Because I only had one day remaining from my available vacation allotment, I needed to limit my grave visits to a local level.

I started by driving out to Philadelphia’s famed “Main Line”, an historically affluent area of the city, with my destination being Westminster Cemetery. (Westminster backs up to West Laurel Hill Cemetery, which I visited last December.) Among the huge mausoleums and marble headstones lies the Hires family plot and its patriarch, Charles Hires.

Hires worked in a Philadelphia pharmacy as a teenager. As a young man, he was introduced to “root tea” at the New Jersey hotel where he spent his honeymoon. After experimenting with some of the ingredients, he soon marketed “Hires’ Root Beer”. At the 1876 U.S. Centennial Exposition, Hires, a proponent of the Temperance Movement, offered his beverage as an alternative to alcohol and the public responded favorably. He became a millionaire.

Not far from Westminster is the tiny Gladwyne Methodist Church Cemetery, a small plot of land behind a nondescript church in the Philadelphia suburb of Gladwyne. Just behind the church’s back steps is the grave of beloved Philadelphia Phillies’ player and later broadcaster Richie Ashburn.

Ashburn was part of the celebrated “Whiz Kids” in 1950. He spent twelve of his fifteen Major League seasons with the Phillies and later spent thirty years in the Phillies broadcast booth alongside his friend Harry Kalas. “Whitey,” as he was known by friends and fans, was inducted into Baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1995 in a ceremony that included Phils’ third baseman Mike Schmidt. Ashburn passed away in 1997 in a New York hotel room, just hours after broadcasting a Phillies-Mets game.

A little closer to my home, straddling the border between Philadelphia and Montgomery County, is Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. This sizable, multi-sectioned but well-marked Catholic cemetery, filled with ornate headstones and religious statuary, is under the auspices of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. There are many examples of the “weeping angel“, a reoccurring figure among grave markers (like this one, adorning the freestanding crypt of one Edward F. Britt…)

As expected, Jesus is also well represented among the sculptures. His likeness is featured on many headstones and there are several life-size figures, like these, throughout the grounds. (The large stone Saviour at the Witkowski plot seemed to be acting as maître d’. The one on the Baumann grave, high atop a four-foot tall pedestal, looked as though he was directing traffic.)

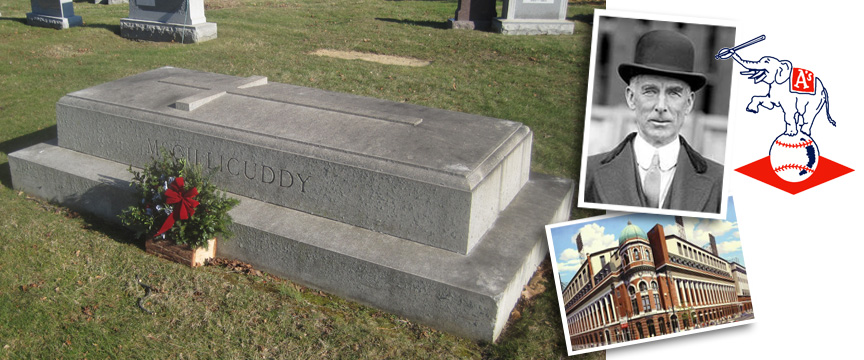

Slipping inconspicuously past the cemetery office, I made my way to the curbside grave of Cornelius McGillicuddy, better known as Connie Mack. His monument bears no other inscription besides “McGillicuddy”.

Mack was the owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics for fifty seasons, an unsurpassed tenure for a manager in North America sports history. Under his leadership, the A’s appeared in eight World Series, winning five of them. After financial difficulty due to the team’s poor performance in later years and the popularity of the crosstown rival Phillies, 88-year-old Mack retired in 1950, saying “I’m not quitting because I’m getting old, I’m quitting because I think people want me to.” In 1953, Shibe Park, the A’s home field at 21st Street and Lehigh Avenue, was renamed Connie Mack Stadium. In 1954, he sold the team to a Midwest businessman who promptly moved the A’s to Kansas City. Mack died two years later.

Closely following my highlighted map, I maneuvered up a paved, but narrow, road to Section I. This sloping plot, rimmed with large private mausoleums and enormous cement crosses, is the eternal home of restaurant entrepreneur Joseph Horn and other (deceased) members of the Horn family.

In 1888, Horn and his partner Frank Hardart opened a tiny luncheonette on South 13th Street in Philadelphia. Their French-drip coffee, a Southern favorite, was unique to the area and word of mouth brought in non-stop business. Soon, the pair opened the first Automat in the United States. It was based on a similar concept popularized in Germany. The Automat featured prepared foods behind small glass windows and coin-operated slots. Cashiers, known as “nickel throwers”, dispensed coins for customers. A full, but simple, meal could be purchased for under a dollar. Using the slogan “Less Work for Mother,” the company also pioneered easily-served “take-out” food. Horn & Hardart’s Automats remained popular for nearly a century. At one point, they operated over 150 restaurants in Philadelphia and New York, until the rise of fast-food chains brought a gradual end to their empire. The company closed its last Automat in 1991. (Frank Hardart is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon, Pennsylvania.)

Just up a hill from the Horn plot is the grave of Matt Kilroy, one of the greatest baseball pitchers you never heard of.

In 1886, Kilroy, a 20 year-old rookie, pitched 66 complete games and struck out a still-unmatched 513 batters. (The rules were different at that time and the pitcher’s mound was fifteen feet closer to the plate then.) He finished the season by pitching a 6-0 no-hitter for his Baltimore Orioles. In his sophomore season, he pitched and won both games of a double-header. And he did that twice.

Deeper into the cemetery is another family plot – this one of prominent Philadelphia family, The Kellys. Jack Senior and Junior are both buried here.

Jack B. Kelly, Sr. was the first three-time Olympic Gold medal winner in the sport of rowing. He won 126 straight races in the single scull. His son, Jack Jr., was also an Olympic medalist in rowing, taking home the Bronze in 1956. In 1975, Jack Kelly Jr. made an unsuccessful bid for mayor of Philadelphia. At the time, he was involved in a secretive affair with the locally famous Rachel Harlow. Harlow, the former Richard Finocchio, was a transsexual. His opponents threatened to campaign with the slogan “Do you want Rachel Harlow as First Lady of Philadelphia?”. Kelly dropped out of the race. In 1985, just after being named as president of the United States Olympic Committee, he suffered a heart attack while jogging on East River Drive (subsequently renamed “Kelly Drive” in his honor). Of course, Jack Jr.’s sister was actress Grace Kelly.

Close by the Kellys is the grave of another famous Philadelphian, Mayor Frank Rizzo.

A policeman in the 1940s, Rizzo rose to become Police Commissioner in 1967 and, then eventually, a two-term mayor of the city. His often controversial policies and actions made him equally revered and reviled by the people of Philadelphia. The city charter rule prohibiting more than two consecutive mayoral terms forced Rizzo to step down. But in 1991, he switched political parties and, again, mounted a campaign for mayor. Just after a victory in the primaries, Rizzo died of a massive heart attack in his office while waiting for his lunch.

As I was leaving Holy Sepulchre, I passed this marker and did a double-take.

As they say – you can’t judge a book by its headstone.

A few blocks southeast of Holy Sepulchre is Ivy Hill Cemetery. This neighborhood burial ground is small, cluttered and poorly marked, with not a single directional sign anywhere. It is also the new permanent address of boxing legend “Smokin'” Joe Frazier, who passed away just last month. But, I found two far more interesting residents on the grounds. Just inside the massive stone archway entrance, a few feet from the cemetery office, is the grave of an unknown child commonly referred to as “The Boy in the Box“.

In February 1957, the battered, naked body of a small boy was discovered wrapped in a torn blanket in a cardboard box in a rural area in the Fox Chase section of Northeast Philadelphia. An intense investigation led nowhere and still, over 50 years later, the case remains unsolved. The story has been the basis of many reports and has been fictionalized on several TV shows dealing with forensic crime investigations. In 1998, he was reburied at Ivy Hill with a new black marble headstone. The original grave marker was placed at the foot of the new grave.

Just behind the Unknown Child, I spotted a striking statue high on a stone pedestal. So, I snapped a picture.

It’s the grave of Private Melville Freas who served in Company A, 150th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the Civil War. At the Battle of Gettysburg, Freas and four other soldiers were taken prisoner and moved to a Confederate prison camp in Virginia. His colleagues all died in custody, but Freas was released nearly a year later. After the war, Freas returned to Philadelphia. In 1914, at age 73, he purchased a gravesite at Ivy Hill and commissioned a statute of himself to be placed there. The base was engraved with the names of his four fellow prisoners as well as his own. Freas died in 1920 and was buried beneath the statue as per his wishes.

I left Ivy Hill and headed to Chelten Hills Cemetery just down Michener Avenue. Chelten Hills is a hilly, unkempt, poorly laid-out cemetery. And, honestly, I have no distinct memories of my brief visit.

And it looks like the feeling is mutual.

* * * * *

I am glad that you enjoyed your day off Josh. Thanks for coming to my rescue at my office where the retail chaos of the Holiday season required a strong back up such as yourself!

Very great post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to say that I have really enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I will be subscribing on your feed and I am hoping you write once more very soon!