A trip to a cemetery to seek out the graves of famous people (as I have been doing for nearly two decades) takes a lot of planning. Well, at least it used to. When I first started this little hobby, I would gather maps and plot routes and sometimes come away disappointed. Sometimes — more times than I would have liked — I was not able to locate all of the particular graves I was looking for. Cemeteries are not the easiest places to navigate and often I felt as though I was looking for the proverbial “needle in a haystack.” However, over the past twenty years, GPS technology available to the average grave-seeking Joe (or Josh, in this case) has become easier to use. So, today, I dispensed with printed maps for my trips to three local Philadelphia area cemeteries and went purely with the guidance of the (somewhat reliable) GPS app on my cellphone. Welcome to the 21st century, Josh.

A trip to a cemetery to seek out the graves of famous people (as I have been doing for nearly two decades) takes a lot of planning. Well, at least it used to. When I first started this little hobby, I would gather maps and plot routes and sometimes come away disappointed. Sometimes — more times than I would have liked — I was not able to locate all of the particular graves I was looking for. Cemeteries are not the easiest places to navigate and often I felt as though I was looking for the proverbial “needle in a haystack.” However, over the past twenty years, GPS technology available to the average grave-seeking Joe (or Josh, in this case) has become easier to use. So, today, I dispensed with printed maps for my trips to three local Philadelphia area cemeteries and went purely with the guidance of the (somewhat reliable) GPS app on my cellphone. Welcome to the 21st century, Josh.

Just north of Philadelphia is a quiet, pastoral cemetery appropriately named Sunset Memorial Park. Boasting a park-like atmosphere with beautifully manicured lawns, spectacular landscaping, mausoleums and even a separate pet cemetery, Sunset Memorial Park is the eternal home to over 15,000 “residents.” On a sunny hill, several rows back from the curb, is the grave of Sunset’s arguably most famous permanent occupant.

Just north of Philadelphia is a quiet, pastoral cemetery appropriately named Sunset Memorial Park. Boasting a park-like atmosphere with beautifully manicured lawns, spectacular landscaping, mausoleums and even a separate pet cemetery, Sunset Memorial Park is the eternal home to over 15,000 “residents.” On a sunny hill, several rows back from the curb, is the grave of Sunset’s arguably most famous permanent occupant.

Buried beneath this fairly simple marker is Gia Carangi.

Born in Philadelphia, Gia Carangi is acknowledged as the first “supermodel.” After being featured in ads in local newspapers, 17-year old Gia was signed by Wilhelmina Models, a prestigious agency in New York City. Gia soon appeared on the cover of Vogue magazine. (She’d be featured on the cover four more times.) She represented such iconic fashion brands as Armani, André Laug, Christian Dior, Versace, and Yves Saint Laurent. However, her meteoric rise to fame had its dark side. She was a regular at notorious disco Studio 54 and became entrenched in 80s drug culture. On several occasions, she threw tantrums during photo shoots and walked out to buy drugs. She was addicted to heroin by 1980 and many of her photographs were airbrushed to cover up needle marks. By the mid-80s, her career was in freefall. Many photographers refused to work with her and almost all of the top fashion houses dropped her from their rosters. By the end of 1985, she had turned to prostitution for drug money. She also contacted AIDS and her health took a swift decline. She passed away in 1986 at just 26. No one from the fashion world attended her funeral.

A little closer to my house is Montefiore Cemetery. I have been to Montefiore several times for funerals and have come across familiar graves by pure chance. I attended a funeral last year that was just a few feet from the graves of my aunt and uncle. On this day while search for the two famous grave on my list, I stumbled upon the graves of neighborhood acquaintances — a married couple whose plots were, curiously, not next to each other.

A little closer to my house is Montefiore Cemetery. I have been to Montefiore several times for funerals and have come across familiar graves by pure chance. I attended a funeral last year that was just a few feet from the graves of my aunt and uncle. On this day while search for the two famous grave on my list, I stumbled upon the graves of neighborhood acquaintances — a married couple whose plots were, curiously, not next to each other.

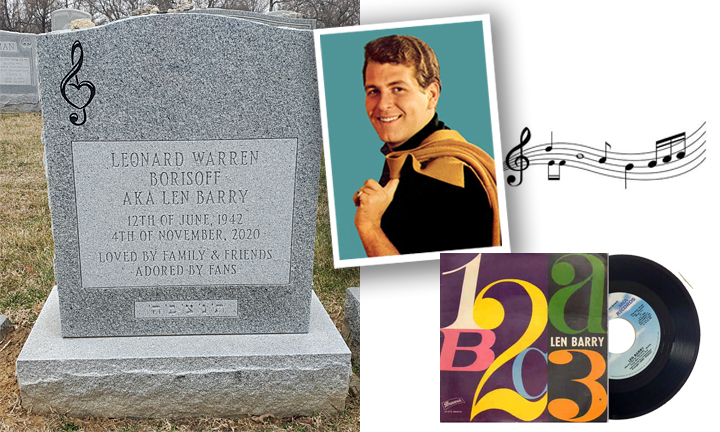

At the far end of Montefiore is the grave of Len Barry.

The former Leonard Borisoff had no plans for a career in show business. As a Philadelphia high-schooler, he had dreams of becoming a professional basketball player. However, while serving in the military, Len had the opportunity to sing with the US Coast Guard band. He enjoyed it so much, he decided to make that his career (singing, not the Coast Guard.). After his military discharge, Len and some friends formed a doo-wop group called The Dovells. The group had a number of hits including “Hully Gully Baby,” “You Can’t Sit Down”, and the million selling “Bristol Stomp.” Len and his band appeared on American Bandstand, Hullabaloo and even in the film Don’t Knock the Twist. He released his first solo recording in 1965 and hit Number 2 on the Billboard chart later in the year with “1-2-3,” a song he co-wrote. Len had a successful singing career, becoming more popular in England. Later, he concentrated more on writing and producing and in 2008, he ventured into creative writing and wrote a novel.

Closer to the front entrance of Montefiore is the grave of Louis I. Kahn.

Louis Kahn was a respected and innovative architect, known for his stark and monolithic designs. Louis’s designs have been featured all over the world. As a professor at Yale, he designed the school’s art gallery. After joining the staff at the University of Pennsylvania, he designed the school’s medical research facilities as well as the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, Phillips Exeter Academy Library in New Hampshire and churches, synagogues and other buildings in India, Bangladesh and Israel, however, some never saw actual construction. Traveling alone in 1974, Louis Kahn suffered a fatal heart attack in the bathroom at New York’s Penn Station. There is a park in Center City Philadelphia named in Louis’s honor.

Out on Philadelphia’s famous “Main Line,” is Merion Memorial Park. I had briefly visited Merion Memorial Park over a dozen years ago. As I drove through the narrow entrance gate, I was intimidated by a large sign announcing that photography was strictly prohibited. I drove in and made a hasty U-turn, cutting my grave-seeking activities short. My return visit still filled me with a bit of trepidation, as their website still carries the same warning about photographs. I slowly breached the entrance and parked my car a little past the cemetery office. I wandered around a bit, trying to locate a particular grave, but the GPS app on my phone was not cooperating. And it was cold. I was about to head back to my car, when a gentleman wearing a coat heavier than mine and carrying a cardboard tray of steaming coffee greeted me with a very friendly “Good morning!” I returned the greeting with a smile. He then asked if there was something with which he could offer some assistance. I hesitated at first. I don’t like to reveal my mission to employees at cemeteries. Not all cemeteries welcome guys like me who are there to visit graves of non-relatives and perhaps snap a few pictures. Also, being fully aware of their posted photography policy, I was not comfortable with giving any information before I could get a proper assessment of this guy. Then, I thought “Eh… what the heck!” I spoke right up and explained that I was looking for the grave of James Bland. He smiled and said “Sure! I can even take you to it. Just give me a minute.” I offered a little wave of thanks and he walked up to the office door and went inside. I paced around in a little circle, trying to figure out how to react when he came back to throw me out.

Out on Philadelphia’s famous “Main Line,” is Merion Memorial Park. I had briefly visited Merion Memorial Park over a dozen years ago. As I drove through the narrow entrance gate, I was intimidated by a large sign announcing that photography was strictly prohibited. I drove in and made a hasty U-turn, cutting my grave-seeking activities short. My return visit still filled me with a bit of trepidation, as their website still carries the same warning about photographs. I slowly breached the entrance and parked my car a little past the cemetery office. I wandered around a bit, trying to locate a particular grave, but the GPS app on my phone was not cooperating. And it was cold. I was about to head back to my car, when a gentleman wearing a coat heavier than mine and carrying a cardboard tray of steaming coffee greeted me with a very friendly “Good morning!” I returned the greeting with a smile. He then asked if there was something with which he could offer some assistance. I hesitated at first. I don’t like to reveal my mission to employees at cemeteries. Not all cemeteries welcome guys like me who are there to visit graves of non-relatives and perhaps snap a few pictures. Also, being fully aware of their posted photography policy, I was not comfortable with giving any information before I could get a proper assessment of this guy. Then, I thought “Eh… what the heck!” I spoke right up and explained that I was looking for the grave of James Bland. He smiled and said “Sure! I can even take you to it. Just give me a minute.” I offered a little wave of thanks and he walked up to the office door and went inside. I paced around in a little circle, trying to figure out how to react when he came back to throw me out.

He returned, sans coffee, but with a small color brochure about the cemetery. “Here,” he said as he handed the booklet to me, “this has some information you may be interested in.” He instructed me to follow him as we traversed the uneven ground of the “Catto” section of Merion. My guide offered a warm “hello” to a fellow poised in front of a nearby grave as we made our way down to our destination. I followed him about midway down a row where he stopped beside a large, but unfortunately cracked, stone slab that marked the grave of James Bland.

James Bland was a musician, songwriter and performer, widely considered to be the first popular African-American composer in the United States. It is estimated that, in his lifetime, James composed well over 600 songs, although only about fifty were published under his name. James wrote “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,” which served as Virginia’s state song from 1940 until 1997, when its lyrics were reconsidered as being racially problematic. He also wrote “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers,” which is the unofficial theme song of the annual Philadelphia Mummers Parade. He gave command performances for Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales. Music historians credit James with breaking down the barriers [for African-American composers] to white music publishers’ offices. He died from tuberculosis — in veritable obscurity — at the age of 57. His grave remained unmarked for 25 years, until efforts initiated by ASCAP and a Philadelphia-based music magazine erected a monument on the plot. Over the years, various music scholarships have been named in James’s memory.

I thanked my guide (who identified himself as the director of the cemetery and graciously allowed me to take photographs) and headed off on my own to locate the next grave on my list. Again, the GPS coordinates failed me and I was left to wander aimlessly. After walking up and down and up and down the vast expanse of the lower “Montgomery” section, I literally stumbled upon the grave of Nehemiah “Skip” James.

Skip James was a singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, best known for his eerie, otherworldly songs featuring his open-tuned guitar and jarring falsetto vocals. Skip played traditional Delta blues with a decidedly dark, somewhat evil, tone. His work, primarily released during the Depression, sold poorly and Skip faded into obscurity. In the 60s, with the help and interest of blues guitarist John Fahey, Skip enjoyed a rebirth of his career. He played folk festivals and toured the country. He has been hailed as “one of the seminal figures of the blues.” 32 years after his death, Skip’s signature song “Devil Got My Woman” was featured prominently in the film Ghost World where it mesmerized the character of Enid, as played by Thora Birch. James’s wife, Lorenzo, who was the niece of legendary blues guitarist Mississippi John Hurt is buried here as well.

On my way out, I serendipitously passed the curbside grave of Jimmy Smith.

Jimmy Smith, as his headstone inscription boldly claims, was the “World’s Greatest Jazz Organist.” He popularized the Hammond B-3 organ and created a unifying link between jazz and the soul sound of the 60s. Cited as an inspiration and influence by dozens of jazz keyboardists, Jimmy was also a guiding force for rock keyboard players like Jon Lord, Keith Emerson and Brian Auger. Jimmy is sometimes called the “Father of Acid Jazz,” for his improvisational style. He continued to record and perform until his death in 2005 at the age of 76.

One grave at one cemetery. Two graves at the second cemetery. Three graves at the third. Clever, huh?

* * * * *