On a Sunday morning, as winter became spring, I decided there was no better time to explore a cemetery. I chose Har Nebo Cemetery, a small, but jam-packed final resting place for over 36 thousand interments… and it’s not far from my house. Har Nebo was established in 1890 and is named in honor of the mountain in Jordan on which Moses viewed The Promised Land just prior to his death. From my vantage point at an intersection in bustling Northeast Philadelphia, I could see a Shop Rite supermarket and a Halal slaughterhouse, but no Promised Land. And I looked hard.

On a Sunday morning, as winter became spring, I decided there was no better time to explore a cemetery. I chose Har Nebo Cemetery, a small, but jam-packed final resting place for over 36 thousand interments… and it’s not far from my house. Har Nebo was established in 1890 and is named in honor of the mountain in Jordan on which Moses viewed The Promised Land just prior to his death. From my vantage point at an intersection in bustling Northeast Philadelphia, I could see a Shop Rite supermarket and a Halal slaughterhouse, but no Promised Land. And I looked hard.

In the early days of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, family members of loved ones buried at Har Nebo were distressed when, on an attempt to visit a grave, found the gates padlocked shut and spied, through the surrounding barbed-wire topped chain-link fence, the grass and vegetation overgrown, unkept and out of control. Calls to the facility office went unanswered. A local Jewish newspaper ran an article exposing the current state of the grounds, prompting the owners to assure everyone that they planned to clean the place up, once the world had a better handle on COVID and its transmission was better understood. Sort of true to their word, a group of volunteers were recruited and, over the course of a couple of weekends, Har Nebo was brought back to life…so to speak. I was a bit leery prior to my visit this morning, but I found Har Nebo to be well-maintained and surprisingly well-marked with clearly placed identification and directional signs displayed at each section. I drove my car through the wide open entrance gate and headed down imaginatively named Office Drive to Section F, just a short distance from the main office.

In the early days of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, family members of loved ones buried at Har Nebo were distressed when, on an attempt to visit a grave, found the gates padlocked shut and spied, through the surrounding barbed-wire topped chain-link fence, the grass and vegetation overgrown, unkept and out of control. Calls to the facility office went unanswered. A local Jewish newspaper ran an article exposing the current state of the grounds, prompting the owners to assure everyone that they planned to clean the place up, once the world had a better handle on COVID and its transmission was better understood. Sort of true to their word, a group of volunteers were recruited and, over the course of a couple of weekends, Har Nebo was brought back to life…so to speak. I was a bit leery prior to my visit this morning, but I found Har Nebo to be well-maintained and surprisingly well-marked with clearly placed identification and directional signs displayed at each section. I drove my car through the wide open entrance gate and headed down imaginatively named Office Drive to Section F, just a short distance from the main office.

At the near corner of Section F, nearly hidden by a bush, is a plot marker inscribed “Gottlieb” and the individual grave marker of Eddie Gottlieb.

Ukrainian-born Eddie was, by his own admission, a born promoter. As a teenager in his new home of Philadelphia, Eddie played for, coached and owned several neighborhood basketball teams. With the sponsorship of a Jewish social club in South Philadelphia, Eddie presided over the oddly-named Philadelphia SPHAs (an acronym for sponsors South Philadelphia Hebrew Association). With no home court, the team was nicknamed “The Wandering Jews.” With keen entrepreneurial skills, Eddie scheduled games with other area teams and, in 1925, began the American Basketball Association, the country’s first basketball league. In the 40s, Eddie merged his league with a Midwest league to form the National Basketball Association. He coached, and later owned, the Philadelphia Warriors. Eddie was also the chairman of the league’s rules committee for 25 years, claiming responsibility for more rule changes in pro basketball than any other man. In 1959, Eddie recruited a young man named Wilt Chamberlain to play for the Warriors. In 1962, he moved his team to San Francisco, where they play today as the Golden State Warriors. The NBA “Rookie of the Year” Award was called the Eddie Gottlieb Trophy until 2022, when it was renamed in honor of Wilt Chamberlain. Contemporary Harry Litwack said of Eddie: “Gottlieb was about as important to the game of basketball as the basketball.” Eddie died in 1979 at the age of 81. For years, Eddie single-handedly created the NBA season schedules, reluctantly relinquishing the task to computer software just before his death.

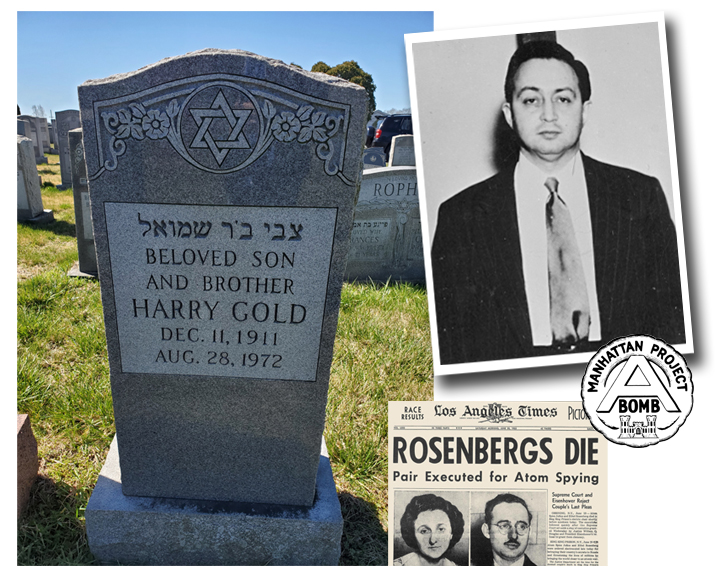

Towards the back part of Har Nebo, is Section O. Along a narrow walking path. flanked on both sides by tightly-positioned headstones, is the grave of Harry Gold.

Heinrich Golodnitsky emigrated to the United States with his family, leaving Bern, Switzerland in 1914. Passing through Ellis Island, the family was renamed “Gold” and young Heinrich was dubbed “Harry.” As a teenager, he worked at the Pennsylvania Sugar Company (later becoming the Jack Frost Sugar Company, now the current site of Rivers Casino). Harry saved his salary to attend the University of Pennsylvania, taking chemistry classes until his money ran out.

Under his parents’ influence, Harry became interested in Socialist ideals. A former classmate tried to recruit Harry into the Communist Party and, after initial hesitation, Harry reluctantly joined. He began covertly giving company secrets to his friend who worked at a rival manufacturing company. Around the same time, Harry took additional chemistry classes at Drexel University and befriended Jacob Golos, a notorious Soviet operative, who recruited Harry for espionage. Beginning in 1940, Harry was involved in the transmission of government secrets to the Soviet Union, including collaboration with Klaus Fuchs. Harry and Fuchs gave information about the Manhattan Project, the secret US research operation for developing the atomic bomb, to the Soviets. Fuchs was arrested and offered information about other spies working for the Soviets, including Harry Gold. Harry was arrested in 1950 and confessed to receiving classified information from David Greenglass, a machinist on the Manhattan Project. Greenglass’s testimony led to the arrest of his sister Ethel and her husband Julius Rosenberg. Harry was sentenced to 30 years in prison for his espionage activity. After many appeals, he was released from prison, serving approximately half of his sentence. He found work as a chemist at a Philadelphia hospital and died in 1972 at the age of 61. The combination of Greenglass’s and Harry’s testimony led to the execution of the Rosenbergs. Some, though, have doubted the truth of Harry’s claims.

A short walk from Harry Gold’s grave is the final resting spot of Stan Hochman.

Stan Hochman is a familiar name to Philadelphia sports fans. For fifty-five years, he covered the activities of the Philadelphia Phillies for the Philadelphia Daily News. A sometimes beloved — sometimes reviled — figure, Stan’s accounts of the team were always a source of discussion among fans of the Fightin’ Phils. He covered the city’s other sports teams, as well. According to his grave marker, he was the grand imperial poobah, too. Stan died at his suburban Philadelphia home at the age of 86… six years after the Phillies won their second World Series. He covered the first one, too.

I passed a few families milling through the gravestones, searching for the plots of loved ones or, perhaps, doing the same thing I was doing. I wasn’t going to ask. I made my way around to Office Drive and the open gates… leading me back into the world of the living.

I passed a few families milling through the gravestones, searching for the plots of loved ones or, perhaps, doing the same thing I was doing. I wasn’t going to ask. I made my way around to Office Drive and the open gates… leading me back into the world of the living.

And that Shop Rite.

* * * * *